Annie Rainsong knew that today she would die.

And that she deserved to.

She never should have left her vision site, but she was cold, restless, bored, hungry, and ready to be done with this outdoor stuff. She wanted a beer and a cigarette, or at least a shower and a sandwich. No, two sandwiches. She knew she should have been back at base camp by now. Leaving her vision site had been a bad, bad idea. The stupid piles of rocks that marked the trail blended into the darkness now. Nothing looked familiar—or everything looked like something she had seen before. Nothing looked safe. Her head ached; her feet hurt from the ugly new hiking boots. She wanted to stop moving, be done with this. Her shimásání had always told her not to complain, only to be grateful. She pictured her grandmother’s face and remembered the warm smell of the blue corn cakes she fixed for breakfast. It made her feel like crying, so Annie swore out loud instead.

She saw what looked like a cave up ahead and directed the weak beam of her flashlight into the lava. She would climb there, she decided, and hope there weren’t any dead bugs or bat poop to creep her out. The old ones had lived in caves, hadn’t they? Maybe she’d be lucky enough to fall asleep and die. She’d heard of that happening.

Nothing looked familiar—or everything looked like something she had seen before. Nothing looked safe. She hiked toward it, relieved to have a destination even though the blister on the back of her left heel rubbed against the stiff boot every time she took a step. She felt less lost now. Maybe it would even be warmer in there. Mr. Cruz and Mrs. Cooper had told her to stay out of caves, because of hibernating bats and because the caves might have been used by the old ones and contain bones or gifts for the dead. She decided it didn’t matter now. This whole stinking program was a farce, and she was as good as dead anyway.

When she got to the cave, she’d take the boots off. Who cared what Mr. Cruz said? He was a jerk. She never believed in this vision stuff anyway, but she played along. It was better than being on probation for a year and all the bull that went with that. At least, that’s what she’d thought when she let her mother talk her into participating.

As she limped closer, she realized that there were big lava boulders around the mouth of the cave, making it hard to see at this angle. She was lucky she’d found it. Lucky? Cooper said the experience out here changed people, but if it actually gave her some luck, she’d be amazed. She started to climb, struggling against the angle of the hillside, slipping on patches of icy snow she hadn’t seen in the cloud-covered night. Before she reached the top she was practically crawling, using numb fingers to help pull herself to the cave.

Annie made it to the crest of the slope and straightened up, catching her breath.

She remembered the pack-rat nest she’d seen at Grandma’s place, out past the hogan, when life was better, before her shimásání died and her brother had his accident and everything changed. Would the cave be a good place for a pack rat? Or for shash, a bear snoozing off her fall fat and waiting to emerge in the spring, maybe with some cubs? She didn’t like the idea of disturbing a sleeping bear.

The flashlight’s beam reflected off the black rocks at the cave’s mouth and illuminated wavy white lines and stick figures, before the beam disappeared into the darkness. The figures made her think of something a little kid would draw, simple light marks on the dark stone. Mrs. Cooper had mentioned that they might see something like this and told the girls not to touch them.

Annie ran her finger over a spiral. The image captured the moon’s milky light. Cool, she thought. The pictures looked like something her brother might make. She could hear Mother telling him not to draw on the walls; maybe this little brat’s mom told him the same thing.

She wasn’t even hungry or thirsty anymore. Only bone-cold and scared and ready to die. To get the flashlight to shine inside the cave, she had to sink to her knees. The tremor in her hand made the faint beam dance against the blackness. She inched her way toward the entrance, the light preceding her like bad news. She saw nothing threatening. The light bounced off her wrist, and Annie Rainsong glanced at her forbidden tattoo, the skull her mother hated. She’d always thought it was cool, but now she looked away and used her light to search the cave, finding no rats or rat’s nests or anything that looked bearlike. She sat on the rock ledge at the entrance of the cave, put down her flashlight, pulled up the collar on her jacket, and shoved her hands in the pockets. She wasn’t even hungry or thirsty anymore. Only bone-cold and scared and ready to die. Maybe there was a bear in the very back of the cave, where her light didn’t go. Maybe the bear would find her and eat her or feed her to the cubs. That would be all right, she thought. Better than having her own mom yell at her for being a screwup. Better than having Mrs. Cooper tell her she’d messed up the whole trip for the group by not following the rules. Everyone cared about the rules. Nobody cared about her. The cave would be a hard place for Mr. Cruz to find her, but it would be a safe place to die. She was glad those big rocks blocked most of the entrance. They would keep animals out, unless something was already inside; the cave smelled funny. She didn’t like the thought of a coyote finding her. It was bad enough when she heard them howling, and she remembered that time when she was little and she and Grandmother had come across the sheep—or what was left of it—that the coyotes had just killed.

Annie started to relax. The cave was safer than that stupid flimsy tent they gave her. She was OK here, she told herself. She heard the sound of her own breathing and the beat of her heart pushing blood up to her ears. She leaned back, feeling the cold stone wall through her coat, staying close to the entrance. It bothered her that she couldn’t see what was beyond the beam of her flashlight, but be- ing outside bothered her even more. She would wait for the sunrise and as soon as it got light she’d start to yell for Mr. Cruz or go back to hiking, watching for those stupid towers of rocks, the Karens or something, to find the dumb campsite.

Annie Rainsong took pride in her toughness. Nobody in school, when she went to school, messed with her. Teachers left her alone except for some bilagáana do-gooders. If any adults looked at her with pity because of her brother, she gave them a hard glare that said Hands off! She’d sit in the cave and wait for a vision, or wait to die. Who cared about a stupid vision, anyway? She could make that up if she had to.

December’s cold had seeped up through the little bones of her smallest toes all the way to her knees, her spine, and the very top of her head. She readjusted her back against the sharp lava. It wouldn’t be so bad to die out here, she thought. Kind of peaceful. She stretched her legs into the darkness. She had seen on TV that the cold made people sleepy, and then they died. Hydrophobia or something. She wouldn’t mind that. Her mom would start to cry and beg forgive- ness. Too late. Her chindi would hang about and bug her. Maybe they would leave her in the cave, wall up her body until it became a pile of bones. Or not find her at all. Then Mom would be really teed off.

Annie stretched a little more. Her right foot encountered something hard, probably a rock. She adjusted her position, wishing she’d brought her sleeping bag instead of leaving it in the tent. Even with the cold, she felt better here, out of the wind, without the noise of the tent straps and fabric flapping. She saw the sliver of a moon as it rose over a river of darkness separating the clouds. It was hai, winter, and the month of níłch’itsoh, a time when some creatures would rest and others would die. Either way, she thought, it’s how my story plays out.

She must have closed her eyes, because when she opened them again the sky wore a tinge of pink. She remembered where she was and why in the next millisecond. On the next breath, she realized that her back and hips hurt, her stomach ached, and December’s cold had seeped up through the little bones of her smallest toes all the way to her knees, her spine, and the very top of her head. Ever her hair was freezing cold. She shifted and wiggled her feet, glad that she had left her boots on because her stiff fingers would not have been able to deal with shoelaces.

She pushed herself to sitting and glanced down to see what she had pressed against in the dark.

Her screams echoed off the lava.

__________________________________

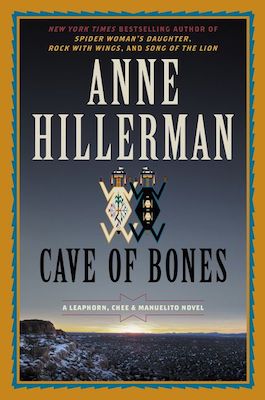

From Cave of Bones. Used with the permission of the publisher, Harper. Copyright © 2018 by Anne Hillerman.

Previous Article

CrimeReads Brief: Week of April 5, 2018Next Article

Why Comedy Is the MostSubversive Art