For many of us, life right now feels caught up in the ultimate paradox—it appears that many of us have a lot of free-seeming time to do things, but very little motivation to really do anything, at all. And that’s okay. Should I be working on my doctoral dissertation right now? Leave me alone. (Actually no, please come back.)

But if you do want something to do (maybe even cross something off your list), consider diving into a classic detective series. I’m talking really famous, really clever stories. The heavies. The fun stuff. We’ve rounded up a list of the big ones for you.

The rules: we’re keeping this list to mystery series first written during the late nineteenth century through the first half of the twentieth. More modern detective series of note will have their own CrimeReads listicle one of these days, so those of you concerned about where Adam Dalgliesh, Kinsey Millhone, Henry Tibbett, and V.I. Warshawski are, keep your shirts on. Now, this is a transcontinental assemblage, from gentleman amateurs to hardboiled PIs. The only other rules are that there have to be a ton of books in the series, and that they all follow a single detective character. Sounds easy enough. Let’s get cracking.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories

There are fifty-six short stories and four novels in the Sherlock Holmes canon. Arthur Conan Doyle didn’t want there to be that many. He tried to kill Holmes off after “The Final Problem,” in 1893. That’s only twenty-four stories and two novels in. Because fans were so militantly despondent for years afterwards, Conan Doyle had to revive Holmes, first by writing the novel The Hound of the Baskervilles (which is a flashback) in 1901, and then by bringing the detective back to life for real in 1903. The short stories are published in five volumes (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, the Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, the Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow, and the Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes.) Go and read them, and make his whole ordeal worth it. It’s elementary, if you ask me.

Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot series

Agatha Christie’s suave Belgian detective (who appeared in her first novel ever, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in 1920) starred in thirty-three novels, fifty-one short stories, and two plays. That’s so many things. That’s so many things to read. You can find Christie’s short stories anthologized in this collection, or read them in their original volumes, all listed here. Now’s the time to begin reading them. The little grey cells in your head will be very glad you did.

Dorothy L. Sayer’s Lord Peter Wimsey series

Dorothy L. Sayers’s shell-shocked war veteran and bored gentleman sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey was first introduced in the novel Whose Body? in 1923, but went on to solve many more mysteries in eleven novels and twenty-one short stories (anthologized in four collections, and later in one giant one). Aided by his butler, Bunter, his friend Charles Parker, and eventually the clever writer-sleuth Harriet Vane, the Medieval book collector Wimsey’s amateur detective work is often completed to the frustration of the police, including the jealous Inspector Sugg. Though she lived for more than a decade afterwards, Sayers completed the series in 1942, firmly keeping Wimsey’s legacy in the interwar aesthetic. Pay him a call, and stay for twenty years’ worth of mysteries. Cheerio.

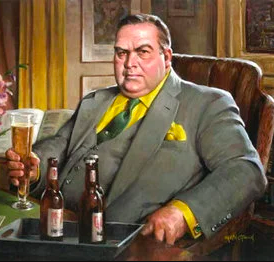

Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe series

Nero Wolfe is a model for these fraught times. A corpulent, wealthy Montenegrin, Wolfe hates leaving his home, which is an elegant brownstone on Manhattan’s W. 35th St (back when midtown wasn’t a festering hellhole—you know what I mean if you’ve ever been to the Port Authority, but anyway). He likes to spend his time reading his books, tending to his temperamental plants, and, an epicurean, eating impeccable meals prepared by his personal chef. His curse is that he’s a brilliant detective, and while he’s able to solve many of the cases from the comforts of his armchair, he sometimes needs his assistant, the spiffy ladies’ man Archie Goodwin, to do the legwork for him. Written by Rex Stout, their adventures total thirty-three books and forty-one short stories. You can find them all in order here. Now be like Nero and stay the hell inside!

Dashiell Hammett’s The Continental Op series

Dashiell Hammett’s other super famous detective (besides Nick Charles and Sam Spade) is a PI for the Continental Detective Agency in San Francisco. We never learn his real name; he’s just known as the Continental Op. He’s unsympathetic, but not totally because he is afraid of not having any sympathy (there’s the tell), but he’s also a little bit ruthless and plenty deceitful. He roams the seedy city streets catching bad guys in thirty-six stories, which you can find listed here, but you probably know him best from the novel Red Harvest, which is actually not a novel at all, but a collection of four out of thirty-six of those stories. Tricky. Read him, hire him, but maybe don’t trust him. Too much.

Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion series

Albert Campion, a Golden Age sleuth created by Margery Allingham, appears in eighteen novels and and fifty-six short stories. One of the four Queens of crime fiction (with Christie, Sayers, and Marsh), Allingham passed away leaving a manuscript unfinished. Her husband finished it, and wrote two more. More than simply a gentleman, Campion is aristocratic. Campion, whose inaugural story appeared in 1929, is pale, bespectacled, and doesn’t have smart-looking face, though he is quite helpful. He also has a pet bird, which he has named Autolycus, and that’s how you know he’s a little bit weird. But when he gets going on a mystery, there’s really no stopping him. His stories are collated here.

Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple series

Miss Marple is the last person you’d want to deal with right now, in the midst of global quarantine, because she keeps popping over and sticking her nose in people’s business, and this seems excessively unhealthy and potentially dangerous. Agatha Christie’s elderly sleuth, an old single women living in the village of St. Mary Mead, is a brilliant but unassuming detective. And she delightfully upends a longstanding cliché: that of the nosy, unmarried, elderly woman. Apocryphally speaking, Christie is said to have created Miss Marple in a 1926 short story called “The Tuesday Night Club,” after a stage adaptation of the 1926 Poirot novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd replaced the spinster character with a young woman, and Christie wanted to vindicate the demographic. Hurrah! Miss Marple appears in twelve novels and six short story collections, all of which you can find here.

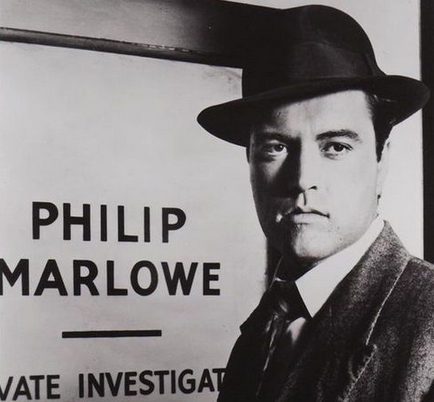

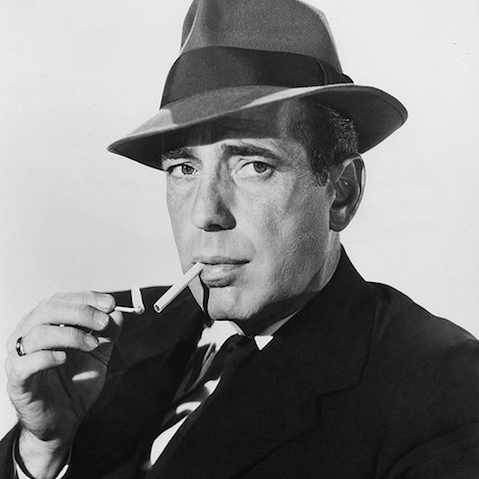

Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe series

Yeah, that’s Powers Boothe as hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe instead of Humphrey Bogart. I’m mixing things up. Besides there being many onscreen Marlowes (including James Garner and Elliot Gould), it’s difficult to count how many of Raymond Chandler’s stories Marlowe is truly in, because Chandler later rewrote twenty-one of his pre-Marlowe short stories and one of his post-Marlowe stories to include him, instead of the undeveloped PI stand-in he had originally written. Without these revisions, Marlowe is the lead in seven novels, one short story collection, and one unfinished novel, beginning with the Los Angles-set The Big Sleep, published in 1939. I’d start there and work your way back, and then head to the doctored shorts. Or read them in whatever order you want, as long as you do it from inside your house. In other words, “Just keep your nose clean and everything will be jake.” Literally.

Nicholas Blake’s Nigel Strangeways series

Poet Cecil Day-Lewis (Daniel’s dad) created the gentleman sleuth Nigel Strangeways under the pen-name Nicholas Blake in 1935 because he needed the cash to support his young family, and his other job was being a poet. But he continued writing them until 1966, even after he became Poet Laureate of the UK. There are sixteen novels (many with inventive titles like Malice in Wonderland, ha!), and you can find them all listed here. There are no photos or illustrations of Nigel Strangeways available, so I’m using a photo of the poet W.H. Auden, on whom the character was ostensibly based. Besides, wouldn’t you like W.H. Auden to have been a detective protagonist? “The glacier knocks in the cupboard/The desert sighs in the bed/And the crack in the tea-cup opens/A lane to the land of the dead.” Those lines could really all pass as titles. His thoughtful detective series writes itself. Writes itself.

Ngaio Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn series

The creation of New Zealand Golden Age writer Ngaio Marsh, Roderick Alleyn is a crime-solving gentleman detective, but unlike many others who share this general archetype, he’s also a police officer, himself. He’s CID at Scotland Yard. Well done, old boy. First appearing in 1934, Marsh published thirty-two novels about her detective, through the 1980s. And here they are!

Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer series

Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer, another SoCal private eye, starts out hardboiled like all the rest, but grows progressively more empathetic and thoughtful. Appearing in eighteen novels and nine short stories from 1949 to 1976, Archer works on crimes and deaths that impact regular (often suburban) life. He doesn’t reveal much about himself, but you should try to learn about him anyway. Paul Newman played him in the film adaptation, but they renamed him “Harper.” But who cares, because… Paul Newman.

S.S. Van Dine’s Philo Vance series

Created by S.S. Van Dine (who also “narrates” these stories) Philo Vance is a handsome, urbane, dandyish detective. He, a stylish sybarite and a Renaissance man in a real upper-class sorta way (he breeds dogs and does archery and plays golf) appears in twelve novels. Written from 1926 to 1939, Vance is a compelling lead. He’s quite sarcastic and even a little cold, but if you want to tag along as he cleverly solves a murder (or twelve), you won’t be disappointed.

Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade stories

I’m sad to say that Dashiell Hammett didn’t write any more Sam Spade novels after The Maltese Falcon (1930), but there are four short stories that follow, one of which was published posthumously. It’s not exactly a trove of Spade chronicles, so it might not be a dream come true, but maybe it’s the stuff dreams are made of. Who knows.