The release of No Time to Die marks the retirement of Daniel Craig’s James Bond, a man made taciturn and morose due in part to the loss of a great (and complex) love at the end of Casino Royale. As we bid farewell to this self-styled “grumpy” Bond, it’s worth revisiting the other Bond film about a great and lost love, 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. This film is generally viewed as an outlier in the franchise. It gives our playboy agent a plausible, affecting romance—think of it as “The One Where Bond Gets Married”—and features a one-off performance of 007 by Australian actor George Lazenby.

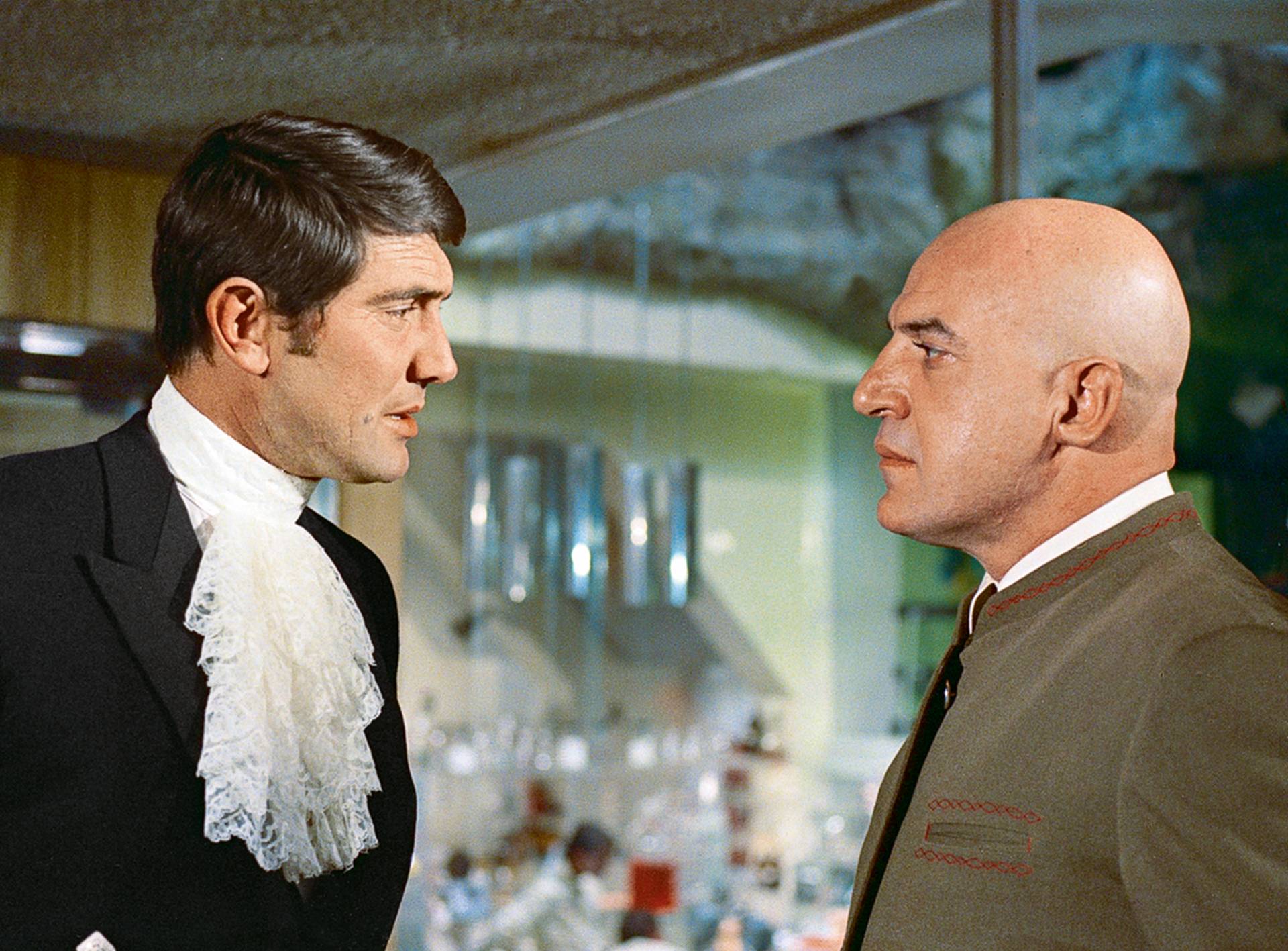

Despite these oddities, I have long maintained that Secret Service is the best Bond Film. This is no bad-faith contrarian take. I’m a long-time Bond fan. I love baroque villainy, elaborate chase scenes, and double entendres over conveniently placed glasses of champagne. Secret Service is not great simply because it breaks format so much (although those breaks are invigorating). Even with its quirks, the film (directed by Peter R. Hunt) elegantly packs in all the elements that make Bond movies great. There’s a returning baddie: Telly Savalas replaces Donald Pleasance as the arch-villain Blofeld, and his well-mannered jolly suavity is low-key chilling. Blofeld’s got an androgynous henchwoman in Irma Bunt (Ilse Steppat), his stern, sporty majordomo. Settings include a bit of local color (Corsican bullfighting!) and a luxe Mediterranean hotel with an azure pool and high-stakes casino. Most of the spycrafting takes place in an Alpine resort, and there is no winter sporting activity (skiing, bobsledding, ice racing) that is not used for an excellent chase scene. In one of the big set pieces, Bond literally outskis an avalanche. In perhaps an even scarier scene, he is cornered into the lift station of a ski gondola, jumping back and forth between moving gears before he makes his final escape by easing his way down the cable, his lengths dangling beneath him. Hunt shoots this scene exquisitely, with lots of hand-held close-ups, menacing angles and heart-thumping cross-cutting. He makes the whole film a visual treat: it’s a testament to how good editing and cinematography can skyrocket your adrenaline just as much as high-tech effects.

Secret Service is so wonderful—and so very Bond—because it delivers all these familiar pleasures with the camp and cheek that are equally vital parts of the franchise.But Secret Service is so wonderful—and so very Bond—because it delivers all these familiar pleasures with the camp and cheek that are equally vital parts of the franchise. Wisely, the film does not try to make Lazenby’s Bond prove himself by perfectly fitting the Connery mold. Instead, it plays boldly with the Bond persona—a kind of winking play with the image and expectations of the character that’s a tart top note for much of the universe. Secret Service also does inspired stuff with the archetype of the Bond Girl, introducing the exceptional and unforgettable Countess Teresa di Vincenzo (known as Tracy, and played by Diana Rigg.) She makes the typical Bond Girl subplot both sizzling and romantic, leading to a real emotional wallop. Secret Service is one of those rare treasures of genre fiction, one that manages to be a witty send-up of its norms while remaining a great example of the thing itself.

The film makes the ballsy decision to teasingly put off revealing its new Bond. We only see the back of his head as he speeds down a curving Mediterranean seaside road.

Before we see his face, we see Tracy’s in his rear-view mirror as she overtakes him on a hairpin turn. An intrigued Bond follows her to the beach. To get a better view of her, he stares at her through a scope. This framing evokes that trademark button that introduces Bond before the opening credits; it positions her at Bond’s level, as his compatriot. At the moment, however, this compatriot seems intent on flinging herself into the sea (in a sequined caftan, naturally). Bond’s attempts to save her are stopped by some violent thugs, and Tracy speeds off again, leaving Bond with only her slippers, Cinderella-style.

Tracy and Bond finally meet properly at the hotel, and here’s where we truly see how the pair of them can go toe-to-toe. Tracy’s a poor-little-rich-girl with a death wish, a clichéd backstory that Rigg imbues with wounded passion and fiery pride beneath her porcelain exterior. Despite her baggage, in the inevitable Bond—Bond Girl seduction, she is no easy conquest, and matches him beat for provocative beat. She gazes at him with the same bald sexual appraisal with which Bond usually looks at his “girls.” It is she who propositions Bond—“I hope it will be worth it,” she says, with cool bemusement, as she hands him her room key. She initiates their sexual encounter, and she’s the one who flies in the night afterwards, leaving Bond pleasantly intrigued.

It’s in his chemistry with Rigg, and in selling Bond’s more romantic side, that Lazenby’s portrayal of 007 is at is strongest. He was certainly cast in part because of a ballpark resemblance to Sean Connery (not to mention a chin dimple to rival Cary Grant’s). And he sells the action and the suavity well enough, even if there are some accent slips and the very English Bond sounds unforgivably Aussie. It’s mostly a good thing, though, that Lazenby wears the role lightly. Like most Bonds, he enjoys the perks of the gig, but he does so with more affable warmth than the cool unflappability of other Bonds. Because he takes himself less seriously, he takes genuine pleasure in being bested by a woman. (“This never happened to the other fellow,” he quips as Tracy escapes in her sports car, anticipating any criticism that he can’t fill Connery’s shoes.) He looks at Tracy not just with COMPETITION and desire, but with a tender and perceptive eye to her vulnerability that makes his eventual commitment to her more plausible. He may not be in the running for best Bond, but he’s the best Bond for this story.

He may not be in the running for best Bond, but he’s the best Bond for this story.Perhaps because of this depth of his attraction to Tracy, Bond’s not too miffed to discover that he’s not in a spy plot at all, but rather a marriage plot worthy of a Regency Romance. The henchmen following Tracy are actually trying to protect her—they work for her father, a well-connected Corsican gangster. He’s decided that Bond can cure what ails Tracy, and suggests that they marry. When Bond can’t be bought with money, Tracy’s father offers him a lead on the whereabouts of his old nemesis Blofeld. Bond is tempted, but Tracy gets wind of her father’s scheme, she makes her dad cough up the intel without any promise of marriage. She’s humiliated, but when the gallant Bond convinces her he’s genuinely into her, their sexy Bond-style meet cute transitions to a distinctly un-Bond-like romcom montage: horse riding and kissing in sun-dappled gardens, all set to one of the most poignant of Bond songs, Louis Armstrong’s “We Have All the Time in the World.”

All the time in the world, however, is not a promise that 007 (or a Bond movie) can really make, and the Tracy-Bond romance is put on the back burner while Bond goes after Blofeld. The idea that a 1969-vintage James Bond is only going to sleep with one woman over a whole 2 hours and 28 minutes is inconceivable, but the Bond promiscuity here tends toward the goofy-sexy end of the spectrum (previewing a lot of the Roger Moore films). It elevates the campy genre of 007 hijinks to the level of French bedroom farce, with a ludicrous series of assumed identities and misunderstandings. Blofeld’s plot is grade-A bonkers: he’s got a lab up in the Alps where he’s developing viruses on under the pretext of running an allergy clinic. Reader, you will be shocked to learn that all the patients at this allergy clinic are model-gorgeous women, who are being hypnotized into transmitting these viruses across the world. For this mission, Bond has assumed the identity of genealogist Sir Hilary Bray. (The real Sir Hilary is played briefly by George Baker, who was himself considered for the role of Bond. In another wink at the masquerade that is the Bond persona, when 007 is in the role of Sir Hilary Bray, Lazenby’s voice is dubbed with Baker’s). Bond gives his Sir Hilary some tweedy, effete mannerisms that lead all the women, who can’t help gazing at him with rapt doe eyes, to assume he’s gay. When they inevitably find themselves in his bedroom (to examine his book on heraldry!) he convinces them that they’ve seduced him and brought out his latent bisexuality, calling each one in turn “unusual” and an “inspiration.” While not free of the antiquated sexual politics that are also a trademark of the Bond films, there’s something rather enchanting about the straight-up goofiness of this situation, one that reminds us that seduction in the Bond universe is not always suave savoir-fare, but also a sexiness borne of pure silliness. The whole thing is so smoke-and-mirrors that it gives the audience a of permission structure to get a voyeuristic pleasure out of Bond’s philandering, while reassuring us that it is no real hindrance to his relationship with Tracy.

When Tracy comes back on the scene, coming to rescue Bond from Blofeld’s pursuing henchman (in ice skates and furs no less), the movie really zings back into life. Tracy proves herself more than your standard-issue Bond Girl: she’s his match professionally as well as sexually. Rigg was more prepared than Lazenby to take on a Bond film: she’d just spent three years on the swinging spy series The Avengers, where she played the martial-arts-proficient, polymath secret agent Emma Peel. The lethal Mrs. Peel was no stranger to a Bondian quip. (In one episode, Peel seems to be sent back in time, and is put in a stockade by a Puritan who calls her “a heretic, a bawd, a witch—designed to drive a man to lust.” Her reply: “You should see me in 400 years.”) As Tracy, Riggs brings both Mrs. Peel’s chops and the quips, swirling and swerving as she leads Blofeld’s henchmen on a merry chase onto an ice-racing course. She weaves through the already racing cars with cool nerves and an evident thrill as she narrowly avoids a pile-up that sets the henchman’s car ablaze. (She could probably have gotten them away a lot faster if a besotted Bond wasn’t constantly distracting her by kissing her neck.) After this, when—in a standard romance plot contrivance—Bond and Tracy are trapped together in a barn during a snowstorm, Bond finally realizes he’ll never find another girl like her, and she accepts his proposal.

The course of true love, of course, can’t run that smooth: Tracy is captured by Blofeld, but she pulls out some of Mrs. Peel’s marital arts chops to fend off his oily advances, going after him with a broken bottle and murder in her eyes. Even after Bond saves the day (while narrowly losing his grasp on Blofeld), we know this peace cannot last. Bond’s wife will always be a target, and a married Bond cannot continue to give us the expected pleasures of the franchise. Yet when the just-wed Tracy is gunned down in Bond’s passenger seat (the shot resembles the deadly denouement of Bonnie and Clyde), it still sucks the wind out of you. As does Bond’s shell-shocked response: he just holds Tracy in his arms, weeping. When the Bond theme blares up as the credit roll, it feels like a violation.

I first got hooked on the Bond films during Christmas-week marathons as a middle-schooler, and found my way to the Fleming novels from there. To be a teen girl Bond fan was, obviously, an ambivalent experience. I was deeply attracted by the series’ heady mixture of glamour, sex and danger, and its often daring (if often equally interchangeable) women. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was so special to me not only because it gave me so much of the fun stuff I loved about Bond, but it also gave me more: romance, pathos and a space where I could truly imagine myself within it. With its nervy confidence that Bond could keep so many of its elements running on all cylinders, Secret Service made a Bond that was truly reflective of its many pleasures, but also its many fans.