There’s a familiar routine many of us go through whenever a new story by the writer David Grann comes out: we stop what we’re doing, clear our schedules, screw up our courage, and read the thing from the first page to the last, through every bizarre turn, chilling discovery, and provocative insight—then we get on the phone/email/social media to find out which of our friends have been doing the same these last hours and which can be convinced to undertake it as soon as humanly impossible. That’s how it went earlier this year, when Grann’s latest story, “The White Darkness,” first appeared in the New Yorker, telling the harrowing story of Henry Worsley, the former British special forces officer and devotee of Ernest Shackleton who in 2015 set out in his hero’s footsteps, aiming to cross Antarctica on foot. Worsley was an intensely complicated man, driven by vast reservoirs of will, honor, and something more obscure, impossible to define, something that would drive a man to the most inhospitable terrain on earth, alone, to suffer a long season of darkness and danger with little hope of returning safely, all the while keeping composure and perspective enough to pass along his many insights on what the journey might mean. Although the end result of Worsley’s attempt is now well-known, Grann tells it with masterful suspense and an incredible empathy for his subject and his quest.

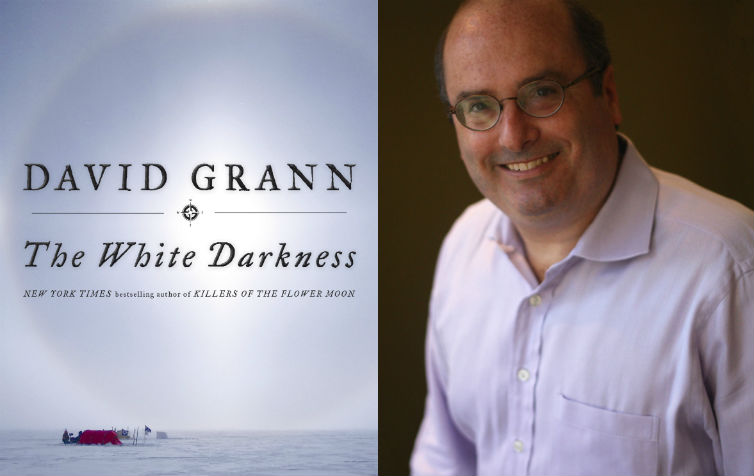

The White Darkness, now released in book form along with the eery photographic remnants of Worsley’s journey, is a story you won’t soon forget, a book you’ll be driven to read more than once over the years. The same goes for much of Grann’s work—Killers of the Flower Moon, The Lost City of Z, The Devil and Sherlock Holmes, or any of the incredible stories he’s reported about crimes, adventures, mysteries, and more. I reached out to him on the release of The White Darkness to discuss Henry Worsley, Antarctic exploration, and what draws Grann to these extreme figures and ultimate mysteries.

Dwyer Murphy: For most of your stories, even exploration stories like The Lost City of Z, you’ve been able to travel to the places you’re writing about. With The White Darkness, that was never really going to be possible—the impossibility was almost the point. How, then, did you get a sense of landscape, not only the details of the Antarctic but how they played on Worsley’s mind and spirit? Reading the story, the terrain feels almost alive.

David Grann: It’s the first time I’ve written about a place that I did not visit, and it took me a long time to wrap my mind around Antarctica. It’s unlike any other place on earth. The continent is nearly five and a half million square miles—larger than Europe—and it doubles in size in winter, when its coastal waters freeze over. It’s the coldest continent, with temperatures sinking to minus seventy degrees Fahrenheit, and the windiest, with gusts at more than a hundred miles per hour. At times, I felt as if I was writing about outer space. Thankfully, many Antarctica explorers have left behind copious diaries and letters, and Worsley, in particular, meticulously documented his journeys. He kept diaries, made audio dispatches, and took arresting photographs and videos. All of this made it possible to not only feel the nature of the continent but also how it affected Worsley.

DM: You’re used to working with all kinds of archival material and sources. Was there something different about working with Worsley’s common book? This was such an intimate story, in the end. Was the common book a big part of that?

DG: Very much so, and all of Henry Worsley’s diaries. His family is extraordinary and generously shared with me these materials. I often felt as close to Worsley as any other subject I’ve written about.

__________________________________

Read a 2017 profile of David Grann in CrimeReads.

__________________________________

DM: Stepping back to look at your works as a whole, you seem to gravitate toward two kinds of stories: crime and adventure. Obviously there are lots of subcategories within those two areas, but is there some connective tissue between them? Some similarity in the figures or the stories that draw you in?

DG: I grew up reading adventure and crimes stories, so perhaps that’s partly why I gravitate to them. Yet I never want to write the same story or revisit the same material, so each book is, in many ways, very different. It’s hard to find a clear overlap between Killers of the Flower Moon, which is about one of the worst racial injustices in American history, and The White Darkness, which chronicles a man’s perilous quest across Antarctica in the footsteps of Ernest Shackleton. What I do think connects the material—or at least what draws me to all these stories—is that they shed light on the human condition. To me, that is the greatest mystery of all.

DM: You’ve so often written about criminals, frauds, killers, and hustlers. Henry Worsley was a different kind of figure. A deeply good figure, you might say—driven (in the extreme) by characteristics we normally think of as virtuous, or noble. Was it a different kind of challenge, reckoning with a man who was on that side of the moral divide? Or is there more that binds these extreme figures than we realize?

DG: I tend to see each person I write about as so distinctive. What binds many of them, I think, is that their lives are disrupted by some force that drives them—some compulsion, some dream, some longing. What makes Worsley so fascinating is that he is a devoted family man and a person who has achieved heroic heights, and yet he feels this need to keep heading back into this brutal environment, which, at any moment, might take his life.

DM: How did you manage to preserve such suspense, such a feeling of mystery, around a story that unfolded quite recently, and in a sense quite publicly? Worsley’s tragedy is fairly well known, at least in the broad-strokes, yet reading this felt almost like reading a thriller.

DG: I always want to tell stories as the people involved experienced them. Life is always a bit of mystery, and that is especially true when you are walking across Antarctica. Henry Worsley never knew what might happen next on his journey; one misstep, and he would plunge into a crevasse. Hopefully I was able to let the reader feel that same sense of wonder and terror.

DM: With your last two books in particular, it seemed that you felt an obligation to the survivors—with Killers of the Flower Moon, to the Osage descendants; and with The White Darkness, to the family Worsley left behind. Is that something that weighs on you as you’re writing?

DG: I think it’s so important when working on a story to remember that you are not just piecing together facts. At the heart of each of these stories are real people, many of whom have suffered. While researching Killers of the Flower Moon, I collected photographs of the victims who were murdered, and kept them by my desk. They were a constant reminder of what the story was about.

DM: Speaking of Killers of the Flower Moon, the book’s massive success brought that lost history into the limelight and went a long way toward ‘solving’ a terrible crime. In the year and a half since the book was first released, have there been any new developments or revelations for the Osage people? Have you stayed in touch with the community as the story penetrated the broader culture?

DG: I couldn’t have written Killers of the Flower Moon without the help of the Osage. Over the years, many of them have become close friends and I’ve continued to keep in touch with them. In fact, I just recently returned from another visit to Osage County.

And I still occasionally receive new bits of information about the Osage Reign of Terror. Sometimes it’s a clue about an unsolved murder. Sometimes it’s an archival photograph, which I had not seen before. To me, history is a living organism, in which there is always more to add. At some point, I might try to pull some of these details together into a piece. And my hope is that others will continue to add to the story and make it part of our national consciousness.