Thinking back on the story of how this book was written, I am reminded of just how powerful a force stubbornness can be. The first time my Dad asked me to help him write his book, I remember saying, (I don’t want to be over-generous in my recollections), “God no.”

But he kept asking, to the point where I started trying to avoid him. The fact that I was still living at home at the time meant this was no small feat.

I was experiencing that malaise which many recent college grads will find relatable. Upon leaving school, I discovered the economy was either less forgiving, or my degree of more dubious merit, than my college advisor had led me to believe. I sent my resume to everyone in Idaho with an email address: family friends, distant relations, acquaintances from the gym— a shotgun approach that, based on the profound lack of response, felt like trying to invest for retirement by dropping change in a wishing well.

Compounding my sense of shame was the fact that my particular English degree (because of course I had an English degree) was from an Ivy League school. I had no idea what this meant, exactly, but still thought other people should find it significant. So it was that I found myself back in my childhood bedroom, going to work at the same job I’d had when I was fifteen years old (lifeguarding at the YMCA) and, between sleep and work and trying to avoid running into anybody who might recognize me, I was also getting cornered at the kitchen table by my Dad, who wanted help writing a historical fiction novel about orchid hunters.

One thing I know about my Dad: Kevin McNeill loves to tell stories, to anyone who will listen. He always wanted to be a writer—being a father, not so much, he liked to say to me and my brother, usually at breakfast. The fact that he turned out to be a dedicated father and devoted husband could be viewed as quirks of an otherwise faithful writer. With his two sons, I like to believe he finally found his (captive) audience.

So why, after so many years of giving his stories away for free, did he finally decide to fob them off on the entire world? Well, you have my Mom to thank for that.

I know, I know, we haven’t even gotten to writing the book yet and I’m still introducing more characters. But Sheila McNeill is the heart—of this story, and ours. It would be impossible to explain either without telling you who she was.

Sheila grew up on a dairy farm in Ireland, as one of twelve children who formed their own secret world between them. At school, she was elected Head Girl and given a room to herself (which she in turn gave to any girl who wanted to sneak a cigarette). She tried out for the role of old crone in the school play, because it looked like more fun than the lead. She watched airplanes cross the sky and dreamed of traveling. When she graduated from Nursing College she got her chance, leaving home to work in Bangladesh for an aid organization, before moving to Israel. That was where she met Kevin.

I wish the whole world had gotten the chance to know my Mom. This is partly because she was very pleasant company to be around, but mostly to save me the trouble of having to say that out loud. It’s easier if you already knew her, to save me from explaining this, which is impossible to explain.

She hated being called “sick,” as if that meant she should drape herself in blankets and retire to a four-poster bed, where she could smile weakly and drink broth for the rest of her life. She took her illness and moved it so far outside of herself that it appeared to us like something tiny in the distance. That was her gift. That might have been why, on a vacation to the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, she suggested to my Dad that he be the one to write a book about the orchid hunters they learned about, who had traveled into dangerous territories and returned with something common, which somehow became a treasure when it was transplanted thousands of miles from home.

So I, being the hero of this story, if you remember, got over myself (heroically) and agreed to help my Dad write his book. Dad wrote, I edited, and Mom listened—but of the three of us, her part was the most important. As far as I could tell, our story was only working if she was laughing. You could see her spirits liS when she heard her suggestions take shape on the page. She was our only reader, and she had only one rule: it had to be fun.

We wanted our story to transport the reader to a different time and place, to immerse them in a thrilling adventure. Such writing might be called ‘escapist,’ perhaps disparagingly (perhaps charitably!), with the implied criticism that those who read such things are interested only in running away from the problems of their daily lives. But I don’t think that’s right. I think when we read this genre, or any genre, our goal is not to escape from the world, but to escape to ourselves, and return to the source of our fears and dreams. The demon we cannot confront in reality—either because it is too large or too much a part of us—is given a name in genre, and summoned to the page. If we are ready, we may face it there, and see ourselves. There is nothing comforting or safe about genre.

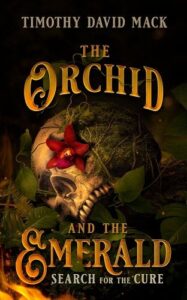

The hero of our story is on a quest for a Holy Grail. The Grail, in this case, is an orchid, a jungle remedy that may be the cure for his daughter. It is the cure his wife did not receive in time, the cure that Sheila insisted was always just about to be discovered.

I am reminded of how powerful a force stubbornness can be. It matters more than intelligence, which doubts itself, or strength, which weakens, or hope, which is lost as easily as it is found.

Sheila was the most stubborn person I’ve ever known. She found a way to carry on, in the memories of those who knew her (which includes you too, now), and in the spirit of this book.

She would have one request, if you decide to sit down and read our story: try and have fun.

***

1/3 of the authors’ royalties will be donated to the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.