Ever since the 1930s and the advent of the “paperback revolution” in English-language books, publishers have sought to make their creations not merely inexpensive, but distinctive. One of the notable successes in that regard was also one of the earliest. For about a decade, beginning in 1943, American publishing house Dell—which had started out in 1921 producing pulp fiction magazines, and in 1942 followed rival Pocket Books into the mass-marketing of compact, cut-rate, and sporadically abridged softcover reprints—launched a numbered line of works branded with stylistically recognizable cover paintings and backed by detailed diagrams of where events in each story took place. Those “mapback” editions were popular at the time, and over the decades have become collectible.

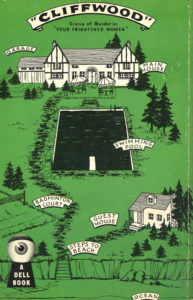

Dell debuted its cartographic gimmick with the 1943 release of its fifth paperback, Four Frightened Women, by George Harmon Coxe. (Dell Book #4, Ellery Queen’s The American Gun Mystery, was originally sold with less-interesting rear-side art, only to later be reissued as a mapback.) The company went on to turn out more than 570 additional titles in this line. Early mapbacks boasted sturdy wrappers and cleverly crafted, upfront descriptions of their dramatis personae (such as the following gem, from the 1950 edition of Coxe’s Murder with Pictures: “Sam Cusick, a notorious gangster, is scrawny, thin-faced, with a long, drooping nose. He looks harmless—except for the expression in his rat-like eyes”). Yet it was the carefully executed scene-of-the-crime layouts—touted initially by narrow front-cover banners reading “with crime map on back cover”—that set Dell’s paperbacks apart from the competition.

Mapbacks were published across a gamut of genres (each identified by a variant of the company’s keyhole colophon). At least half of them, though, were mystery, detective, or suspense novels, both of the traditional sort (by Agatha Christie, Mignon G. Eberhart, John Dickson Carr, and others) and those concocted by harder-edged scribblers (Dashiell Hammett, Erle Stanley Gardner, Margaret Millar, Brett Halliday, etc.). The focus of those books’ back-cover diagrams varied widely, but they can roughly be broken down according to three progressively widening perspectives.

FLOOR PLANS

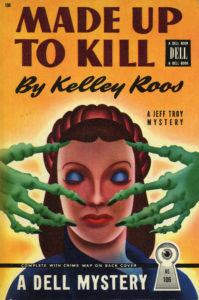

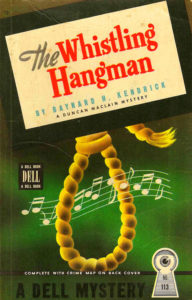

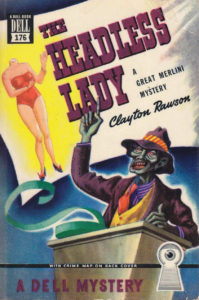

Credit for the original paintings that fronted the mapback editions is shared by such once-hard-working whizzes as George A. Frederiksen, Bob Hilbert, Victor Kalin, Willard Downes, and William George Jacobson. Dominating the field, however, were two successive Dell staff stylists: Gerald Gregg, a Colorado-born artist who—by employing an atypical airbrush technique and stark imagery—gave more than 190 of the initial installments in this series a surrealistic look; and Kansas native Robert Stanley, whose bent toward greater realism, and his taste for visual violence and sexy (sometimes semi-nude) women, can be appreciated on a reported 242 Dell covers, among them the only one the company ever altered—1951’s Fools Die on Friday, one of the Bertha Cool/Donald Lam private-eye novels Gardner penned as “A.A. Fair.”

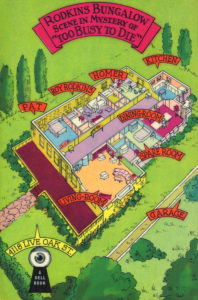

Certainly the best-remembered of Dell’s mapmakers is Ruth Belew, a rare women laboring within the male fraternity of mid-20th-century paperback designers. Biographical information about Belew is sparse, but she was evidently a Chicago illustrator, who—working from clues and descriptions in each book’s narrative—rendered her crime scenes on cardboard, at twice the finished paperback dimensions. She often added nifty identification banners and numbered “keys” to help readers locate rooms or landmarks integral to the plot. Dell editors double-checked the accuracy of her drafts, requested any necessary changes, and then sent them to lithographic colorists who’d fill her compositions with arresting hues.

Although Belew drew an estimated 150 Dell maps, earning the series invaluable attention, her name appears nowhere on those books. Her story-site depictions featured cities and castles, country estates and cross-sections of ocean liners. But some of her most memorable were floor plans of apartments, standalone homes, hotels, and business offices where fictional lives or reputations were lost. A prime example can be found on Too Busy to Die (1944), written by food-industry exec-cum-author H.W. Roden and starring his series protagonists, gumshoe Sid Ames and public relations consultant Johnny Knight. Roden’s tale is a screwy caper involving diamonds, a craps-playing butler, and a pint-size blonde bombshell, but Belew brings some order to it all with her cutaway portrayal of the Rodkins Bungalow, where part of the action takes place.

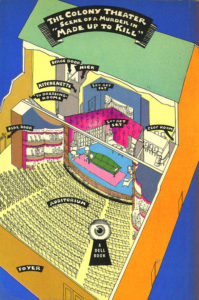

Another sort of setting is delineated on the reverse side of 1946’s Made Up to Kill, by Kelley Roos (a joint pseudonym employed by husband-and-wife authors Audrey Kelley and William Roos). In that drawing, we are offered a rather modest Broadway theater, where a soon-to-be-married pair of amateur detectives try to figure out who poisoned an ingénue and stabbed a leading lady to death.

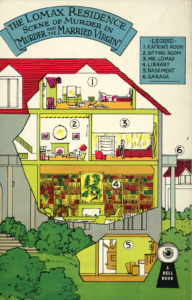

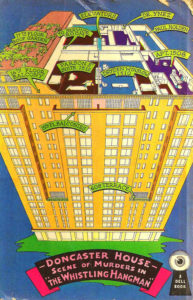

Murder and the Married Virgin (1949) is one of dozens of books Halliday wrote about carrot-topped private investigator Michael Shayne. Here, the P.I. is in New Orleans, examining the case of a soldier’s fiancée who supposedly committed suicide while doing maid duty at the home of the prosperous Lomax family—the same residence from which a priceless emerald necklace went missing not long before. Belew’s cross-section of that property helps readers to understand the relationship between rooms integral to the mystery. Her artwork for Baynard H. Kendrick’s The Whistling Hangman (1946) shows the uppermost level of a New York City hotel, the Doncaster House, where an unwell millionaire—freshly returned from Australia to America after two decades—houses himself and his covetous family. As expected, murder ensues, and blind gumshoe Duncan Maclain (who inspired James Franciscus’ 1971 TV series, Longstreet) is called in to determine not just whodunit, but howdunit.

THE BIRD’S-EYE VIEW

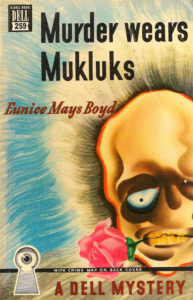

When folks write about the Dell Mapbacks these days, they tend to concentrate on the line’s most celebrated crime-fictionists. Yet for many of the authors, this chance to be published alongside Hammett, Gardner, and Dorothy B. Hughes did little to ensure their enduring renown. For every Dell release by Mary Roberts Rinehart, there was a more forgettable one by, say, Blair Traynor (She Ate Her Cake, 1947); for every Rex Stout, there was a Gerald Butler (Kiss the Blood Off My Hands, 1947); for every Helen McCloy, a Kurt Steel (Judas Incorporated, 1948); and for every Anthony Boucher or Geoffrey Homes, there was a Eunice Mays Boyd.

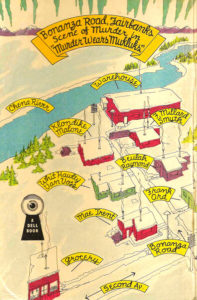

Eunice Mays Who, you ask? Boyd was an American who, long before Dana Stabenow or John Straley—and even prior to Alaska gaining U.S. statehood—formulated a trilogy of mysteries set in the Last Frontier. Murder Wears Mukluks (1948) is the final and probably best-recalled of those three, if only due to its chortle-worthy title. Published originally in 1945, the book stars F. Millard Smyth, an older, mild-mannered grocer in the interior town of Fairbanks. While fretting over his store’s debts, Smyth is visited one night by the seeming apparition of a beautiful dancing woman. The next morning, the man to whom Smyth owes money is found dead, and everyone along the grocer’s small stretch of Bonanza Road looks to have had a motive for offing him. Belew’s illustration of the snow-covered neighborhood—incorporating Smyth’s home, the adjacent warehouse where he saw the spectral maiden, and the nearby Chena River—gives readers an understanding of where the suspects in Boyd’s book live, and their access to the homicide site.

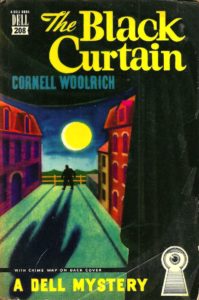

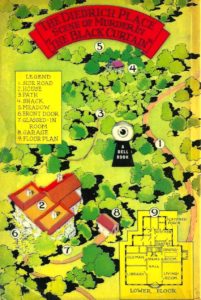

No less helpful is the layout backing Cornell Woolrich’s The Black Curtain (1948). That novel is a paranoia-packed thriller about Frank Townsend, who—after suffering from amnesia for three years—seeks to recover his memories, and also prove that he did not, during his previous life, slay the gent who employed him as a groundskeeper. Belew’s map portrays the Diedrich estate, the scene of the crime to which Townsend returns…only to find himself captured by the real murderers.

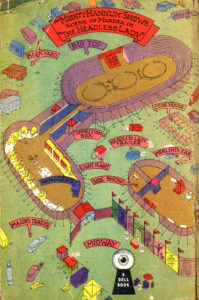

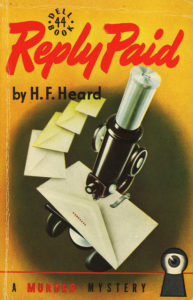

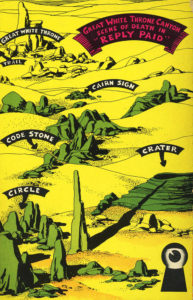

Our last two grounds-orientation maps come from The Headless Lady (1947), in which Clayton Rawson’s magician-detective, The Great Merlini, tracks a mysterious woman to a circus and winds up solving the car-crash demise of that amusement show’s owner; and H.F. Heard’s Reply Paid (1944), in which Mycroft Holmes—yes, Sherlock’s usually less-energetic sibling—chases a killer from England to the alien world of Southern California, and there gets mixed up with codebreakers and the pursuit of a highly valuable mineral.

REGIONAL REPRESENTATIONS

Early Dell maps most often concentrated on individual rooms, private dwellings, small communities, and parks or penthouses where murders, kidnappings, and other transgressions of societal order occurred. Fewer of them captured broad geographical territories and cities. However, as the series went on, the drawings became increasingly stylized and less tightly focused.

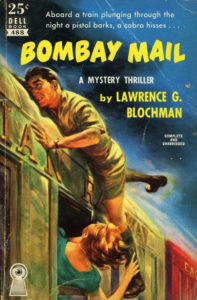

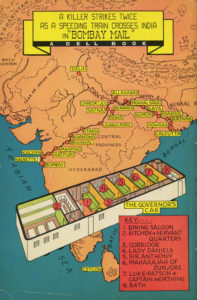

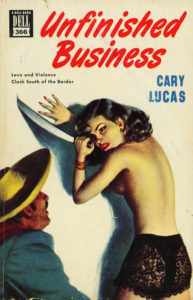

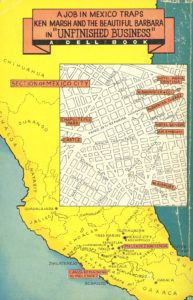

For instance, on the flipside of much-traveled journalist Lawrence G. Blochman’s debut novel, Bombay Mail (1951), we see the Indian subcontinent, through which Blochman sends his Inspector Leonidas Prike speeding aboard the historic Bombay Mail train, as he endeavors to solve the poisoning of a titled Englishman and the shooting of a maharajah. Meanwhile, a not-too-detailed representation of Mexico City backs Unfinished Business (1950), Cary Lucas’ yarn concerning efforts by the newest employee of an American pump manufacturer to locate his suddenly missing boss, while steering clear of ruthless conspirators.

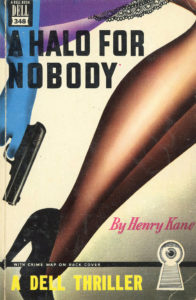

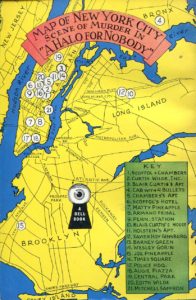

Our concluding two mapbacks return us to the States. Henry Kane’s A Halo for Nobody (1949) marked the initial outing for his fashionable, womanizing, and habitually wise-cracking New York City shamus, Peter Chambers. In these pages we find Chambers witnessing the street shooting of Rochelle Pratt Curtis, whose jeweler husband soon afterward hires the P.I. to probe both his spouse’s expiry and a recent blackmail threat against him. Chambers’ investigating sends him far and wide, and the back-cover map of the burg’s boroughs tracks many of his stops.

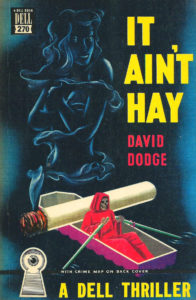

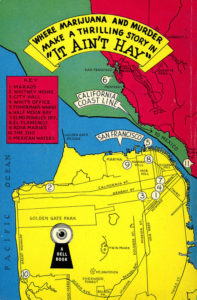

From Gotham, we head out west to San Francisco, the setting for It Ain’t Hay (1949), a dark tale that has surprisingly hard-boiled certified public accountant James “Whit” Whitney aiding police in the apprehension of a client who’s been smuggling “hay” (marijuana) from Mexico to the Bay Area. Dodge, most familiar as the author of 1952’s To Catch a Thief, doesn’t let his story’s action stray far from downtown San Francisco, so the art on the rear of It Ain’t Hay is nowhere near as intriguing as Gerald Gregg’s cover painting, which shows Death rowing a coffin-shaped boat overloaded with a giant smoking joint.

By 1952, rear-side maps started to appear less regularly on new Dell paperback releases. It did not take long for them to vanish entirely, replaced by conventional story descriptions and critics’ hyperbole. Not until decades later was there a significant revival of interest in this series, thanks in part to the publication in 1983 of William H. Lyles’ scholarly study, Putting Dell on the Map: A History of the Dell Paperbacks.

Since then, there have been a few tributes to the Dell mapbacks, in the form of publishers adopting that classic format for their own—as Uglytown Productions did with its 1998 “bowling alley murder mystery,” By the Balls, by Tom Fassbender and Jim Pascoe. But really, the best way to honor that vintage line is to track down the books for yourself. Despite more than half a century having passed since their printing, mapbacks are still widely available from used bookstores and online sources—distinctive as ever, if no longer quite so inexpensive.