Imagine crime fiction without the freedom to explore different perspectives to change point of view. Think of the omniscient voice of the author giving us a distant third-person account of events.

The friends had decided to spend the Whitsun weekend at Goodseaves, one of England’s finest stately homes. Jill and Jane were in the Alderton Room when Jill stabbed Jane through the heart.

The all-knowing, all seeing author perspective that was once fashionable and can be found wholly or intermittently in classics such as The Lord of The Rings by JRR Tolkien makes for a short and unsatisfying crime fiction read. In fact, without shifts in points of view, it’s arguable crime fiction couldn’t exist at all.

The archetypal detective, however brilliant, almost always starts from a position of ignorance. The crime can be shown to the reader, but whether blind to the truth or in on it, the reader’s satisfaction comes from seeing the detective piece together the puzzle, an endeavour that’s hard to portray without the detective’s limited perspective blinding her or him to the secrets of the crime.

Classics such as Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie go further than blinding the detective. Each of the characters has a limitation that gives them an incomplete picture of the truth, and it is by examining the crime through these flawed perspectives that the detective-reader can piece together the truth.

Examples of the unreliable narrator can be found throughout ancient Greek and early western literature, but the technique has been popularised by modern crime fiction. Christie introduced it as a new dimension for her readers in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and it is now a staple of psychological thrillers, a point of view that seems to reveal everything, but which by flaw or defect of the character is untrustworthy. Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn used this to powerful effect, offering a thoroughly engrossing way for readers to puzzle together the truth. The 7 ½ Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle by Stuart Turton serves up a unique take on perspective that plays with the conventions of reliability.

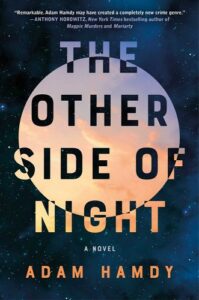

When planning my latest novel, The Other Side of Night, I set myself a number of technical challenges. I knew perspective would play a huge role and spent a great deal of time finding the most interesting way through the story. As it happened, that route involved making use of first-, second-, and third-person as well as journal entries, letters, court reports, past, present and future. For a relatively short book, it is quite dense in terms of the perspectives, and hopefully readers will appreciate the rich experience.

While perspectives can shift to give a different dimension to a story, they should never be used to trick or deceive the reader. I can think of few things less satisfying than an author typing, ‘she knew the true source of danger, but decided not to think about it now,’ or ‘the killer knew his next victim. She would say hello to him every morning, calling him by his name which he couldn’t think about because it broke the line he’d drawn between killer and everyday civilian’.

I’ve seen variations of both forms of forced concealment in published novels, and find it jarring. Good use of perspective will usually conceal something from the reader, but it should never aim to trick or bamboozle by hiding something that would naturally be revealed from that perspective.

When thinking about The Other Side of Night, I reached for some of the books that had made an impression on me because of their brilliant use of perspective.

Moonflower Murders and A Line to Kill by Anthony Horowitz taught me different lessons. Moonflower Murders, the second novel in the Susan Ryeland series, is a Russian doll of a book, with a novel inside a novel, building fiction upon fiction, interlinking stories in a marvellously inventive way. A Line to Kill is the third book in Anthony’s Hawthorne series, and it is ostensibly a classic whodunnit, but Anthony inserts himself as a character in the book, a defining feature of the Hawthorne series, and the fun, self-deprecating portrayal of the author reminded me that there are no rules in fiction and that as authors we are only bound by the limits of our imagination.

Another influential book was Catriona Ward’s The Last House on Needless Street, which plays with perspective in ways that are brilliantly inventive. I learned that readers will trust the author to be as creative and wild as they like provided the perspective feeds the experience and delivers a satisfying payoff.

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell isn’t ostensibly a crime novel, although all the linked stories told in the book involve a crime or mystery. It is a masterclass in the use of perspective to weave a story linked through time and space in a way that keeps giving readers reveal after reveal and a rich stream of emotional payoffs.

Taylor Jenkins Reid uses perspective to great effect in The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, combining the stories of Hollywood icon Evelyn Hugo and magazine reporter Monique Grant to reveal their unique connection.

Creative use of point of view doesn’t have to be a feature of an entire book. In his compelling legal thriller The Devil’s Advocate, Steve Cavanagh uses perspective to build tension in a single brilliantly executed sequence, shifting from one potential victim to the next, until the target is ultimately revealed.

One of my favourite examples of the power of perspective isn’t a crime novel at all, unless one counts the crime of war. Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 builds the horror and madness of war through the clever use of multiple perspectives, playing with time and revealing the key moments in the novel through the experiences of different characters, so the reader understands one truth before realising it was incomplete, and that the whole truth is something else entirely.

Perspective doesn’t have to be multi, broad or temporally disparate. I’ve used single perspective in my other novels and screenwriting to create a sense of mystery and claustrophobia, so the reader feels what it’s like to have the truth tantalisingly out of reach. One of my favourite examples is The Hahnemann Sequela by Harold King, an underrated thriller about an everyman being hunted by elite operatives who want to capture him alive. A tight, restricted perspective can be used to brilliant effect to ratchet up the tension and heap pressure on a character, which all translates into a thrilling experience for the reader.

Ultimately the most important perspective in any novel is that of the reader. Whether one goes for a tight point of view, blinding the protagonist to a mystery or source of danger, or for a multicentric, broad point of view that leaps through time, the job of the author is to figure out the best way to give the reader a satisfying experience, to build an emotional connection between them and the characters, and to ensure the reader ends the book with a feeling of regret they couldn’t inhabit that particular fictional world a little longer.

***

–Featured image: A Bar at the Folies-Bergere,

1882, Édouard Manet