I never thought I’d watch a show like Evil, by which I mean I never thought I’d watch a show in which evilness was the central theme, especially in a Biblical sense. In Evil, a Catholic seminarian, a psychologist, and an environmental researcher investigate numerous mysterious events, attempting to conclude on behalf of the Roman Catholic Church if such incidents have been caused by true supernatural (often demonic) forces or have scientific explanations.

Possessions and exorcisms terrify me. I am not a super religious person, or an overly superstitious one, but I still don’t mess with content that includes those things. No, thank you. I keep my head down. I avert my eyes. And yet, I found myself drawn to Evil—and more astonishingly, I found myself drawn to it for the manner in which it relies on these unpleasant horror hallmarks, which is with the goal of exploring both goodness and evilness as concepts. Evil‘s primary investment is in redefining what evilness means to modern society, and it uses its Biblical framework as a lens to do so.

The series premiered on CBS in 2019, and was then relocated to the Paramount+ streaming service for its second and third seasons, which aired last and this year. (A fourth season is in the works, thank God.) It is a straight-up procedural (an hour long including commercials), with a mystery at the center of every episode.

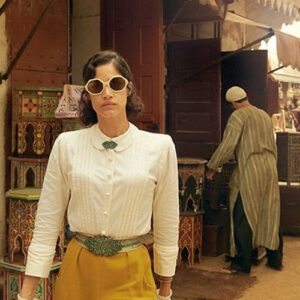

In its pilot, we are introduced to Dr. Kristen Bouchard (Katja Herbers), an agnostic psychiatrist and mother of four from Astoria who works as an expert witness in court cases prosecuted by the New York City District Attorney’s office. Her examination of a serial killer who claims to have committed his crimes under the influence of a demonic power leads her to David Acosta (Mike Colter aka Marvel’s Luke Cage), a former journalist and a priest-in-training who works as an assessor for the church, and Ben Shakir (Aasif Mandvi), an ex-scientist turned jack-of-all-trades researcher who specializes in analyzing material and technological explanations for seemingly inexplicable phenomena.

Evil‘s primary investment is in redefining what evilness means to modern society, and it uses its Biblical framework as a lens to do so.David and Ben recruit Kristen to their team, which fulfills her professionally but complicates her personal life—not only because she and David find themselves attracted to one another despite Kristen’s marriage and David’s intention to take up the cloth, but also because she quickly realizes that her own home has become a hotbed for creepy, nightmarish sights. Even her own tough-as-nails mother Cheryl (Academy Award nominee Christine Lahti), who often babysits Kristen’s four girls, suddenly seems to be a bit off, a bit wicked, at times. It becomes hard for Kristen to know who to trust, although her team does find two new allies: Kristen’s own psychiatrist, Dr. Kurt Boggs (the great Kurt Fuller), and a shrewd and kindhearted nun, Sister Andrea (the great Andrea Martin).

Kristen is barely just hired, though, when she captures the attention of Dr. Leland Townsend (Michael Emerson, oozing weirdness), a sinister psychologist and occultist who gets off on goading people to do very bad things. Kristen thinks he is a psychopath, while David wonders if there is something demonic about his whole existence (that he is a literal devil’s advocate). Either way, he becomes obsessed with Kristen, and grows dead-set on sabotaging her, David, and Ben’s positive impacts—on the people they are investigating as well as on the community at large. He is the series’s tangible villain—the series’s intangible one is, of course, the Devil, who lurks in the details of the cases brought to their attention.

Not all the cases are religious in nature, and that’s where Evil takes itself in a fascinating, new direction. The team winds up investigating or encountering many instances of systemic racism (from medical/hospital abuse to police violence), capitalistic exploitation, and ICE/deportation. The show was created by Michelle and Robert King, the showrunner couple responsible for The Good Wife and The Good Fight, and as the arc from that first show to the second made evident, they are particularly interested in using the form of the procedural (legal or detective) to highlight real problems, of systemic inequality, racism, and bigotedness (to name a few) and frame them as the true enemies of the American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Similarly, in Evil, there is an episode about the workplace oppression of Amazon-style warehouse workers, and another episode about the trauma of the Rwandan genocide, and another episode in which a child seeing horrifying visions has her Muslim mother’s wishes about how to proceed with an Islamic exorcism harshly sidelined by her Catholic father and dismissed by priests. Evil is interested in exploring human nature, first and foremost, as it has long been given an arena by the spiritual.

Notably, all the evil forces in Evil act through people, and the investigators have to determine if people’s cruelty, selfishness, prejudice, hatred, and violence result from their own minds and agencies, or if those things are the work of evil powers. Or, if they are one and the same, and the personification of evilness into “the Devil” or other figures is metaphorical, symbolizing what becomes of people when they promote those qualities. The show wonders, is true evil born in the hearts and wills of humankind, or is it put there?

Like The X-Files, most of Evil’s episodes end a bit open-endedly; there are often discernable explanations for many of the strange phenomena the team encounters, though there are usually a few lingering questions that don’t seem to have answers at all. It seems that there is something menacing afoot in Queens but it’s often hard to say; sometimes people just do bad things on their own, and there is a human urge to find a motivation (psychological, supernatural, environmental) for whatever the hell is going on.

When I watch Evil, I’m not (as I used to expect) scared out of my wits, so much as outwitted from being scared. The series is too invested in analyzing the evils of our modern moment (Trumpism, gun violence, incel culture, Anti-Black racism, and many more things, including the evils perpetrated by the Church itself) for it to seem scary on a visceral level. It takes on themes that are scary on political, economic, and societal levels, looking them in the eye and calling them out for what they are. My jaw dropped when, in an episode from the first season, a credible prophet of God (Li Jun Li) whom the team is investigating informs them that Jeffrey Epstein was murdered in a cover-up to protect more abusers. And Evil has only gotten more gutsy and progressive with its episode plots after making the pivot away from primetime and finding a home on a streaming service.

Despite the fact that it contains such nuanced readings of the Bible as to rival the masterful ones in Mike Flanagan’s Midnight Mass (and I do NOT say that lightly), Evil isn’t about Catholicism all the way—it clearly acknowledges that the Christian conceptions of evil and its personification of those forces as Satan, Lucifer, “the Devil” are just that: conceptions. They are characterizations of a force whose intrinsic makeup defies religious categorizations; most religions include room for elaborations on and figures of evilness, and Evil is aware and inclusive of those themes. In addition to Catholicism, the series is also invested in Islam, and its meditations on and figures of evil are often enmeshed in Ben’s storylines. Ben is a lapsed Muslim and an avowed realist; he eschews all supernatural and faith-based abstractions, determined that the material, physical world is the source for all possible knowledge.

Evil is very clear that humans (under the thumb of something evil or acting of their own evil accord) will always find ways to reach one another to sow discord, promote hate, and recruit others to their cause if they are so inclined. In this way, the show is also curious about our relationship to technology. So much of the story’s alleged demonic activity (and the spooky stuff going on in Kristen’s own house and to her four children) is tech-based. VR goggles allow the kids to play a game which a stranger joins and tries to get them to do certain unnerving things. 4chan is a recruiting ground for militia-style gangs within the NYPD. An earwormy song promoted by a viral video from an influencer contains coded messages urging kids to hurt themselves.

The show acknowledges that today’s online culture is an unregulated Wild West for many kinds of nefarious work. Evil doesn’t condemn technology on its own, but represents it, like most things, as cloven. And the series is interested in tracing how, in addition to aiding our lives, technology facilitates evil and extremist efforts—especially message-boards and other platforms that create communities of hate. So much about the show is about “influence” and “impression,” about how we are shaped into who we are, how we act, and what we promote (from our spiritual gods to our digital ones).

This is not to say that the show doesn’t have fun with its subject matter, either. While our overgrown and under-supervised technological culture can become the devil’s playground, it is primarily Evil’s playground. So much of the show plumbs the depths of online culture for fun; some of the episodes’ cases involve urban legends or even online creepypasta. Perhaps the show’s most alarming episode features a Bloody Mary-style game featuring an elevator which will take you to hell if you press the right buttons in order.

In this way, Evil represents the ways our questions about the metaphysical world appear in our own daily life–part of its central framing of a thematic tension between doubt and faith, and not just in religious contexts. Evil tends to a complicated web of questions about the good and the bad natures of both faith and doubt when taken to extremes. The series is also about temptation, and when it is right and wrong and ambiguous. But also, crucially, in asking what the devil looks like in today’s world, Evil also asks what God or a god might look like, and where that god might be found. To say that Evil encourages introspection is the understatement of the century.

Even considering my natural aversion to the topics it undertakes, I must give the devil its due and say that I have been continually impressed with Evil. It is consistently one of the smartest, boldest television shows I’ve seen in a while—meaningfully integrating a longstanding horror genre with crucial questions about life in our post-Trump America, a place where the seeds of evil have been planted and are waiting to be sown, en masse—a place with lots and lots of terrible cultural characteristics that should go rot in hell, once and for all.