Who could have known that newspaper comic strips and crime stories, including noir, were a match made in heaven?

Newspaper comic strips are an artistic genre that’s largely forgotten now. The strips that remain are for the most part humor strips like “Garfield.” A handful of dramatic strips are still published.

But serial dramatic strips were once a staple of the newspaper comics page. Many of them were soap opera-ish strips like “Mary Worth” and “Apartment 3-G.” To say that drama strips were slow moving is an understatement. I wish I could remember who joked that they came back to read “Apartment 3-G” after decades away and the caption read, “Later that afternoon …”

But that deliberate pace – well, maybe not quite that deliberate – was perfect for teasing out a good crime storyline. And crime and noir look awesome in black and white newsprint.

The best-known of the newspaper crime strips is probably “Dick Tracy,” which debuted in October 1931 and is published to this day. Chester Gould created the crimefighting detective, his colorful antagonists and his high-tech tools, including the two-way wrist radio. Gould drew the strip until 1977. That’s an unbelievable span of time: translated into cinematic terms, that’s from the early days of talking movies to “Star Wars.”

And speaking of cinematic: “Dick Tracy” made the leap to the movies. (Not to mention radio and comic books, so we won’t mention those.) Movie serials and features followed the strip, peaking in 1990 with director and star Warren Beaty’s lavish, primary color big-screen treatment that brought to life the cast, including the strip’s outlandish villains like Flattop and Pruneface. Meant to capitalize on the 1989 “Batman” movie, “Dick Tracy” was good but not an instant classic.

The bizarre visages of the Tracy villains, the sharp-chinned detective himself and the bold black-and-white – and later color – graphics leapt off the newspaper page. It was the retro-futuristic police tools, like the wrist radio, that helped keep “Dick Tracy” in the public consciousness for so many decades.

As big as “Dick Tracy” was on the comics page, though, my favorite was an enduring and very crime-movie-ish strip that ran for many decades.

The dynamic duo of newspaper crime strips

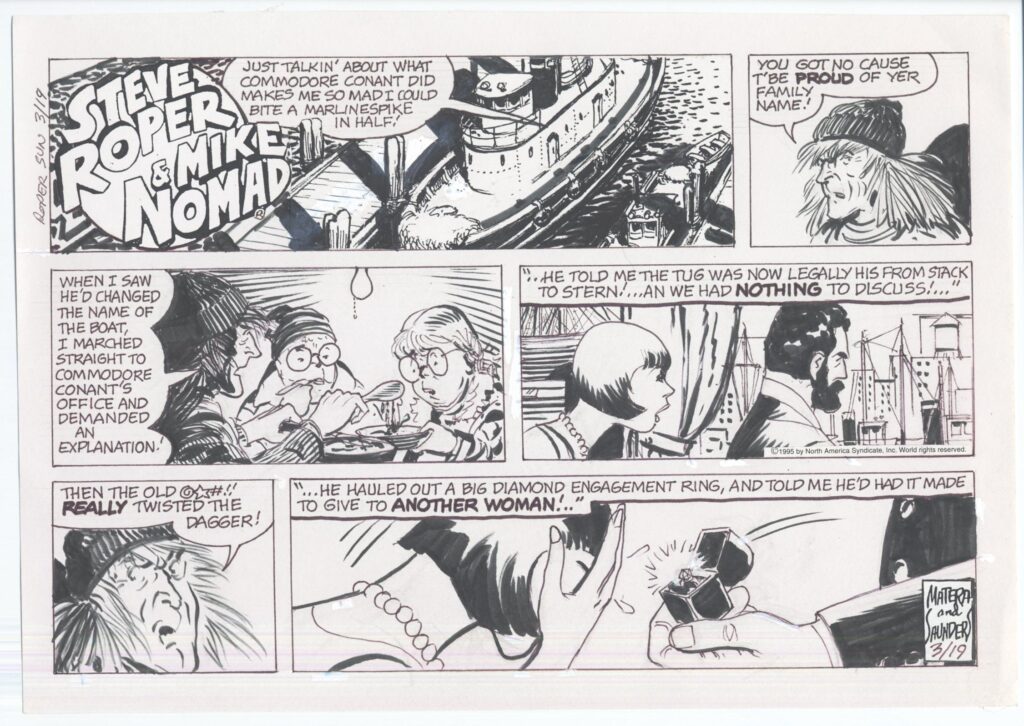

I still remember being startled, sometime in the late 1990s, to be on a road trip and picking up a copy of a small local newspaper, checking out the comics page and seeing a “Steve Roper and Mike Nomad” strip. The comic had disappeared from my local newspaper years before, and I had no idea it was still being published anywhere.

Like many serial drama strips, the Roper and Nomad strip had been dropped from many newspaper pages. My local paper dropped Roger and Nomad in early 1981 to make way for, believe it or not, a “Dallas” strip, based on the popular TV show.

Complaints rolled into the newsroom, however, and the editors announced in February 1981 that Roper and Nomad would be reinstated to the comics page. Sacrificed to bring back Roper and Nomad? A “Donald Duck” strip.

My paper wasn’t the only place where uproar followed the end of Roper and Nomad. In a 1991 Cox News Service article, Keith L. Thomas – writing about a nine-month hiatus for “Calvin and Hobbes” – noted other newspaper comic strip controversies and said that when the Washington Post had recently dropped dramatic strips like “Steve Roper and Mike Nomad” and “Mark Trail,” the newsroom received more than 15,000 calls and 2,000 letters.

So what the heck was the fuss about?

Like a number of comic strip series, “Steve Roper and Mike Nomad” began life under another name. (Remember, Popeye started out in a strip called “Thimble Theater,” but the sailor man grew in popularity and eventually roughhoused his way into the title.)

“Big Chief Wahoo” debuted in 1936 and featured as its title character a horribly stereotypical Native American. A humor strip at first, the comic created by writer Allen Saunders began to feature more serious storylines and, in 1940, introduced a photojournalist, Steve Roper. As Roper fought spies during World War II, Wahoo became nothing more than his sidekick. By 1944, Roper’s name was in the title and by 1947, Wahoo was gone, according to Toonopedia. Roper morphed into a full-time journalist, a job that put him in many global hotspots.

Mike Nomad was introduced to the strip in 1956 as a two-fisted adventurer not unlike the Race Bannon character of the later animated series “Jonny Quest.” Nomad’s name eventually joined Roper’s in the title and Nomad – a tough guy with a gray flat-top – became the dominant figure in the strip.

The strip had echoes of classic adventure strips like Milton Caniff’s “Steve Canyon” and “Terry and the Pirates,” but Roper and Nomad were usually firmly grounded. But they were not provincial in the sense of staying put. The protagonists were globe-trotting investigators.

It became common to see Nomad, white hair (eventually, as he aged) gleaming and cigarette dangling from his lips, standing in a shadowy alley or doorway, in Chinatown or in China. Nomad worked as a cab driver, oil rig jockey and truck driver, blue collar professions that let him mix with dangerous types but still have dealings with the elite. And always, always, was Nomad willing to step in when a bad guy tried to intimidate a woman or bump someone off. (Sometimes he stepped in a little reluctantly.)

By 1989, Nomad – after decades of dangerous adventures – had become a private investigator. The job eventually solidified the noirish stories and dialogue that had always been a part of the strip. When a woman he’s dating suggests marriage to solve a financial problem, Nomad replies, “No dice, baby. When I let ‘em hang the double harness on me, it won’t be to save a few lousy bucks.”

Confronted by guard dogs, Nomad has the same attitude. A companion asks if they should take a chance that the dogs might be fierce, Nomad replies, “What can we lose – except a leg or two?”

Roper – who was an irregular presence in the strip as the character was allowed to age – and Nomad permanently retired in 2004, or so it seemed. They reappeared in the modern day “Dick Tracy” strip in 2019.

Other crime comic strips came and went, but none had quite the staying power of “Dick Tracy” or “Steve Roper and Mike Nomad.”

Also-rans – and a legend

Another crimefighter from the comics who started out as a supporting player, like Steve Roper, was “Captain Easy,” who initially was a sidekick to “Wash Tubbs.” The character appeared from 1929 to 1988. Easy was a soldier, soldier of fortune and eventually private detective.

“Dan Dunn” was such a “Dick Tracy” imitation that to the untrained eye, it’s hard to tell them apart. The Dunn strip ended in the middle of World War II.

“Charlie Chan” is remembered today, if at all, as a cringeworthy stereotypical Chinese-American detective, played at the movies by white actors. Writer Earl Derr Biggers created the character and based Chan on a real-life detective in Hawaii, Chang Apana. Chan solved mysteries beginning in books and continuing in movies, radio and comic strips, which were canceled after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Chan was of Chinese descent and the character was based on a Hawaiian, so the cancelation seemed to be for the wrong reasons.

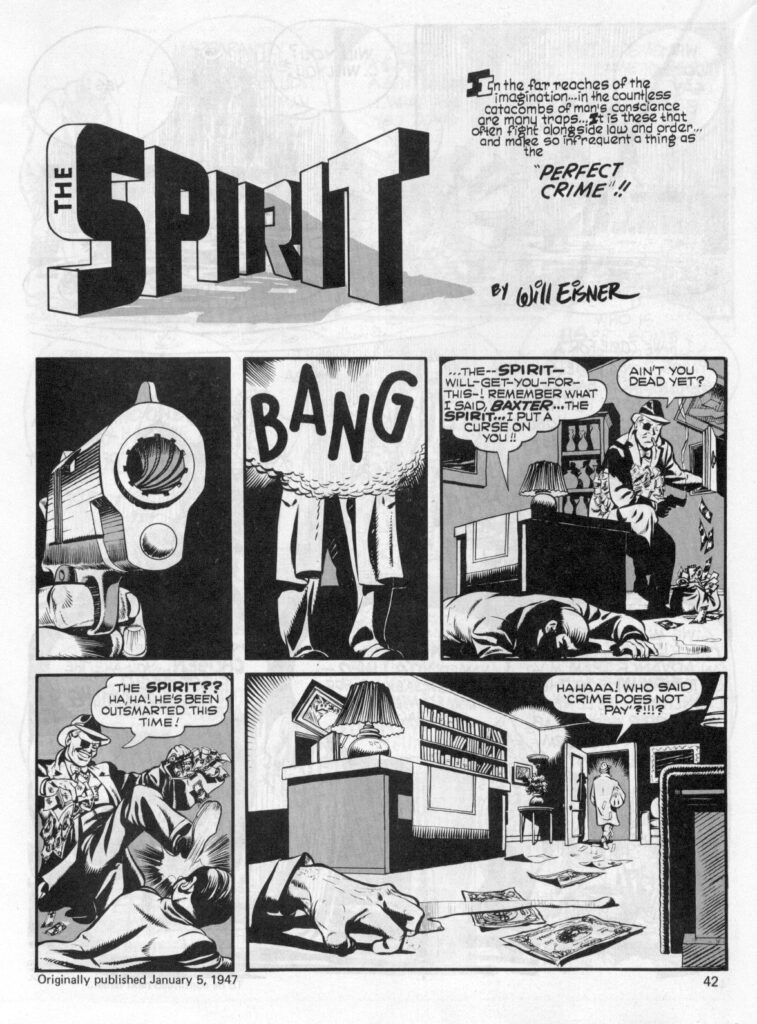

Racial stereotypes were no stranger to “The Spirit,” Will Eisner’s beautifully rendered noir story of an assassinated cop, Denny Colt, who returned to the streets to fight crime. “The Spirit” was different because it began life, in 1939, as a comic book inserted into newspapers. Eisner’s art is still legendary. Until its run ended in 1952, “The Spirit” set the standard for unique composition and when the stories were reprinted beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, they felt fresh all over again.

Perhaps no newspaper strip so beautifully captured the world of black-and-white crime as “Rip Kirby.” Credited to comic strip masters Alex Raymond (“Flash Gordon”) and Ward Greene, the strip followed the adventures of the titular private investigator. The strip ran from 1946 to 1999, much of that time with the art of John Prentice. The art throughout the series is a delight: the stark black and white emphasized the beautiful character design and costumes. Kirby, who like Steve Roper often smoked a pipe, seemed more professor-like than tough guy. But there was plenty of action and gunplay in the strip.

“From the beginning, the style of Raymond’s new strip was influenced by the latest trends in magazine illustration,” according to Brian Walker’s mammoth history of the genre, “The Comics: The Ultimate Collection.” “Glamorous women, realistically rendered settings and understated action sequences complemented the strips.” Raymond was, tragically, killed in a 1956 auto accident and Prentice took over.

It’s possible there’s no stranger pedigree in newspaper comics than “War on Crime,” which appeared in newspapers from 1936 to 1938. The strip was not a serialized treatment of a dashing hero like Dick Tracy or a pugnacious adventurer like Mike Nomad. Instead, the strip was co-created by J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, and was intended to improve the reputation of the agency and emphasize it was a crime-fighting organization with many experienced investigators who were above reproach. Hoover approved the stories that were told.

By taking the fact-based approach of basing the strips on the battles against real-life crime figures like John Dillinger, “War on Crime” was a victim of the FBI’s success, according to Comic Book Plus. The strip eventually ran out of true crime stories to adapt.

Some serial drama strips, including crime strips, continued for decades after the 1950s, but it was in that decade that were overshadowed by the humorous “gag-a-day” strips. “The Comics” book summed up the thinking.

“Editors became increasingly convinced that newspaper readers no longer had the patience to follow plotlines that took weeks to develop when they could watch a complete episode on television in thirty minutes or an hour.”

Milton Caniff disagreed.

“The best gag strip in the world in terms of just plain acceptance is ‘Blondie,’ and you can miss it any day,” Caniff said. “But assuming you’re hooked, you can’t miss (soap-opera strip) ‘Rex Morgan’ because every day there’s a push forward of the story. If you miss it, you’re penalized; you lack some significant bit of information about the story.”

If not for the end of most crime comic strips, who knows how many more schemes could have been uncovered by Rip Kirby or how many crimes could have been avenged by the Spirit, or how many more thugs could have gotten their comeuppance from the fists of Mike Nomad?

___________________________________

Keith Roysdon writes about news and pop culture for several publications. His crime novel “Seven Angels” won the 2021 Hugh Holton Award for Best Unpublished Novel from Mystery Writers of America Midwest Chapter. Besides his freelance writing, he’s got several pieces of fiction in the works. The best part of writing is listening to music from the time period, so early ‘80s tunes are on heavy rotation right now as he works on a crime novel set in October 1984.