–Featured photograph by Maggie Wrigley

My long love affair with Brooklyn began years back when I, a Harlem born and breed kid, took acting classes at a storefront drama school in “do or die” Bed-Stuy back in the blaxploitation ‘70s when I was a 12-year-old kid who thought I might get hired to play Diahann Carroll’s son or perhaps perform the nice kid part before the protagonist became a ruthless criminal. I missed the call when they were auditioning kids for The Education of Sonny Carson, but I did write a play about a plane being hijacked for the class to perform, which put me on different creative path.

Years later, in 1981, I attended the Brooklyn Campus of Long Island University (LIU) in Fort Greene across the street from Junior’s Restaurant. After exiting the subway station at Dekalb Avenue, I stood on the corner and simply absorbed the landscape as my soon to be fellow students filed into the building. Where I was stood, I later learned, was the cafeteria and gym. That section of the school used to be the Paramount Theatre where Frank Sinatra once sang.

Soon after orientation and joining the staff of the school paper, I began exploring the borough with my new friends Michele Vernon and Lourdes Martelly, classmates who introduced me to the wonders of Albee Square Mall, the Brooklyn Heights promenade, Christie’s Jamaican Patties on Flatbush Avenue and the massive wonderland of the Grand Army Plaza library. Down the block was the Brooklyn Museum. Though I’d never been inside, I knew it well from seeing it as the heist location in The Hot Rock, a 1972 crime flick starring Robert Redford based on a book by Brooklyn-born novelist Donald E. Westlake.

I was an English major who’d already decided that I wanted to be a writer. Part of the reason I chose LIU was because of the English department headed by Martin Tucker, who also edited Confrontation literary magazine. One evening I visited Mr. Tucker’s office, and he introduced me to writer Sol Yurick, the former social worker who wrote the novel The Warriors. Though I was a fan of the Walter Hill film about a Brooklyn street gang trying to get from the Bronx to Coney Island while battling their rivals, I hadn’t yet read Yurick’s book. Still, I was impressed with meeting a “real writer.”

Even though Brooklyn was full of writers, most magazine and newspaper articles of that era perpetrated the myth that pens dried-up and typewriters stopped working once you crossed the Brooklyn Bridge. It was during that time I started reading a few other Brooklyn-based books including Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby Jr., The Assistant by Bernard Malamud and Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall as well as essays by Norman Mailer, Pete Hamill and Truman Capote.

Capote’s essay “A House on the Heights” opened with, “I live in Brooklyn. By choice.” It was in that piece where Capote expressed his love for his Brooklyn Heights house at 70 Willow Street as well as documenting other writers (Hart Crane, Richard Wright and Carson McCullers) who once called the borough home. Back when the concept of “cheaper rents” actually existed, Brooklyn was a respite for many creative souls just trying to get by. Capote’s catty opening sentence was directed at those snotty folks who looked down their nose at the borough as though Manhattan was the only landscape that mattered.

Beginning freshman year of college, my new buddy Jerry Rodriguez adopted me as his little brother. Jerry was studying to be a filmmaker, but he also drew really well. He and I worked briefly on a comic strip for the school paper. The strip ran for two weeks, but our friendship lasted for twenty-seven years.

I spent many hours taking the D train from 145th Street to his apartment on Cortelyou Road. Jerry was one of the first people I knew who had a VCR and we spent many days at his place watching movies. A big fan of various screenwriters, he schooled me on the works of William Goldman, Paddy Chayefsky, Paul Schrader and Lawrence Kasdan. Body Heat, written and directed by Kasdan, was one of Jerry’s favorite movies, and one that he introduced me to.

Though I’d seen noir films before, it was from watching Body Heat that I became aware of the cunning concept of the femme fatale. I recently revisited the film and smoking hot fatale Matty Williams (played with deep-voiced seduction by Kathleen Turner) two years back as inspiration for “Haunt Me,” a tale I wrote for the Maxim Jakubowski edited The Book of Extraordinary Femme Fatale Stories.

When a video store opened on Cortelyou Road, a couple of blocks from the subway station, it became like a second home for us. Through our love for the crime films of the ‘70s and early ‘80s, we also began renting black and white noirs. A few doors down from the video store was a used book shop where there were countless paperbacks, a cool black cat that prowled the stacks and an overweight owner who grunted when he spoke, but didn’t bother us otherwise. It was there where I came across a beat-up copy Street of No Return by David Goodis. “Only the ruthless survive River Street where concrete ends and jungle begins,” read the copy printed on an illustrated cover.

Goodis’ brilliantly bleak book told the tale of a former crooner named Whitey (à la Frank Sinatra) who, seven years before, loved the wrong woman and was severely punished by her gangster boyfriend who cut his throat. No longer able to sing, he dwells on skid row in Philadelphia with the rest of the drunks and derelicts until something happens that triggers a very long night involving gangsters, a beautiful woman and a race riot.

Plunging into the darkness, Whitey’s life becomes yet another long descent into hell. The characters were scary and sorrowful, tough guys, dolls and drunks whose nuances Goodis captured perfectly, pulling the readers down deep into their bleak, complex and tormented lives. When I finished that hardboiled delight, I lent it to Jerry.

Weeks later, I was over the house and noticed that the book was all marked-up, chucks of text highlighted in yellow and pink. “What the hell did you do?” I asked. Jerry explained how he’d decided he wanted to adapt the novel into a screenplay and make it into a film. He was serious too. Though I was pissed that he messed up my book, which I later replaced with the Black Lizard reissue, I was pleased that Jerry liked Goodis as much as I did.

Jerry’s script was cool, but his version of Street of No Return never happened. Years later, exiled filmmaker Sam Fuller made the movie in France. When Street of No Return was finally released in the States in 1991, we went to see it at the Film Forum and were greatly disappointed. He’d updated the book, turned the crooner into a rock star and the movie just looked fake and sad. “My movie would’ve been better,” Jerry said as the closing credits scrolled up the screen. To this day, I believe it would have been.

In 1984, after three years at LIU, Jerry and I both dropped out. Through his sister Janette, we got jobs at Auburn Homeless Shelter, located in a former hospital behind Fort Greene Projects. Working the midnight to eight a.m. shift, there were twenty of us. Our Puerto Rican co-worker Gus swore the building was haunted and came to work wearing colorful Santeria necklace beads for protection. Truthfully, I felt the presence of spirits at Auburn, but they never seemed evil to me.

Jerry and I were at Auburn during the height of the crack era, walking through the infamous Fort Greene Projects to get there. Every night I passed the drug dealing corner boys, chain snatchers and the wild dudes who cheered at hip-hop shows when a rapper asked, “Is Brooklyn in the house?” Unlike the trendy Brooklyn Boheme depicted in Nelson George’s 2011 documentary, much of what I saw wasn’t as charming or romantic. In the mornings we sometimes went to Jerry’s sister’s place for breakfast. No one made banana pancakes as good as Sylvia.

Still, on my days off, I couldn’t stay away from Brooklyn, going out for drinks at Frank’s Cocktail Lounge on Fulton Street, dating a woman who lived on Lafayette Ave, across the street from the Brooklyn Academy of Music, puffing blunts in Brownsville rap ciphers with homeboy Gregory and hanging with my bro Stacy outside Farragut Houses projects.

A decade later, when I first met Lesley Pitts, the woman who would soon be my girlfriend, she lived in a studio apartment on South Oxford, a few blocks from LIU, but she wasn’t happy there. “I didn’t move to New York to live in Brooklyn,” she complained. When we decided to move-in together, we got a place in Chelsea, and Lesley only went back to Brooklyn for backyard barbecues and house parties. In 1996, when we celebrated our fifth year together, I suggested we try buying a place in Fort Greene, but she simply looked at me like I was crazy.

However, after her sudden passing from a brain aneurysm on August 3, 1999, I was in a jam. I couldn’t afford our Chelsea apartment by myself, but thought it would take me months to find a new place. Fellow writer and good friend Amy Linden came to the rescue. She was the one who discovered that the mom of our mutual friend Corey Glover, the lead singer in rock band Living Colour, had a place available in Crown Heights. One afternoon in September, he picked me up from the corner of 22nd Street and 8th Avenue, and drove me to his old neighborhood.

Forty-five minutes later we arrived at 201 Brooklyn Avenue between Eastern Parkway and Union. In a 2020 interview with Consequence of Sound, Corey talked about his mom and the neighborhood where he was raised. “My mother was born in a town called Meigs in Georgia and my father was a bastard child — he and his 15-year-old mother had to leave South Carolina because she was pregnant with him so they moved around and then moved to Brooklyn. I have an older sister and an older brother, my sister was born in Harlem and then my brother came around and they were like, ‘Oh this is too many people,’ so they tried to find somewhere to live, so they moved to Crown Heights.”

According to city records, Mrs. Glover’s two-family house was built in 1901. Ninety-eight years later, though the hallways were dimly-lit, the building itself was well kept; I felt the charm and warmth of the old house the moment I walked through the front door. Mrs. Glover lived next door, but entered her place through a separate entrance. Walking to the top floor, I was impressed by the massive living room, which would become my main sleeping quarters and office. We connected and she instructed me to call her the following week. For the next seven days I was worried, but all went well. “I still have some work to do to the apartment, but you can move in next month if you’d like.”

Beyond excited, I called the movers and by the second week in October, they were loading boxes and furniture onto the truck. From the first day I moved in, I’d spent hours looking out of the living-room window, surveying the usually quiet block and watching the daily activities across the street at the Church of St Mark, whose bells tolled every half-hour. The sound was annoying at first, but soon the ringing became just another part of my day. Some afternoons I’d glance across the way and witness a beautiful wedding, a crowded Christening or a teary-eyed funeral.

Brooklyn Avenue was a quiet block where most of the residents were African-American, West Indian and Hasidic Jews. More than a few had lived there for decades. The neighborhood was filled with mom-n-pop shops and West Indian restaurants where six dollars bought me a meal of curry chicken, rice-n-peas and cabbage that I could eat for two days. For the first time since my childhood days uptown I was part of a community where neighbors greeted one another, ran errands for each other and, on nice days, chatted on the stoop.

At that time I preferred writing in the middle of the night, wide awake typing and sipping Café Bustelo as the rest of the world slept. It was in that apartment where I began writing short fiction. Though I’d written hip-hop journalism for the past decade, writing stories was another thing altogether. One night in the spring of 2000, as I sat hunched over the computer working on the noir erotica tale “Movie Lover” for the first Brown Sugar anthology, a giant bat flew through the open window.

As the creature beat its wings wildly, I screamed like a little girl, ran out of the room and slammed the door behind me. The fact that the living-room had a door was a good thing. Though I hardly slept, the following morning I found a rusted curtain rod and carried it in my hand as I went looking for the vampire I was certain was going to suck my blood. Thankfully, the bat was gone, but I couldn’t help but think it was an omen. Perhaps someone had put a curse on me. I asked my Dominican friend Patricia Santana, who replied, “I think it means you need a screen.”

My friends in the neighborhood varied between those I’d known for years and new people who’d soon become family. Jerry lived on Bedford Avenue and publicist Charlotte Hunter, who I’d met in the 1980s when she worked at Def Jam doing press for LL Cool J and Public Enemy, stayed a few blocks from him. A couple of subway stops away was my brother from another Scotty Boyd, the only one of my male friends who had a son. The boy’s name was Cooper and occasionally I went with Scotty to watch the kid’s little league games in Prospect Park or to pick him up from school.

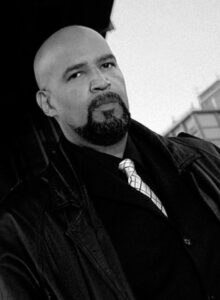

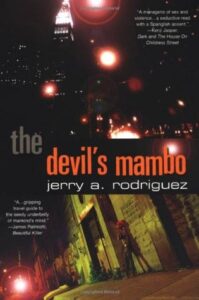

Author Jerry Rodriguez.

Author Jerry Rodriguez.

In the summer of 2000 I met journalist Tomika Anderson. She lived two blocks up Eastern Parkway, and her 6th floor apartment soon became my second home. Tomika, along with fellow writers Asha Bandele, author of the acclaimed memoir The Prisoner’s Wife, crime writer Kenji Jasper, journalist/editor Miles Marshall Lewis, fashion journalist Nicole Brewer and budding scribe Brook Stephenson, were my constants that were always fixing meals, mixing drinks, rolling joints and offering emotional support when days were dark. We were a community and those years were my Harlem Renaissance.

Mrs. Glover was often outside sweeping in front of the house or sitting on the stairs reading the Daily News. Often we talked in the mornings and she shared both her personal history as well as that of the neighborhood. There were days I spent with Mrs. Glover on that stoop, including 9/11.

When the first plane hit the World Trade Center, I was in the house and heard it mentioned on Howard Stern. I watched a little bit of the news and was surprised at the size of the hole in Building One. Minutes later, I was downstairs and headed to the bodega to buy a breakfast sandwich. Mrs. Glover asked me to pick her up a half gallon of milk. While I was inside the store watching the television screen with the Pakistan counter man, we saw as the second plane came around and hit the other building.

“What the hell!” we both screamed. Shocked, I stayed in the store longer than usual. By the time I got back to the house, Mrs. Glover was sitting on the steps shaking her head. She told me that her oldest son Tommy had called her to say he’d witnessed the crashes from the Brooklyn Heights Promenade. “It’s an attack,” Mrs. Glover said, her voice trailing off.

Another sorrowful day was when our next door neighbor James E. Davis, a respected Councilman and community leader, was killed inside City Hall, on July 23, 2003. When I heard the NY 1 teaser about “a councilman killed at City Hall, I thought, “Please Lord, don’t let it be James.” Of course, by then, it was too late for prayers. His murder at the hands of friend and political rival Othniel Askew, a closeted gay man who believed Davis was going to out him.

Since Davis was a Councilman, he and his guest Askew weren’t made to go through the metal detectors. Once they passed security, Askew killed Davis, and he too was slain by a young cop. The incident shook me. I didn’t know Davis well, but saw him often in front of the house, always sharply dressed in a suit and polished shoes. We had a few conversations and, though he invited me to a few of his events, programs and marches, I had no interest in politics.

The following morning, as I returned from the store with coffee and newspapers, I saw Mrs. Glover on the stoop; I sat on her steps, opened the New York Times to the story about James and read aloud: “The main session was about to start…Councilman Davis, a former police officer who led a community group called Love Yourself: Stop the Violence, had planned to introduce a resolution trying ‘to prevent violence in the workplace.’ Then Mr. Askew drew a .40-caliber silver-colored pistol and started shooting.” Mrs. Glover shook her head and muttered, “It’s always something, always something.”

Always kind and a protector of sorts, Mrs. Glover understood me. As a freelance writer, I wasn’t always flush and sometimes the rent was late, but I didn’t have to hide or duck her out. Within the month I would get the money and I made sure she got paid before the phone company or Con Ed. Five years went by before she raised my rent, and that was only after my friend Jerry Rodriguez, along with his suitcases and ferrets, moved in during the summer of 2005. I gave him the bedroom since I’d always slept in the living room.

I was shocked when I saw the battered, marked-up copy of Street of No Return on his bookshelf. Twenty-one years later and more than a few moves to apartments across the city, and he still had that damn book. “More like book of no return,” I snapped, and we both laughed. Two decades before we had no idea how much David Goodis’ losers, drunks and whores would inspire our own writings, but looking back his influence could be seen in both of our work. After Jerry got settled I turned him on to books by Gary Phillips, Jason Starr and Ken Bruen, all three who later became his friends when they met at Bouchercon in 2007.

Jerry had cancer when he moved in with me. It was in remission, but came back a year later. He refused to let that get in the way of his life as he continued to work a full time job and rewrote his noir novel The Devil’s Mambo. The book was published in 2007, from Kensington Books. Though I’d been helpful in him finally securing a book deal, he too helped me when I was began writing more genre fiction.

The first time was when I was working on my futuristic action story “The Whores of Onyx City,” that was published in the superheroes of color book The Darker Mask (2008), edited by Gary Phillips and Christopher Chambers. Jerry helped with the structure and tone, which I was trying to write like a cyberfunk sci-fi ‘80s comic book tale mixed with Blaxploitation. “Stop being so serious with it,” he advised. “Have fun with it.” Those magic words were what I needed to push through and complete the story.

We spent many hours together puffing weed, watching movies and discussing writers, writing and life. In 2007, a few days after Christmas, Jerry had gotten sicker and went to live with his sister Janette. He also completed a second crime novel Revenge Tango, which he edited on his death bed. The book was published in May, 2008. The following month Jerry died on June 22, the day before my birthday.

It was around that time that I began to notice a change happening in the neighborhood. There were more police on the streets and the Middle-Eastern owned bodegas began to clean-up. Installing new counters, shelves and refrigerators, the usual Arizona’s drinks, sodas and various sugary drinks were stacked beside bottles of Wolfgang Puck gourmet iced coffee and other designer beverages with fancy labels.

“You know that shit isn’t for us,” I said snidely to my friend Nicole. It hurt my feelings that it took an influx of young hipsters for these stores to undergo makeovers. Did the original residents of the neighborhood not deserve new linoleum flooring, clean shelves or seasonal beers?

“I knew things were changing when they closed the drug store on Nostrand Avenue and opened a Dunkin’ Donuts,” Tomika told me later. “I began to notice that the some of the patrons were these entitled millennial hipsters, arty types with long hair and shaggy beards. Some were cool, others were very rude. It never seemed that they wanted to be a part of the community, but just trying to take it over.” The “pilgrims,” as I thought of the (mostly) pale-faced strangers I passed more often while walking down Eastern Parkway to the Kingston Avenue subway station, were moving into the neighborhood as more familiar faces began to fade from the landscape.

Some of the newcomers tried to be friendly, with their forced smiles and anxious expressions, but others ambled by with their heads held high and simply ignored the natives that they knew would soon be gone. A few years before, I’d seen the same kind of behavior from the newcomers in Park Slope, Williamsburg, Carroll Gardens and Fort Greene; the streets of Crown Heights were just the latest conquest in a long line of takeovers.

When I was a child growing-up in New York, many neighborhoods were “melting pots” of various races and creeds coming from working class roots. The city was a different place back then, an affordable metropolis where jazz musicians and school teachers, ballet dancers and construction workers, publicists and plumbers might all live in the same building. It was a city where one could be whomever one chose, but could still afford to pay the rent without having to sacrifice food.

However, with city politics becoming more about the wants of businessmen over the needs regular people in our communities, money talked and the used to be lower-middle class were expected to walk. When people hear lifers like me talk about the way New York used to be, they think we’re urban romantics bemoaning the removal of crime and grime, but our real beef is the loss of community and character that was once so strong. What was once civic pride has transformed into entitlement that feels race-based when people can’t do simple things like say “good morning” or “thank you” when a door is held for them.

After Mrs. Glover’s death in 2009, I knew things would be changing. Shortly after the funeral, her granddaughter informed me she was raising my rent by an extra two hundred dollars a month. I simply laughed. “I can hardly afford to pay you now,” I replied, “what makes you think I can afford that?” Thankfully, she decided to raise it gradually. Meanwhile, across Eastern Parkway, Asha was dealing with similar issues with her landlord, who raised her rent forty percent one year and basically kicked her out the next.

“I’d lived in that apartment for twenty years,” she told, “and one day the landlord told me he wanted to renovate the apartment and he wanted me to leave. I raised my daughter Nisa there; I’ve had poetry readings and writer’s workshops there; there was always a sense of community there, but, as we can see, our communities are disappearing.”

2011 was perhaps my most noir year when in November I almost became one of those dead guys who know Brooklyn, as Thomas Wolfe so elegantly put it in his 1935 New Yorker story. Coming home the week before Thanksgiving, I was shot three times in front of my building in a case of mistaken identity. Though it’s hardly anything to brag about, I don’t know any other crime writer who has taken a few bullets for real.

Between the non-stop gentrification and the steadily increasing rent the following year, in 2012 I decided it was time to say goodbye to Brooklyn. I was blessed when an old editor and friend Sheena Lester, who lived in Philadelphia, told me she was looking for a housemate. I leapt at the opportunity. I knew very little about the city except it was the hometown and creative turf of a few of my favorite artists including soul songwriters/producers Gamble & Huff, rapper Schooly D. and writer David Goodis.

In the years since I left New York, I’ve returned to Crown Heights often and am always shocked by how different it is each time. A luxury high-rise opened on the corner of Franklin Avenue, the gas station on Bedford Avenue has been torn down to make way for a new office building and many of the family-run West Indian food shops have been converted into trendy bars and restaurants with overly cute décors, overpriced drinks and names I can’t pronounce.

In November 2019, after I journeyed to the city to celebrate Nicole’s birthday at a tiki bar on Nostrand Avenue, I walked up to my old Brooklyn Avenue block. Buzzed from frozen drinks, I stared upwards at the windows of my former apartment. The block and building looked the same, but in my heart and mind, I knew how much had changed.