When I came to Hollywood in my mid-twenties, having published two novels and determined to crack into the screenwriting business, I had a long-term dream. One day, I wanted to write a good thriller novel and turn it into a hit movie myself. I was convinced that if I ever achieved the power to control my own adaptation, I could move from the written word to the silver screen judiciously and preserve the story and character elements that worked, while giving myself the freedom to change what needed to be changed. Who better than the author to adapt his own book?

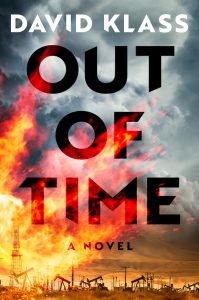

Now, after a thirty-year career in Hollywood, having written more than forty action screenplays for the studios and twenty novels, I am finally getting my wish. My new novel, Out of Time, an eco-thriller in which a ‘green’ terrorist and a brilliant young FBI agent face off, is being published by Dutton on July 7th. It has been optioned for a movie by Netflix and I am busy doing the adaptation myself. But after three decades of working in Hollywood, I am proceeding very cautiously. I now know that my youthful dream comes with significant dangers.

Novelists are always bemoaning the damage that Hollywood adaptations do to their precious books. In mysteries and thrillers, where the trail of clues and suspense elements must be carefully calibrated, altering the structure and logic of the novel would seem to be especially dangerous. But is it actually a good thing for movies to hew too faithfully to the successful novels they’re based on? And is it a wise thing for the original creative voice—the novelist—to try to dramatize his own book?

The history of adaptations in Hollywood shows that it can be dangerous for the author of a book—no matter how versed in screenwriting—to try to control the adaptation. One voice—even if it is the voice that spun the original story and gave birth to the characters—may not be the right one to tell the screen version. By being over-protective of their prose material or alternately too willing to show their malleability and give up what was working, novelists often turn their own beloved books into movies that clank and clunk. Strangely, a second or a third creative voice often leads to wiser choices and a stronger movie. And there is an argument to be made for near complete chaos.

Strangely, a second or a third creative voice often leads to wiser choices and a stronger movie. And there is an argument to be made for near complete chaosPerhaps the best adaptation of a book to a movie is The Wizard of Oz. L. Frank Baum’s magical novel of Dorothy’s journey from Kansas to the Emerald City became a classic 1939 movie that seems to work on every level of story and character. Surely, in the creation of such a seamless and glistening jewel of a movie, there must have been one wise and controlling voice making the decisions?

Actually, at least eleven different writers worked on the adaptation and the lyricist, Yip Harburg, who is not credited as a screenwriter, also made key contributions. The development process was random and frenetic. At one point, three different screenwriters were working on different versions simultaneously. There were attempts to remove all magical elements from the story, create a romance between Dorothy and the Hunk/ Scarecrow character, and hold a swing-style singing contest between Dorothy and a princess of Oz. Yet somehow all these different creative voices and developmental chaos came together to create a near-perfect movie.

When I studied movie structure at USC Film School, I was taught that the perfectly structured Hollywood thriller was The African Queen, adapted from C.S. Forester’s novel. The adaptation is credited to James Agee and the director John Huston, but actually contains the uncredited contributions of a number of screenwriters including John Collier and Peter Viertel. The screenwriting process was chaotic and continued into production in Africa, where John Huston hunted elephants, drank prodigiously, and tinkered with the script to suit his superstar cast and his dear friend Humphrey Bogart. In the novel the Charlie Allnut character was from England but when Bogart couldn’t render an acceptable Cockney accent the character’s background was changed to Canadian. Despite the hodgepodge of different screenwriters and a chaotic development process—with significant story and character changes from Forester’s novel right through to the ending—it is now held up in film schools as the thriller that all screenwriters should study.

My favorite thriller novel growing up was Marathon Man by William Goldman, which I must have read a dozen times. I loved the fun and pace of the novel and the vivid characterizations and outrageous moments like Babe, a history graduate student at Columbia, being ripped out of the bathroom of his apartment to be tortured by a dentist who keeps asking him: ‘Is it safe?’ If any thriller seemed primed for an easy transformation to a great movie it was this one—especially with Laurence Olivier playing the World War II war criminal dentist and Dustin Hoffman as the nerdy history student who must fight for his life.

William Goldman—perhaps the premiere screenwriter of his generation—adapted his own novel, and had great control. Robert Evans, the producer, correctly said that ‘This book reads like the movie-movie of all time.’ Given Goldman’s mastery of screenwriting, he felt compelled to change and improve numerous elements of his own novel, and he sliced character backstories, removed what he felt were extraneous storylines and opted for extensive crosscutting. Somehow this great screenwriter, given the power to adapt, changed too much and wrote a flawed movie that loses much of the coherence and deep characterizations of his novel. Robert Towne—the Academy Award winning screenwriter of Chinatown—was brought on at the end for a touch-up, but Goldman wrote the great majority of the script and received the full screen credit, so he had no one to blame but himself for a less than stellar adaptation.

In contrast, the 1991 thriller The Silence of the Lambs is based on a terrific novel by Thomas Harris. Harris is a novelist who craves privacy and is not a screenwriter. Ted Tally did the adaptation, and had the wisdom to pretty much leave Harris’s vision untouched. For this hands-off approach, Tally was deservedly given the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay and Harris emerged as the novelist who wrote a bestselling thriller that also won an Oscar for Best Picture.

In my own career, I adapted James Patterson’s novel Kiss the Girls and was amazed by how supportive Patterson was to a relatively young and untested screenwriter. Perhaps it was his background in advertising, but Patterson was open to hearing my ideas on changing character and story beats and he read drafts of key scenes that had been changed and called me with suggestions. Adapting his novel with his own enthusiastic help, and with the advice of legendary producers David Brown and Joe Wizan, could not have been more collegial.

In contrast, I helped adapt Julia Alavarez’ fine novel In the Time of the Butterflies into the movie starring Salma Hayak and Edward James Olmos. Because the novel was so vitally important from both a feminist and historical standpoint, Alvarez understandably felt protective of her story and characters and questioned many of our proposed changes. While this ultimately made the movie stronger and more accurate, the adaptation process was challenging.

And when I was hired by MGM to update the iconic Seventies action movie ‘Walking Tall’ starring Joe Don Baker as the legendary southern sheriff Buford Pusser, I became my own worst enemy. I had seen the original movie several times when it came out, and I was so enamored of it that for months I couldn’t bring myself to make any significant changes. MGM grew frustrated, and then I got a dozen excited calls from the producers and studio executives telling me that The Rock had a hole in his schedule. A project had fallen through and his team was going to take a bunch of action scripts home over the weekend and pick one for him to do next. Somehow envisioning The Rock in the starring role freed me up to quickly make major changes. I moved the action from the south to the Pacific Northwest and gave the main character a military background. The Rock took the part.

With these cautionary stories in mind, I am now making the decisions on what to keep and what to change in turning my own novel Out of Time into a movie. Luckily I am being guided by several highly experienced and wise producers and studio executives. Every time they make a suggestion that I find myself dismissing out of hand, I catch myself and say: ‘Dummy, the fact that it works in the novel doesn’t mean that it belongs in the movie. But it also doesn’t mean that you need to change too much. Don’t be protective. And don’t give up too much of what’s working. Be humble. Listen to other voices. And allow an element of chaos.’

***