When you talk about barriers to entry, Gayle Lynds could write a book.

Well, she did. Several in fact.

The New York Times bestselling author remembers her struggles to get her first thriller manuscript published under her own name, even if she had the advantage of already having ghost written several novels under contract. But when she set out to write her own, she crashed into a bulwark of sex discrimination in the exclusive male spy genre—and it wasn’t just men blocking her path.

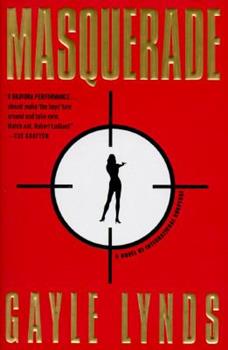

Yet there isn’t a hint of cynicism or anger in her voice when she talks about her history leading up to becoming one of the most popular spy novelists in the world. It started with, Masquerade, proclaimed not only a thriller classic, but Publisher’s Weekly ranked it the eighth best spy novel ever written.

In the process she persevered and overcame her own insecurities. She had wanted to write since she was a teenager but believed authorship was for other people, not her. “I didn’t think I could write novels,” she says. “That was the purview of gods and goddesses.”

She learned writing by reading obsessively and listening to adults’ stories. “In Iowa, I called it the kitchen table culture,” she says. Her mother’s friends in the neighborhood would drop by the house around ten each morning for coffee and would tell stories—just every day stories. She listened and it was the beginning of her education in the art of storytelling.

It was a lonely upbringing in a small Iowa town. So she buried her head in books. She read so much to fill her time that by age ten her mother had no choice but to give the local librarian permission to allow Gayle to read adult books.

After high school she left for the University of Iowa, home of the famed Iowa Writers Workshop. Her intention was to obtain a degree in journalism, not creative writing. She did not consider herself a goddess, but still as an undergraduate she would sneak into some of the creative writing sessions at the Writers Workshop and hang out with the graduate students.

“I drank at ‘Docs’ (a local watering hole) with those students. The amount of alcohol consumed was just stunning and the amount of sex under the table was eye opening for someone from Council Bluffs Iowa,” she says.

She married Tom Stone while still an undergrad. After graduation, she landed a job at the Arizona Republic newspaper in Phoenix, and quickly ran into her first on-the-job case of sexual harassment.

“I opened my desk drawer one day and there was a ripe banana. I complained and they put me at the obit desk for two weeks as punishment.” But Gayle couldn’t help herself. She was, after all, a creative person. So she convinced a newsroom rookie that writing obits was a great way to start a career and she was off the desk in a week.

She was not only creative, but serious. While at the newspaper, she wrote a three-part series on how Arizona was literally shortchanging mentally disabled children and adults. While researching her story, she says, “Everyone I met had an attorney with them. It made my antenna wiggle. They gave me nothing so I asked to read the financial records. I started running the numbers and could see the money they claimed they were spending on those handicapped children and adults wasn’t accurate. They were spending much less.”

Her stories led to reforms and more funding from the state.

THE IDEA FACTORY

Gayle and Tom returned to Iowa for a year so he could finish law school. He then landed a job at a firm in Santa Barbara, California, so they moved to the West Coast. What was she to do? She recalled a conversation with famed author Kurt Vonnegut—a lecturer at Iowa—who told her he worked one summer at a think tank. He found it an amazing experience because, “They were bouncing ideas off the walls,” she says. “That’s where he got the idea to write his bestseller Cat’s Cradle.”

Inspired, Gayle landed an editing job at GE-TEMPO, the Technical Military Planning Operation, a Santa Barbara think tank owned by General Electric that had several secret government and military contracts. And several floors above her basement office was DARPA, the Department of Advanced Research Projects Agency. The building was a gold mine of ideas for a writer.

“I received a Top Secret clearance, and a wealth of fascinating experiences in secrets and their power,” she says. She edited scientific manuscripts and wrote abstracts for the firm. Security was so tight, if she went to the bathroom, she would first have to lock her writing and paperwork in her office safe. To enter another department she had to key in a code. People often arrived using no names or used only first names in meetings.

“Half the time I’d forget my badge to get in the building,” Gayle says. “I was hopeless.” But she never forgot the rumors around the water cooler. “It awakened in me the sense of the possible, of the unknown that I wanted to know about. And of the power of secrets because I dealt with secrets all the time… It really taught me about a complexity of life that I had not grown up with. It was sophisticated, worldly.”

She left after three years when her first child, Paul, was born. “I was a busy housewife, and our second child, Julia, soon joined us. I baked brownies, sat on the boards of PTAs, chaperoned school trips—everything and anything. It was a sweet period in my life, but at the same time I hungered to write.”

TIME TO DREAM

So Gayle took writing classes through the local adult education program and studied at the annual Santa Barbara Writers’ Conference. There, she says, “I met people like me. It was such an eye opener to think my dreams were possible to achieve.”

“Through adult ed I was fortunate to attend a weekend workshop with Robert Kirsch, the storied literary critic of the Los Angeles Times.” By then she’d written two unpublished novels and several short stories. “He believed in me. He told me one time, ‘Gayle, you’re an artist.’ And I broke into tears. I’d had so little support until then. And he didn’t hand out compliments.”

He told me one time, ‘Gayle, you’re an artist.’ And I broke into tears. I’d had so little support until then.

“Bob liked my work and started mentoring me, and paved the way for me to study at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference in 1980.” But while she was there, Kirsch died of cancer. “He had a profound impact not just on my writing but also on my life. I still miss him.”

Later that year Gayle and Tom divorced and shared custody of their children. She was publishing short stories that fed her emotional sustenance, but didn’t pay the bills. “I was being paid in copies of literary journals, but paper is not a food group for kids.”

So she polished off her journalism credentials and took an assistant editor’s post at Santa Barbara Magazine, where she eventually became editor.

Then she met novelist Dennis Lynds speaking at a writers workshop. “Den was eye-opening for me. I’d listened for years with growing consternation to the ongoing arguments about which was better—literary or genre writing. I didn’t understand why one couldn’t write in the genres at the high quality level of so-called literary writing. Seldom did I find anyone who agreed with me.

“As I listened to him that night, I was stoked to finally find not just anyone—but an exceptionally well published, award-winning author in both detective novels and literary fiction—who was saying what I’d been thinking.”

Dennis followed her out of the room, and thus began their writerly romance. They married in 1986.

“One day he asked whether I could write male pulp fiction,” she says. “It was quite a change from literary fiction, but I lied and said ‘yes.’” So Dennis got a contract to write three Nick Carter novels, a popular pulp fiction series at the time, and Gayle and Dennis began talking through plot ideas. “By seeing the structure, I was eager to write, and writing gave me the chance to experiment with voice, story, suspense and strong female characters.”

The contract remained in Dennis’ name even when she wrote the books. “I couldn’t get the contract as a woman, and even if I had, they would have paid me less.” She and Dennis split $2,500 a book, and there were no royalties or author credit.

She used that experience to pen two Mack Bolan novels, a character some referred to as an American James Bond. And the contract this time was in both her and Dennis’ names. So when it came time to close an issue of Santa Barbara Magazine where she was still working, she turned the Bolan reins over to Dennis to complete.

“I didn’t have time to write the whole thing and put out the magazine. It was income. We lived on a banana peel because both of us were writers.”

OTHER PEOPLE’S RULES

She also wrote three novels in the “Three Investigators” YA mystery series published by Knopf, but her editor told her, “Boys won’t buy books written by girls.”

So she used her initials instead of a first name—one more step on her journey to be recognized for her work.

“Writing different kinds of books with different limitations was a training ground I’ve always been grateful for.”

Then the bottom fell out of the work-for-hire market.

“At the same time I got a job as the executive assistant to a millionairess, so I had some income coming in. It was apparent to me the best way to regain my sanity and be me, was to write a book that was really me and not based on other people’s characters and rules.”

How did she come up with the premise for the first novel that would eventually carry her name on the cover? “One day I looked in the mirror and for just a moment I wondered what it would be like to not recognize myself. Who is that woman? That’s when I wondered, how do any of us know who we are?”

She recalled a story she’d overheard at the water cooler at GE-TEMPO years earlier about the famed super secret MK-ULTRA mind control program created by the CIA. It had later been exposed in 1977 by the Church Senate Select Committee, led by Sen. Frank Church, D-Idaho, who was looking into abuses in the intelligence community.

Gayle decided using mind control would be a good start.

DUMPSTER DIVING

In the late 1980s Gayle was reading the newspaper when she came across a story about the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, the largest private bank in the world. It was caught in a scandal of international money laundering and self-dealing. Days later it occurred to her that might be exactly what she needed for her new manuscript. “I was fascinated, especially with all the links to espionage,” to say nothing of all of the rich and powerful people and international locales—perfect tools for her manuscript.

She looked around the house and found she’d already thrown out all of her newspapers. “I realized the newspaper stories would be perfect for Masquerade. I never had a lot of shame when it came to good research.” So she did what every enterprising writer does. She went dumpster diving in the Mesa neighborhood of Santa Barbara.

“I got a ladder. I jumped in. It was behind a strip mall and I began digging for newspapers.”

“I got a ladder. I jumped in. It was behind a strip mall and I began digging for newspapers.”

Her fascination with financial crimes didn’t stop there. A little over a year later she and Dennis were in Las Vegas at the poker table when an electronic ticker tape in the casino announced American investor George Soros had broken the Bank of England, earning himself a billion dollars in a single day.

“I was winning at seven card stud. It’s bad form to leave a poker table when one is up a lot, but I grabbed my chips and excused myself. Ribbing and boos followed as I hurried off. My brain was afire. I knew I could use the bones of the story somehow in Masquerade, and now I had to figure out how.” She immediately purchased several newspapers and went up to her room to start reading. “I knew from the get-go that it’d give me what I was looking for.”

Finally, she felt she had all the kindling she needed to write her story. She dove in. But a year later, she still wasn’t satisfied. “It wasn’t good enough. I knew it wasn’t good enough.”

Dennis’s agent sent out the manuscript to test the waters and she received 30 rejections. An editor told her, “You need a story that will carry it from beginning to end.”

At that point Henry Morrison, who was also the agent for Robert Ludlum and her friend David Morrell, took it on. “I can help you get this to midlist,” Morrison told her, “but if you rework it, I think we can sell it at a higher level where it will get the support it deserves.”

“I couldn’t find any classes on how to write a thriller. There was nothing for thriller writers… To hold the thing together, I needed one over-arching plot,” she says, “plus the unveiling of an assassin.”

Gayle went through the entire manuscript. “I call it chaptering,” she says. “I made a list of the chapters, two or three descriptive sentences per chapter. By doing so, I could see repetition of scenes and characterization. I took out an entire day in the plot. I condensed the first 150 pages to just two chapters. Then I tightened the last 150 pages. The point was to make the book not just a so-called fast read, but one that was highly suspenseful without sacrificing character or story.”

“I was writing part-time, but I knew I had something. I could tell. I just hadn’t known how to pull it off.”

“Henry sent the book to Elaine Koster, publisher at Dutton, who told him she loved it, but “no woman could have written it.”

“Gayle knew her way around the spy world, but in the 1990s, editors, obviously mostly male, didn’t believe a woman could know anything about spies or be accepted as an author of books about them,” says David Morrell, author of First Blood, the novel that introduced the world to Rambo. “Gayle has a major place in the history of thrillers because she changed that perception.”

A woman who feared Gayle’s book wouldn’t be taken seriously in her chosen genre had turned her down, but Gayle wouldn’t give up. “You’d think by then I’d have been used to it. I was even more determined to prove that women could write successfully and very well in the field.”

Morrison then sent the manuscript to Steve Rubin at Doubleday (who had edited John Grisham and later Dan Brown). “He loved it.”

She thought she’d made it. Bertelsmann, her publisher’s parent company, moved Rubin to London. Management brought in a woman to replace him. She was not as enthusiastic about Gayle’s book. Originally, Steve planned an auction for the manuscript, saying he would do for her book what he did for Grisham’s The Firm. It didn’t happen.

And to make matters worse, her publicist, also a female, left Doubleday.

“My career has been one disaster followed by a victory, followed by a disaster,” Gayle says. “I think that’s true of most writers.”

“My career has been one disaster followed by a victory, followed by a disaster,” Gayle says. “I think that’s true of most writers.”

Finally, Doubleday published Masquerade in hardcover. Gayle went on tour and visited a hundred bookstores, signed hundreds of copies, talked to bookstore employees and endured untold number of interviews to promote her novel. The book sold well, but nothing spectacular.

Then fate stepped in. This time a woman got behind her. Doubleday shipped Masquerade with other books to Phyllis Grann at Berkley Paperbacks. She loved it. At a marketing meeting she held Masquerade up and waved it before the assemblage proclaiming, “See this book? It’s a great book. We’re going to make it a bestseller.”

Grann kept her word and Gayle Lynds made history.

Masquerade rose to Number 17 on the New York Times Bestseller List. It came out of nowhere. Hundreds of thousands of copies were sold. She was finally a bestselling spy novelist. She was only the second woman to ever break that glass ceiling.

The novel was so popular that several years later St. Martin’s Press bought the rights and reissued it and Publishers Weekly proclaimed it one of the ten best spy novels ever written. Gayle went on to write numerous best selling spy novels and continues to be one of the most popular thriller authors in the world.

She has never forgotten her past struggles and decided to turn them into something positive. Early this century, she joined fellow thriller novelist Morrell to create the International Thriller Writers, a writers association that has grown larger than Mystery Writers of America and even larger than Romance Writers of America. There would be no more lack of classes for those seeking to write a thriller instead of a mystery.

And she didn’t stop there. Along with thriller and mystery writer Chris Goff, she started “Rogue Women Writers: Kick-ass Thriller Writers. With Lives” to give women who wrote international intrigue and spy novels a voice. Even in 2016 when they started, there were still reviewers who refused to read them and editors who thought they wouldn’t sell. “The welcome mat was hardly out. So it seemed a good time to let the world know we existed.” Today, the group includes nine female authors who promote and provide support for other writers.

During her career, she quickly became know as the female Robert Ludlum and was asked to work with him on his books, as he grew older. But he died before they ever met in person. After his death she wrote three Ludlum novels. Her name, this time, appeared on the cover.

“It was a chance for me to show as a woman I could write in the field. I give Ludlum credit. Nobody else would’ve chosen a woman in those years, but Ludlum did.”

Today she puts out a book about every four years. Her next is about a dissident in Moscow who hooks up with an American undercover agent. To say the least, they have trust issues. She plans to finish it in 2021.

Despite all of her success, Gayle laments that women writers still have a ways to go. Sadly, she says, “I still have readers today tell me I’m the only woman on their bookshelf.”

___________________________________

Masquerade

___________________________________

Start to Finish: 4 years

I want to be a writer: As a teenager

Decided to write her novel: 1991

Experience: Reporter, Nick Carter, Mack Bolan, YA novels under contract, literary short stories.

Agents Contacted: 2

Agent Submission: Agent received manuscript in 1993, rewrote, went to publisher early 1995.

First Published: Doubleday published 1996 Berkley Paperback published 1997

Time to Sell Novel: Weeks. “It went fast.”

Agent: Henry Morrison

Editor: Judy Kern

Publisher: Doubleday

Age when published: Over 21

Inspiration: My career has been strange. All the wonderful authors out there who every day sit down and write the best story they possibly can against great odds. We are all in this together. And that’s one reason David Morrell and I started ITW.

Website: gaylelynds.com, roguewomenwriters.com

Advice to Writers: Never give up.

Like this? Read the chapters on Lee Child, Michael Connelly, Tess Gerritsen, Steve Berry, and David Morrell.

—From “My First Time,” an anthology in progress by Rick Pullen. rickpullen.com