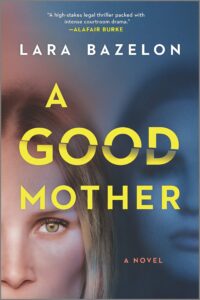

Featured image: Clara Shortridge Folz, public defender pioneer

Public defenders are finally having a moment.

For decades, these lawyers and other court-appointed attorneys for the indigent were derided as the red-headed stepchildren of the criminal justice system. Often portrayed in literature and movies as bumbling, overwhelmed, and on the wrong side of justice, the real-life men and women who chose this line of work inevitably faced the question: How can you sit next to that scumbag?

But in recent years, as the nation has begun to reckon with a criminal justice system that is error-prone and rife with racial bias, this same group of lawyers is gaining recognition as leaders in the battle to dismantle it. The best known is Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Mobile, Alabama, and bestselling author of Just Mercy, a story of his fierce advocacy on behalf of clients, innocent and guilty, which was made into a major studio film in 2019.

Once considered a road to nowhere, the job is now being championed by progressives as a vital credential for appointment to the state and federal bench to balance out a judiciary long dominated by prosecutors. President Biden proudly declared his membership in this group during a 2019 debate telling the audience, “I was a public defender. I didn’t become a prosecutor.”

The recent celebration of public defenders is welcome and long overdue. But the picture is missing a crucial piece. We rightly recognize brilliant, diverse, and charismatic advocates like Stevenson, Derwyn Bunton in Orleans Parish, Brendon Woods in Alameda County, and the late Jeff Adachi across the Bay in San Francisco.

But all too often, fierce female advocates are left out of the story.

Literature and media reflect a similar gender bias. The few times that court-appointed advocates for the indigent and despised are portrayed as heroes, they are almost always men.

The central character in the short-lived TNT series Raising the Bar, which ran from 2008-09, was a self-righteous protagonist named Jerry Kellerman. His boss, played by Gloria Reuben, spent most of her time behind a desk. More recently, there was the even shorter-lived All Rise, a CBS production that mainly revolved around a prosecutor-turned-judge. While one of the supporting characters was a public defender named Emily Lopez, she was just that—supporting—with a “wears-her-heart-on-her-sleeve” personality that left little room for the complexity and nuance that make for a memorable protagonist. For the People, a Shondaland drama featuring prosecutors and defenders facing off in federal court was cancelled so quickly that no character arcs had time to develop, as was true for In Contempt, a BET show that ended after one season.

It isn’t easy to find a gutsy, no-holds-barred female public defender protagonist in crime novels, either. Consider Kennedy McQuarrie in Jodi Picoult’s 2016 bestseller Small Great Things. Tasked with defending a Black nurse, Ruth Jefferson, accused of killing the baby of a white supremacist couple, Kennedy’s courtroom advocacy is cringeworthy. Here I defer to Roxane Gay’s on-the-nose takedown in her New York Times book review, “There is even a moment in her closing argument when Kennedy says: ‘When I started working on this case, ladies and gentleman, I didn’t see myself as a racist. Now I realize I am.’ Girl, I guess.”

Why are women public defenders rendered flat, sappy, or just plain invisible? The answer is two part. In real life, the legal profession is historically chauvinistic, explicitly blunting women’s advancement for more than a century before turning to more subtle maneuvers. There are fewer of them—the pressures of work and family, the unforgiving climate, thin their ranks.

But there is a more specific problem when it comes to shining a spotlight on the fictional Davids who go up against Goliaths. The alchemy of qualities that make a great public defender: righteous indignation, contrarian outspokenness, and shoot-for-the-moon boldness are acclaimed in men. The same qualities, embodied by women, land differently. An angry male advocate in pursuit of elusive seeming justice is given the benefit of the doubt. Not so his female counterpart.

Cool-as-a-cucumber corn-husk-haired prosecutors and their jaded brunette older sisters are familiar figures, to be sure. Whether it is real life’s Nancy Grace, Law and Order SVU’s interchangeable icy-blonde, or Alex Cooper, the “tough, brassy” assistant district attorney in Linda Fairstein’s bestselling series, we know the prototype. They exist to perpetuate a previously acceptable narrative: defendants are scum, victims must be avenged. Rarely, if ever, do female prosecutors occupy the heart of the narrative. Usually they are cardboard cutouts, all business, devoid of an inner life. And if the plot calls for their pat case narrative to be exposed and skewered, it is usually by a male opponent.

Public defenders are a different species. They speak for the accused, the despised, the Other. To do so in a way that brings credit not only to the case but to the client requires a baseline presumption of competence and ferocity to which female trial lawyers generally are not entitled. Too often, the need for them to be likeable, self-abasing Kennedy McQuarrie types turns them into caricatures. And that is when they are permitted to exist at all.

As complicated female protagonists take center stage in other genres—action films, bio pics, and detective novels—it is time to rethink defaulting to these reductive stereotypes when it comes to courtroom dramas. It is time to say good-bye to the lawyerly version of the girl next door.

Let’s step forward and embrace history at the same time. The very first public defender’s office in the United States was founded by Clara Shortridge Foltz. Foltz, a single mother of five, went to law school in the 1870s, after her husband left for another woman. She had to sue the state of California for the right to practice, emerging victorious after the state’s Supreme Court ruled in her favor. For years, she labored in the trenches for clients without the means to defend themselves, having to put up with arguments such as this one: “she is a woman, she cannot be expected to reason, God Almighty declared her limitation . . . this young woman will lead you by her sympathetic presentation to violate your oaths and let a guilty man go free.” (Reader: she won).

Clara’s name is on the downtown criminal court building in Los Angeles, but other than this recognition and Barbara Babcock’s excellent 2011 biography, Woman Lawyer, she is largely consigned to the margins of history. Where is the line to scoop up the film rights to the life and times of this amazing female trial lawyer? Who are her descendants, in real life and in literature?

The truth is that there are thousands of women like Clara in the real world, their courtroom dynamism, theatrics, audacity, and success largely obscured. Included on that list is the late Babcock herself, the former head of the esteemed Public Defender Service in Washington, D.C., and a renowned Stanford Law professor.

We do women trial lawyers a disservice, in real life, in books, and on screen, ignoring both their past and present contributions to the profession and the rich raw material they provide as a foundation for fictional characters.

“Unlikeable, but never boring.” That is what Publisher’s Weekly called my fierce, flawed, public defender protagonist, Abby Rosenberg. I take it as a compliment.

It is time for these women to take center stage. Long past time.

***