New Zealand / Aotearoa (as it was named by Maori, the first settlers, ‘The Land of the Long White Cloud’). The general perception, encouraged by travel agencies’ websites and brochures, is of a peaceful and beautiful country. Two long islands and a smaller rounded one below; a slightly broken exclamation mark at the bottom of the South Pacific. The adjectives most used are pure, spectacular, unpopulated. And the people? Kiwis (as the approximately five million of us living down here are affectionately nicknamed) are usually described as being friendly, welcoming, easy going.

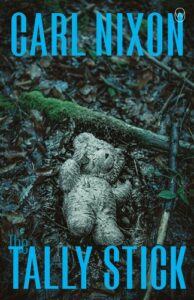

I think that is why many readers, especially those living outside this country, have been shocked by my latest novel, The Tally Stick. The mountainous setting on the West Coast of the South Island, is scenic but inhospitable. More than that actually; it’s immediately deadly for a family visiting from England in 1979. The New Zealander characters are duplicitous and venal. They lie to and manipulate children. The lives they live are close to feral. You may be surprised to learn that The Tally Stick is by no means an outlier in our national literature. The New Zealand literary landscape is full of dark characters and even darker events: physical and emotional isolation, hidden trauma, sudden violence and death. Perhaps there has never been such a gulf between how a nation is perceived and how it is represented in fiction.

The first thing to consider when examining why that might be true is New Zealand’s geographic isolation. We’re a long way not just from anywhere, but from everywhere. New Zealand was the last major landmass on the planet to be colonized by humans. Polynesian settlers, in a feat of magnificent navigation, deliberately sailed south from Polynesia, discovering Aotearoa in approximately 1300. The rest of the world only arrived in numbers after the Englishman Captain James Cook mapped the coastline in 1769. Inevitably the meeting of cultures was traumatic for Maori. European diseases decimated the population. Traditional tribal land was lost through both purchases and skulduggery. Bloody intertribal musket wars were followed by the Land wars of the 1845 -72, which resulted in confiscation of Maori land.

It’s significant that even today there is almost no local fiction that realistically addresses the early colonial period or the clash between Maori and Europeans, apart from a rather ‘Boys’ Own Adventure’ trilogy of novels by Maurice Shadbolt (1932 – 2004), beginning with Season of the Jew (1986). Some academics argue that there’s been a deliberate forgetting of that time by the dominant European culture, a rather guilty looking away. Instead Europeans developed a smug myth of inter-cultural harmony. The dominant culture’s narrative was that Maori were living happy mainly rural lives, content with what they had, and that colonisation had done them far less harm than it had to most Indigenous peoples around the world.

In the early 1970s the first published Maori novelists Witi Ihimaera (who was motivated by the total lack of fiction representing Maori lives) and Patricia Grace, tended on the whole to emphasize the positives of Maori culture. It wasn’t until Alan Duff’s Once Were Warriors (Tandem, 1990) and the internationally acclaimed film adaptation in 1994, that we got an angry and visceral literary depiction of the traumatic impact of colonization on contemporary Maori lives, especially urban Maori. The main characters Jake and Beth Heke lead lives blighted by poverty, alcohol, gang culture, violence and general hopelessness. The book features domestic violence, child neglect, rape, and teenage suicide. Once were Warriors was described in one reviewer as “a kick to the guts of New Zealand’s much vaunted pride in its Maori/Pakeha (European) race relations.” (A related idea was recently expressed (and more succinctly) to the world media by Kiwi film director Taika Waititi when he claimed that New Zealand is “racist as fuck.”) Duff continued mining these themes in a series of dark novels including One Night Out Stealing (1991), Ward of the State (1994) and two sequels to Once Were Warriors.

A more recent novel showing that things have not changed much in the last thirty years for some Maori is the novel Aue by Becky Manawatu, (2019) which was winner of New Zealand’s premier literary prize for fiction, the Jan Medlicott Acorn Prize in 2020. Aue is a cry of lament. That book’s themes are also front and centre in this country’s best known novel, Keri Hulme’s Booker Prize winner, The Bone People (Spiral Collective, 1984). At the time some reviews were critical of Hulme’s detailed descriptions of the domestic violence inflicted on the mute foundling Simon, by his Maori foster father, Joe.

It’s not only the colonial legacy for Maori that has contributed to the dark side of our national literature. In the 1980s I had a lecturer at University, Professor Patrick Evans, who claimed in his typically controversial and amusing manner that New Zealand literature “began in 1882 with the introduction of refrigerated shipping.” His thesis: before 1882 New Zealand was a colonist’s Eden, a pastoral ideal in the Pacific. After 1882, however, we were essentially a country devoted to the raising and mechanised slaughter of sheep and cattle. New Zealanders had blood on their hands. Every Kiwi could lie in bed at night and listen to the silence of the lambs. Patrick had many examples of his ‘slaughterhouse fiction’, including several bloody incidents from the stories of Katherine Mansfield (1888 -1923). His best example (Exhibit A for the prosecution) was the novel Sydney Bridge Upside Down by David Ballantyne (1924 – 1986) first published in 1968, when the book was largely ignored (or derided for being too nasty), but reissued to acclaim in 2010 by Text Publishing. At the heart of that novel is a teenage boy who’s superficially polite and friendly but has the cold heart of a serial killer. Most of the action (and the bloodshed) takes place in an abandoned meat works by the ocean. Another writer who Patrick liked to quote was Ronald Hugh Morrieson (1922 – 1972). Morrieson’s novels feature (in no particular order) lust, murder, necrophilia, drowning, and human immolation. His best known, The Scarecrow (1976) has the opening line, ‘The same week our fowls were stolen, Daphne Moran had her throat cut.’ Darkly brilliant.

There were other national traumas that inevitably appear directly and indirectly in our literary landscape. Because we are a series of islands with many rivers, by the early 20th century, drowning became known throughout the Commonwealth as ‘the New Zealand death’. I can think of several literary drownings off the top of my head. My favourite novel based around a drowning is Kirsty Gunn’s small masterpiece Rain (1994). Maurice Gee’s Going West (1992) is also excellent.

However the greatest national trauma was undoubtedly World War One. From a total population of roughly only a million, New Zealand sent 100, 000 soldiers, mostly young men in their twenties. 18,000 were killed. Another 25,000 returned wounded. None of the bodies of the dead came back – it was too far, too impractical. Drive through any town in the country today and you’ll see stone memorials to the war dead. Often names are repeated; brothers, cousins. The mothers, fathers, sisters, younger brothers – all those who were too young or too old to go – were left with nothing except a few photos and a name carved in cold sandstone or marble in a park or on a nearby hillside. Nearly everyone was affected directly or indirectly.

To make matters worse the soldiers who did return in early 1919 brought back with them a particularly deadly strain of influenza. The ‘Spanish Flu’ cut a wide swath through New Zealand with a far higher mortality rate among the young and previously healthy than Covid 19. New Zealand and small rural communities were hit very hard, Maori hardest of all. 9000 New Zealanders died, most in a two month period. At least this time the bodies were buried close to home.

As with the early colonial land wars there is suspiciously little fiction dealing directly with either World War One, its impact on those who remained or those who fought, or the Spanish Flu. (For fifty years they weren’t even addressed by non-fiction). The cultural attitude was ‘put it behind us’ ‘get on with life’. These overlapping national traumas however, along with the colonial legacy, planted the seed for the strain of fiction which slowly formed over the rest of the twentieth century. Eventually it takes the shape of a recognisable New Zealand literature dominated by themes of physical and emotional isolation, cultural conformity, the repression of dark secrets and urges, and sudden acts of violence and death.

It would require a much lengthier and more detailed article than this to examine all the possible examples. If you’re interested in a deeper dive, I would recommend starting with the short fiction of Frank Sargeson, ‘the father of New Zealand fiction’. Sargeson (1903 -1982) was a gay man in what was a judgmental and sometimes petty and vindictive culture. His characters are often damaged and in some sort of hiding—from themselves as well as others; the stories fizz with the pressure of repressed lust and the danger inherent from ‘normal’ people. The same darkness (and more) can be found in the work of this country’s greatest novelist, Maurice Gee (1931 – ). In a remarkable body of work, for both adults and young adults, Gee made a career out of throwing light on the hypocrisy and darker side of New Zealand’s conformist society and the violence that’s always just below the surface. In the novel Crime Story (1994) a woman is crippled after being pushed down the stairs by a young burglar. In The Fat Man (1995) a petty criminal returns to his hometown to punish his childhood bully—and the bully’s son. Live Bodies (1998) reimagines the true story of a German Jew who fled Germany in the 1930s for New Zealand looking for safety but instead was incarcerated during the war years on a small windswept island in the middle of Wellington harbor alongside Nazis.

As a final insight into the darker side of the New Zealand character I recommend the short fiction of Owen Marshall. His story Coming Home in the Dark has recently been turned into a feature film. As anyone who has seen the movie or read the story will know, the horrifying ordeal faced by an average New Zealand family is the stuff of nightmares. it doesn’t get any darker than that.

Welcome to New Zealand. We hope you enjoy the beautiful scenery. The people are friendly.

***