LR Dorn is the pen name for Suzanne Dunn and Matt Dorff. Their debut novel, THE ANATOMY OF DESIRE (May 11), is a modern reimagining of Theodore Dreiser’s 1925 classic, An American Tragedy.

___________________________________

“Girl Drowned; Escort Missing.” This headline, on the front page of The Syracuse Herald’s July 13, 1906 edition, launched a crime story that still reverberates in popular American culture. The body of Grace Brown, a twenty-year-old factory worker from upstate New York, was recovered from the waters of Big Moose Lake, a fashionable boating spot in the Adirondacks. The cause of death was drowning, but cuts and bruises were found. In 1908n her face and head, indicating she’d been beaten before falling into the lake. During the post-mortem examination, the county coroner discovered something else: Grace Brown was four months pregnant.

So began a murder case that would come to national attention, as well as to the attention of a thirty-four-year-old debut novelist named Theodore Dreiser.

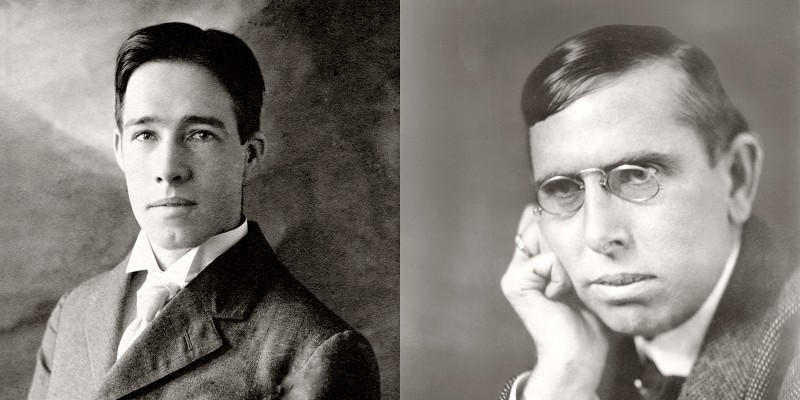

A suspect was identified and arrested. Period photos of Chester Gillette, the accused, show a handsome face that appears entirely modern by current media standards—minus the wing-tipped shirt collar. Thick dark hair, confident gaze, high cheekbones, sensuous lips, a perfectly placed chin dimple, Gillette looks like he could play the heartthrob in a new Netflix series. A hundred years ago, he was known to be a young man on the rise. His uncle owned the Gillette Skirt Company in Cortland, and Chester was working his way up the managerial ranks, heading swiftly toward an executive position and all the perks that came with it.

One of the female workers under Chester Gillette’s supervision was Grace Brown, a local farm girl. In contrast, her photos show a distant Victorian era charm, with little of Gillette’s contemporary appeal. Gillette embarked on a romantic relationship with his employee, and it doesn’t take a lot to imagine their one-sided workplace power dynamic. Gillette was a “catch,” and used his position to bed young Grace and leverage her into keeping their affair a secret. Then, in the spring of 1906, Grace got pregnant. Having no intention of marrying “beneath” him, and fearing a scandal would upset his economic and romantic prospects (he was already courting a beautiful socialite from a wealthy family), Gillette decided the best way to solve his problem was to kill Grace and make it look like an accident.

A man murders a woman who stands in his way of social and material advancement. This was a story that intrigued novelist Dreiser as a real-life case exemplifying the dark side of the American dream. Its themes included economic inequality, the spiritual cost of materialism, the raw desire for social status and financial success. Seventeen years after Chester Gillette was executed in the electric chair following his murder conviction, Dreiser published what many consider his defining work, An American Tragedy (1925).

As Thomas P. Riggio points out in his contribution to The Cambridge Companion to Theodore Dreiser, Dreiser’s fictionalized version of the Chester Gillette murder case “benefitted from the popular interest in criminal biography, a form to which Dreiser’s masterpiece gave new life as the progenitor of documentary novels of crime such as Richard Wright’s Native Son, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song.” It turns out that Truman Capote did not invent the “nonfiction novel.” Forty years earlier, Dreiser used the framework of a shocking crime and murder trial to construct a vast narrative study of the societal and economic forces that shape a such a criminal. As Capote probed the heart and mind of Perry Smith, Dreiser went inside the heart and mind of Clyde Griffiths (he kept Chester Gillette’s initials for his made-up twin) to trace the psychological journey that transforms a relatively average person into a cold-blooded killer. And there stands the narrative formula that seems to underlie much of our ubiquitous and ongoing fascination with True Crime.

***

In preparing to write his novel, Dreiser researched at least two other sensational true crime cases of the early 20th Century, the Harry K. Thaw murder of Stanford White, and the Roland Molineux poisoning murder. Both cases were turned into media circuses by the New York press and became front page news across the country. Both defendants in those cases were high-born Americans, Thaw the son of a railroad baron, and Molineux the son of a distinguished Civil War general who made a fortune in the chemical dye business. Chester Gillette, on the other hand, was born to traveling Christian missionaries who had renounced material possessions in favor of living a life of poverty modeled after Jesus Chris, their Lord and Savior. Conversely (perhaps perversely), the young Gillette yearned for the worldly comforts afforded by financial success. When a wealthy uncle offered him a job at his clothing manufacturing plant, the twenty-two-year-old jumped at the chance.

___________________________________

___________________________________

Here was a “low-born” man, his early life dominated by religious fanaticism, whose circumstances seemed to mirror a majority of Americans at the time. Unlike Harry Thaw and Roland Molineux, Chester Gillette was a relatable and recognizable figure, the industrious striver working his way up in the land economic opportunity. He was the real life equivalent of the hero in a Horatio Alger story, the rags-to-riches archetype that set an example for the rest of the country, proving that the American dream was attainable.

Dreiser found in Gillette the personification of the American dream gone wrong. Seventy years after An American Tragedy’s publication, this theme would be embodied in another success story inverted by a shocking act of violence, the O.J. Simpson murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown. Gillette was neither famous or rich when he committed his act of violence, yet it was his desire for those things that drove him to destroy what he perceived as an obstacle to their attainment.

In today’s true crime docuseries and podcasts, one sees narrative techniques that echo Dreiser’s famed literary naturalism through the juxtaposition of talking heads and straightforward re-creations. These techniques inspired us to take An American Tragedy and the true crime on which it was based, and reimagine them as a crime story for our present moment. Employing the conceit of a transcript-style novel that draws its raw material from interviews, trial testimony, recorded phone calls, social media posts, and email correspondence, we sought to create a form of digital-age naturalism presented from multiple character perspectives. Our Claire Griffith shares initials with Chester Gillette and Clyde Griffiths, yet we changed her gender because today’s symbol for the American dream gone wrong is just as likely to be a female. Social media overflows with people of modest means striving for material success. Presently, that success is measured as much in the number of Instagram followers and YouTube channel subscribers as it is in the traditional trappings of affluence. Which would you rather have, a brand-new car or a million more social media followers? Many of today’s influencers would likely choose the latter. Here’s another one: Would you kill someone for a million more followers? It’s a question that may well have intrigued Theodore Dreiser.

*