It’s safe to bet that most people reading this article are acquainted with the 1942 Warner Bros. picture Casablanca, and that a number of them (including yours truly) have watched said Humphrey Bogart/Ingrid Bergman romantic drama multiple times. But how many of you remember the 1955–1956 ABC-TV series that sought to capitalize on the film’s renown?

That Casablanca spin-off handed the Bogart-defined role of expatriate nightclub owner Rick Blaine (here renamed “Rick Jason”) to square-jawed actor Charles McGraw, who was perhaps best known back then for starring in film noirs such as Armored Car Robbery (1950) and Roadblock (1951). The Tuesday-night series portrayed Morocco’s largest city as a hotbed of Cold War espionage and even roped a few of the original picture’s supporting players into its plots. However, McGraw lacked Bogie’s engaging blend of cynicism and soft-heartedness, the show never firmly rooted itself in Moroccan culture, and Casablanca was cancelled after just 10 episodes.

Perhaps its lone enduring claim to fame is that it represented one “spoke” in what was evidently the first “wheel series” in American TV history: Warner Bros. Presents.

Boob-tube viewers of the ’50s were familiar with “anthology series” such as The Philco Television Playhouse, Four Star Playhouse, and The United States Steel Hour, all presenting (primarily) one-off yarns under a collective, or “umbrella,” title. Warner Bros. Presents, though, was different. Not only did that 60-minute telecast mark a powerful Hollywood studio’s initial foray into TV production, but it offered a trio of continuing dramas rotating weekly in a single timeslot. Casablanca was one, leapfrogging on Tuesday nights with King’s Row (featuring Jack Kelly—later of Maverick—as a small-town doctor aiding his neighbors with their physical as well as moral dilemmas) and Cheyenne (with Clint Walker as a peripatetic cowboy hero dispensing justice across the Old West).

Unfortunately, those three shows were “written, produced, and edited on minuscule budgets at a frenetic pace unseen at the studio since the B-grade movies of the 1930s,” explains a piece on the Museum of Broadcast Communications website. Critics, advertisers, and viewers declined to be impressed. Cheyenne alone survived its debut year—and was then granted six extra seasons.

But the prime-time wheel series concept had charmed TV producers. It would become a staple of crime-and mystery-fiction programming for years to come.

* * *

Flashier and far more ambitious than Warner Bros.’ effort was The Name of the Game, a 90-minute NBC show introduced in September 1968. Conceived as “the first motion-picture series in television”—at a time when small-screen “movies of the week” were attaining popularity—it boasted a $400,000-per-episode average budget from Universal Studios (which produced it and so many other dramas mentioned here), making it then the most expensive TV program in history. The Name of the Game premiered almost two years after the airing of its pilot flick, 1966’s Fame Is the Name of the Game, which put forth Tony Franciosa as Jeff Dillon, a hotshot magazine writer in Los Angeles probing the putative suicide of a party girl. Supporting Franciosa’s suave “wonder boy of the publishing world” was Peggy Chan (played by Susan Saint James), a brainy, ambitious, and multilingual recent journalism school grad newly assigned to Dillon as his editorial assistant.

Amid the transition from Fame to Name, Peggy Chan was rechristened Peggy Maxwell, while Dillon picked up a pair of revolving rivals for the series limelight: Glenn Howard (erstwhile Burke’s Law star Gene Barry), the head of L.A.-based Howard Publications Inc., which owns the weekly periodical for which Dillon writes, People (so named half a dozen years before today’s People magazine reached newsstands); and Dan Farrell (Robert Stack), an ex-FBI agent—every bit as earnest as Eliot Ness, the Prohibition enforcer he’d portrayed on ABC’s The Untouchables—whose wife was slain during a botched meeting with an informant, and who’s now the senior editor of Crime, a further Howard property. For most of the next three years, those journalist-detectives would switch off weekly as the show’s lead, with the mini-skirted, go-go-booted, and ridiculously overqualified Peggy (promoted to research assistant) aiding and connecting them all.

This Friday wheel series assigned separate production units to each of its three principals (allowing for longer shooting schedules) and recruited a remarkable array of talent. Steven Bochco (later to help birth Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue) served as a story editor. Richard Levinson and William Link (fresh from creating Mannix) contributed scripts, as did Dean Hargrove (of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. fame) and Leslie Stevens (who’d given us The Outer Limits). Composer Dave Grusin supplied The Name of the Game’s jazzy signature theme. Marvin J. Chomsky, Boris Sagal, and Leo Penn all directed episodes. And the show’s guest stars included Anne Baxter, Ray Milland, Honor Blackman, James Whitmore, Janet Leigh, Broderick Crawford, Ida Lupino, Joseph Cotten, and Boris Karloff.

Early advertising for The Name of the Game promised tales drawn from “an adventure-filled arena of high- and low-level exposés, and the intrigues of nations and people.” Storylines involved crimes of myriad sorts (sports corruption, the illegal employment of prisoners as slave labor, embezzling televangelists), but also explored racial tensions, the sexual revolution, American counterculture, and even the search for a “lost” Shakespeare play at a spooky Virginia mansion (a rare inquiry undertaken by pretty Peggy, though Dillon subsequently snatched credit for her discoveries). The 90-minute format allowed scripts to go deeper than was typical for episodic television.

“The Name of the Game was so wonderfully experimental,” says Gary Gerani, a screenwriter and film historian currently at work on a documentary about composer Billy Goldenberg, who wrote music for this series. “It could give us an original musical matched to a murder melodrama one week, a science-fiction story the next. The show’s creative parameters were that expansive.” Take, for example, the third-season installment “L.A. 2017”—directed by a young Steven Spielberg—which imagined the urbane, playboyish Glenn Howard falling asleep behind the wheel of his car…and waking up 46 years later in a world with a toxic atmosphere, subterranean bunkers, and a United States literally owned by Big Business. Another late episode, “All the Old Familiar Faces,” had Howard trying to figure out who from his past was sending him death threats, while a “Greek chorus” of young men and women sporadically intruded into scenes, heightening tensions with their ominous songs.

Although this program was twice nominated for Emmy Awards in the Best Drama category (and Saint James hooked an Outstanding Supporting Actress Emmy in 1969), it was never a mammoth ratings hit. Nonetheless, as The Hollywood Reporter recalled in an excellent 2018 retrospective, “The Name of the Game became appointment television for the younger, affluent demographic that advertisers craved.” There’s no telling how long it might have run, had Franciosa’s “erratic behavior” during shooting not led to his firing early in season three. Other performers were enlisted as stand-ins for Franciosa, among them Robert Culp, Robert Wagner, Peter Falk, and Suzanne Pleshette, who—in a poignant episode titled “A Capitol Affair”—played a savvy reporter tasked with profiling an increasingly vicious Washington, D.C. gossip columnist. But Franciosa’s appearances had typically been the most watched, and his abrupt departure from the show helped deep-six its chances of renewal. The last new installment was broadcast in March 1971.

The Name of the Game, Gerani observes, “was unique, a late-‘60s gem that provided a creatively innovative window into that socially turbulent American era….[It] was relentlessly ‘now’: sexy, adventurous, intellectually audacious. Presenting classic white-male establishment figures like Barry and Stack as fighting liberals who had more in common with fresh-thinking civil-rights leaders and the drug culture than Jack Webb’s glowering old guard was nothing less than a mind-blower.” Despite some dated cultural references and wardrobe choices, the program holds up admirably even today. It’s surprising that it still hasn’t won a DVD release.

* * *

In the four years after The Name of the Game debuted, NBC launched five more wheel packages. Clearly, it had faith in this approach, which expanded the variety of individual shows the network could squeeze into its schedule and drew big-name stars leery of more onerous weekly series commitments.

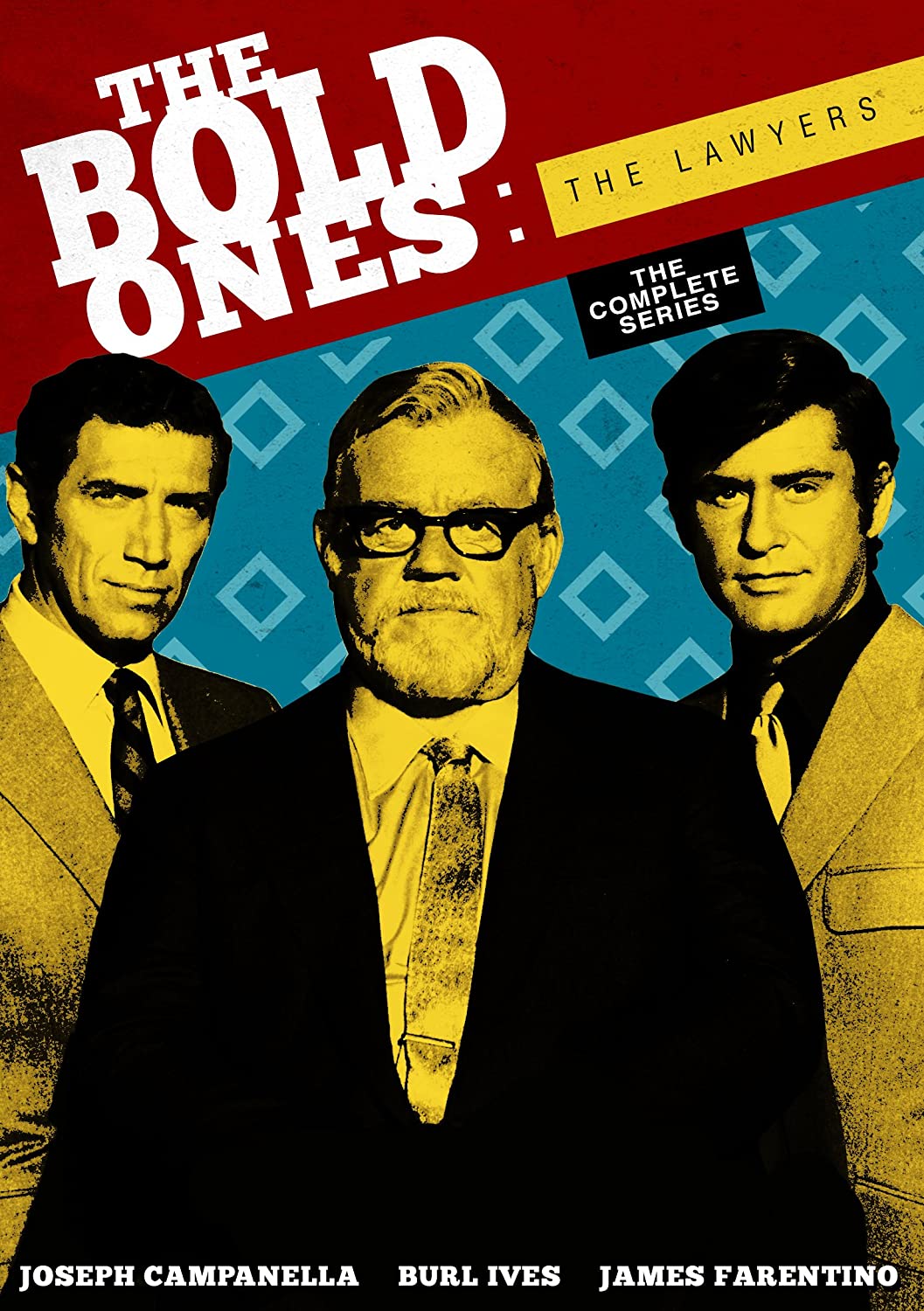

First to begin, in September 1969, was The Bold Ones. That umbrella title initially covered three distinct segments: The New Doctors, starring E.G. Marshall (formerly of The Defenders) as Dr. David Craig, a successful, middle-aged neurosurgeon whose staff included standouts Dr. Theodore Stuart (John Saxon), the chief of surgery at Los Angeles’ David Craig Institute of New Medicine, and internal medicine specialist Dr. Paul Hunter (David Hartman); The Lawyers, with singer-actor Burl Ives personating Walter Nichols, a shrewd, flamboyant L.A. defense attorney assisted in his diverse practice by two junior associates, brothers Brian Darrell (Joseph Campanella) and Neil Darrell (James Farentino); and The Protectors, featuring Leslie Nielsen as Sam Danforth, the conservative deputy chief of police in San Sebastian, a fictitious—and volatile—Southern California town, who clashed regularly with idealistic black district attorney William Washburn (Hari Rhodes). After a single season, however, The Protectors was axed to make room for The Senator, spotlighting Hal Holbrook as Hays Stowe, a highly principled, progressive member of the U.S. Senate who wasn’t afraid to put his reputation on the line in order to “do the right thing” (a quaint political notion nowadays).

What apparently linked these hour-long Sunday-night serials was their protagonists’ passion for bold action; Gerani calls this wheel “Son of The Name of the Game” in recognition of its topical storytelling. For instance, an early episode of The New Doctors (one of whose creators was Steven Bochco) focused on a sensory device intended to help blind patients “feel” images around them, while in another the Craig Institute risked losing a major grant rather than carry out an experimental heart procedure. The Protectors tackled civil-rights issues and drug abuse, though one installment dealt with a deadly virus threatening the local populace—imagine that! The Lawyers traded in controversial clients, from a physician charged with performing then-illegal abortions to Black Panthers embroiled in a confrontation with police. The Senator, certainly the most widely acclaimed of these spokes (it bagged eight Emmy nominations in 1971, and won five awards), found Stowe contending with air pollution, Native American rights, and the shooting deaths of two college students by National Guard troops during an anti-Vietnam War protest, a November 1970 storyline that echoed the “Kent State massacre” of six months before.

Yet good reviews couldn’t save The Senator; it was voted out after only eight installments. Season three of The Bold Ones was reduced to just The Lawyers and The New Doctors, with the latter alone re-upped for a valedictory year, until May 1973.

Meanwhile, in the fall of 1970 NBC premiered Four-in-One, an hour-long, late Wednesday umbrella series. It comprised a quartet of dramas with little in common save for the fact that they’d all derived from made-for-TV flicks. The programs didn’t even leapfrog each other, as had become traditional for wheel constituents; instead, six episodes of each were burned off consecutively. Viewers weren’t given enough time to attach to any one show before it yielded to the next in line.

McCloud was earliest out of the Four-in-One gates. It took its moniker from Sam McCloud (Dennis Weaver), a deputy marshal, late of Taos, New Mexico, who’d been assigned on a semi-permanent basis to the New York Police Department in order to study big-city law-enforcement procedures. This Stetson-hatted-fish-out-of-water premise greatly resembled that of Clint Eastwood’s 1968 film, Coogan’s Bluff –so much so that Coogan’s screenwriter Herman Miller was credited as McCloud’s creator. But Weaver made the part his own, chewing thoughtfully on matchsticks, brandishing his walnut-handled six-shooter against hooligans and, when necessary, chasing crooks through the streets of Manhattan on horseback. McCloud’s aw-shucks, seat-of-the-britches investigative style brought favorable results, but also rankled his boss, Chief of Detectives Peter B. Clifford (J.D. Cannon).

Following McCloud came San Francisco International Airport, which cast ex-Sea Hunt hunk Lloyd Bridges as Jim Conrad, the resourceful manager of Northern California’s largest and most hectic landing field. Amid the shrieks of departing jets and lost children, Conrad and his chief of security, Bob Hatten (Clu Gulager), negotiated crises such as an assassination attempt, a damaged plane needing to make an emergency landing, and mobsters endeavoring to flee the country. That melodrama ultimately gave way to Night Gallery, another innovative anthology series from quondam Twilight Zone host Rod Serling. While Twilight was more science-fiction oriented, Night specialized in tales of horror and the supernatural—black-magic spirit transference, the bizarre results of a doctor’s dabbling in hypnosis, a wife haunting the husband who’d murdered her, and more. Finally came The Psychiatrist, built around a young shrink, Dr. James Whitman (Roy Thinnes), laboring to help his patients—often young ones—cope with family, marriage, and assorted traumas.

God Bless the Children, the 1970 pilot for Thinnes’ show, had scored critical praise, particularly for guest star Pete Duel in his role as a junkie ex-con struggling to re-enter society. However, the series it spawned, together with San Francisco International Airport, was a washout. Four-in-One’s failure led to Night Gallery being turned into a full-fledged weekly broadcast (that continued until 1973), whilst McCloud found a new home as part of the best-loved wheel series ever: the NBC Mystery Movie.

* * *

There were essentially three types of wheel series: those like The Name of the Game (and lesser, earlier examples such as The Four Just Men and The Rogues), on which the protagonists more or less worked together; others, on the order of The Bold Ones and Four-in-One, that pooled disparate dramas under a unifying banner; and those that combined programs from one genre, even if they were otherwise unconnected.

The NBC Mystery Movie—with its haunting main title sequence and memorable, Henry Mancini-composed theme—fit that last category to a fare-thee-well.

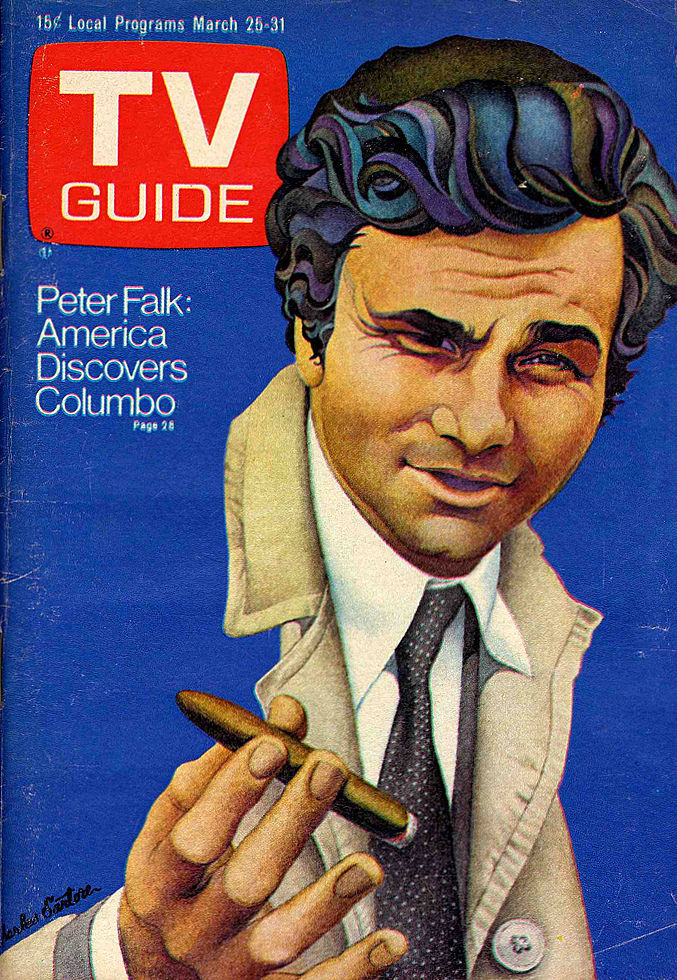

In its original 90-minute, Wednesday-night configuration, the Mystery Movie rotated a triad of character-rich crime-solving dramas. Joining McCloud was, first, Columbo, created by Richard Levinson and William Link, and based on their 1962 stage play, Prescription: Murder (later adapted as the figurative first pilot for this series). Levinson and Link acknowledged the influence of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Porfiry Petrovich on their Los Angeles police detective. But Peter Falk, who played the eponymous Lieutenant Columbo (no given name), set his homicide cop apart with a mélange of disarming and still-familiar idiosyncrasies: his ill-fitting suits and shabby raincoat, his dilapidated Peugeot, his never-seen-but-oft-mentioned wife, his cheap cigars, and his habit of asking “Just one more thing” before ending an interview. Those eccentricities lulled the upper-class killers he confronted (best-selling authors, psychiatrists, wine connoisseurs, pompous art critics, etc.) into believing Columbo could be fooled…right up until the moment when he sprung his trap on the villain.

Rather than stick to traditional “whodunit” storytelling style, which calls for a sleuth to ferret out clues and at length unmask a perpetrator, Columbo inverted that structure: the guilty man or woman was revealed upfront, and viewers then watched as Falk’s hero doggedly dissected the crime, slowly got inside the noggin of his quarry, and eventually beat him or her at their own game. (Only one episode deviated from that pattern.) Of course, all of this worked best when the murderer was ruthless and nearly as clever as Columbo, and when a ratings-grabbing trouper—be it Donald Pleasence, Jack Cassidy, Vera Miles, Dick Van Dyke, or Ruth Gordon—did duty as the “mouse” to Falk’s “cat.”

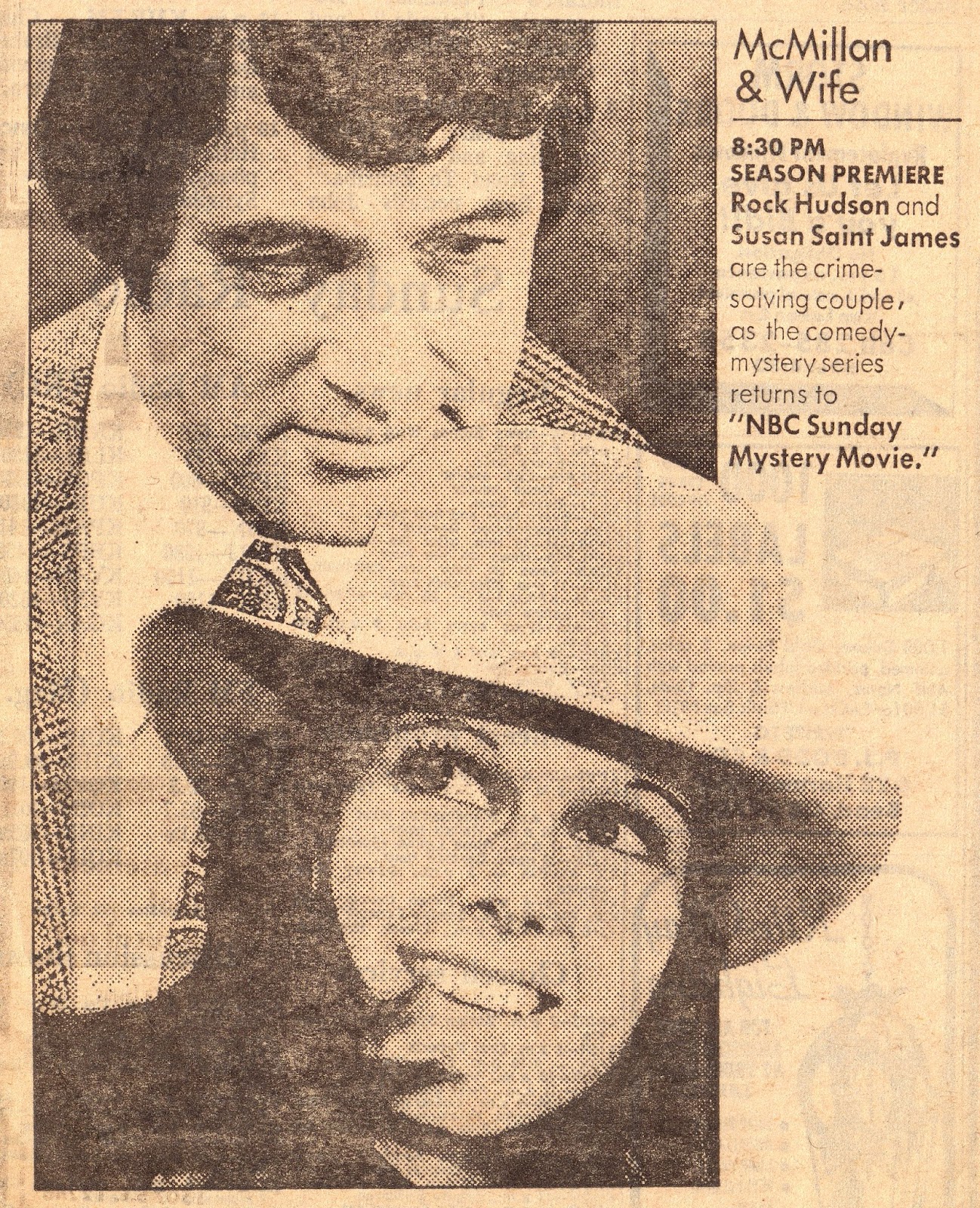

Rounding out this wheel was McMillan & Wife, a modern spin on the old Thin Man movies, but with far less tippling. Veteran leading man Rock Hudson portrayed Stewart “Mac” McMillan, San Francisco’s unusually hands-on police commissioner, while Susan Saint James returned to series TV as his much-younger, trouble-attracting, and occasionally brilliant spouse, Sally. The pair benefited from splendid on-screen chemistry and witty dialogue, and the cases they became involved in—with backup from Mac’s guileless cop assistant, Sergeant Charles Enright (John Schuck)—were classic-style puzzlers, escapist and with ample confounding ingredients. In one installment, a concert pianist’s stabbing raised questions about his ostensible history with Sally—who claimed never to have met him. Another found Enright as the “obvious” suspect in his ex-wife’s locked-room slaying, while in a third, a minor earthquake exposed an unidentified skeleton long bricked-up inside the McMillans’ chimney.

“It was the vivid, colorful, quirky central characters that initially drew me, and the rest of America, to the [Mystery Movie],” remembers author/screenwriter Lee Goldberg. “The characters were the shows…but we stayed because of the clever mysteries. It was a winning formula.”

So winning, in fact, that NBC swiftly sought to replicate it.

In September 1972, the “Peacock Network” moved McCloud, Columbo, and McMillan & Wife to Sunday nights, tweaked their umbrella title to the NBC Sunday Mystery Movie, and added a fourth component to the sequence: Hec Ramsey, starring Have Gun—Will Travel’s Richard Boone as a reformed gunfighter who’s acquired early forensic-science skills, and in 1901 signs on as the deputy police chief in an ambitious Oklahoma railroad town. Concurrently, the Mystery Movie’s previous timeslot was handed over to a new 90-minute teleflick block: the NBC Wednesday Mystery Movie.

Heading this second cluster was Banacek, featuring George Peppard as Thomas Banacek, a sophisticated but still tough, Polish-American freelance insurance investigator, based in Boston, who specialized in unraveling seemingly impossible, big-value heists. Each episode began with an audacious purloining (of a gold-bullion-filled armored car, a charter jet, a multimillion-dollar automobile prototype, a valuable religious artifact, or something else), and Banacek was left to figure out both whodunit and by what means he or she had accomplished the theft. Commencing next was Madigan, in which Richard Widmark reprised his street-savvy New York City lawman role from the gritty 1968 film of that same name—even though Dan Madigan had perished at the end of the big-screener. Miraculously resuscitated for this new Mystery Movie, Widmark’s detective sergeant went on to probe crimes in Gotham, but also in large European cities, where his hard-nosed tactics weren’t always appreciated. Completing this midweek roster was Cool Million, which introduced James Farentino as Jefferson Keyes, once a prized CIA operative but now a jet-setting private eye to the rich and infamous, charging a hefty $1 million per assignment.

That same 1972 season welcomed two other hour-long wheel series. Scheduled right after the NBC Wednesday Mystery Movie was Search, another Leslie Stevens-developed drama, centered on agents of a high-tech securities company who could locate and recover pretty much anything or anybody. Those alternating operatives—played by Hugh O’Brian, Tony Franciosa, and Doug McClure—remained in constant communication with a computer-stuffed mission control room, where technicians (led by Burgess Meredith) kept tabs on their health and movements via miniature telemetry units and cameras that the globe-trotting gumshoes wore either on rings or as medallions around their necks. Rolling out on Thursday nights, in the meantime, was ABC’s The Men, a rotation of three high-stakes espionage and crime dramas. Assignment: Vienna cast The Wild Wild West’s Robert Conrad as an American expatriate whose ownership of a bar in the beautiful Austrian capital supplied cover for his U.S. intelligence work tracking down international spies and criminals. In The Delphi Bureau, Laurence Luckinbill adopted the guise of a notably un-heroic research expert with a photographic memory that made him a valuable asset for a shadowy U.S. government agency. Lastly, James Wainwright appeared in Jigsaw as a determined but kindhearted plainclothes detective with the California State Police Missing Persons Bureau. That neither Search nor The Men was renewed came as no surprise to the many pundits who’d panned them.

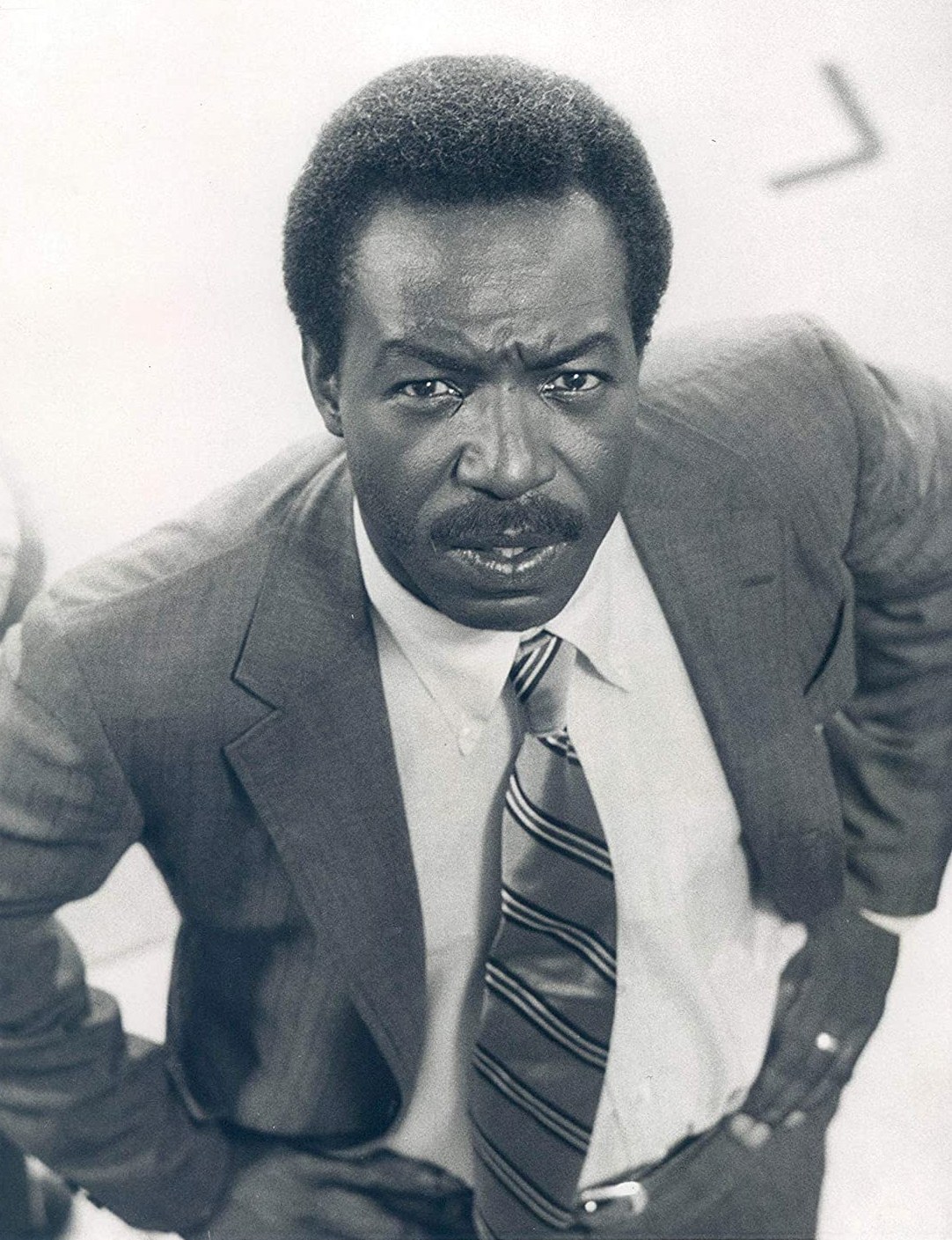

The NBC Wednesday Mystery Movie fared little better. Of its inceptive segments, Banacek was the sole survivor of its inaugural season, and went on to be joined in the fall of 1973 by three entirely different companion shows. Faraday and Company imagined longtime cinema hoofer Dan Dailey as Frank Faraday, a private investigator who’d been wrongly convicted of killing his partner and then sent away to a Caribbean prison, only to escape 28 years later, return to his L.A. stomping grounds, and try to resume business—this time with a new, less behind-the-times colleague: the grown son he never knew he had. A couple of other aging but venerable vedettes, Helen Hayes and Mildred Natwick, headlined The Snoop Sisters, the former in the role of Ernesta Snoop, a best-selling Manhattan mystery novelist, the latter hired on as Gwendolyn Snoop Nicholson, her sibling’s amanuensis and fellow amateur sleuth. Although the scripts they were given could be silly, Hayes and Natwick made a wonderfully perceptive and gutsy pair of geriatric Nancy Drews. And in the Levinson and Link-devised Tenafly, James McEachin donned the identity of Harry Tenafly, a middle-class black ex-cop, who now punches the time clock at a large L.A. private detective agency and strains to balance his professional responsibilities with the needs of his young suburban family.

But NBC’s efforts to salvage its second Mystery Movie failed; that half of the franchise was cancelled in March 1974.

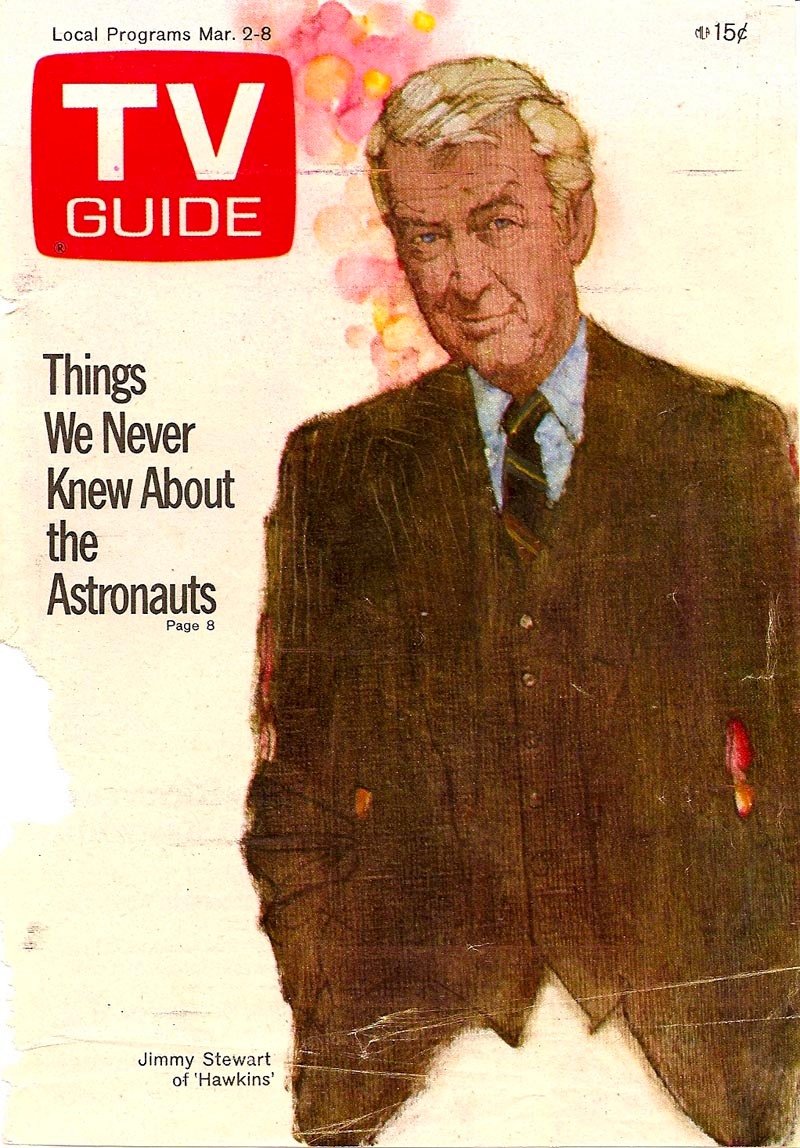

Seven months later, CBS-TV turned out its own wheel, The New CBS Tuesday Night Movies. That 90-minute timeslot proffered standalone made-for-TV films as well as a revolving pair of prestige crime serials: Hawkins, presenting Jimmy Stewart as Billy Jim Hawkins, a deceptively astute country lawyer from West Virginia, who took on high-profile, typically sordid homicide cases all over the United States, usually with fact-finding assistance from his less-than-suave cousin, R.J. Hawkins (Strother Martin); and Shaft, a significantly toned-down spin-off from Richard Roundtree’s action-filled films about John Shaft, the sexy and often violent New York City P.I. Neither lingered beyond seven regular episodes.

Even Sunday’s classic Mystery Movie couldn’t escape woes. NBC’s decision, in preparation for its 1975–1976 season, to stretch that wheel’s constituent parts from 90-minutes long to two hours left them all feeling padded. Saint James dealt McMillan & Wife a fatal blow when she left that show in 1976: Mac and Sally’s romance had been a mainspring of its appeal. And the network had a devil of a time finding a durable fourth spoke. Hec Ramsey bit the dust after two years, and a succession of replacements—Amy Prentiss (showcasing Jessica Walter as San Francisco’s first female chief of detectives), McCoy (in which Tony Curtis played a compulsive gambler who rights wrongs through flimflammery), and Lanigan’s Rabbi (based on Harry Kemelman’s novels about clerical crime-solver Rabbi David Small, with Art Carney as Small’s police chief ally)—were shorter-lived still. Ironically, it wasn’t until the Mystery Movie’s sixth and concluding season that a sustainable addition was finally found: Quincy, M.E., starring Jack Klugman as a Los Angeles medical examiner prone to horning in on police inquiries. After just four episodes, though, Quincy was converted into a hour-long weekly series (to run until the spring of 1983), while the Mystery Movie disappeared in the spring of 1977.

“I believe NBC made a fatal mistake when they expanded the Mystery Movie to two nights,” Goldberg says. “It made the series less of an event. And they tried far too many different concepts, most not nearly as well-conceived or well-written as their established mainstays (Columbo, Banacek, McMillan & Wife, and McCloud). It diluted the brand, and all the bad shows turned off viewers. The Mystery Movie lost its cachet.”

* * *

With the passing of NBC’s Mystery Movie, the decade-long heyday of TV wheel series effectively ground to a halt. Further attempts were made to milk the trend, but none of those shows could recapture the magic of their forebears.

In January 1977, ABC kicked off The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, an hour-long Sunday program based on two long-running book franchises about teenage Sherlocks; it held on for three seasons. Twelve years later, that same network brought viewers The ABC Mystery Movie, which resurrected Columbo as part of a cycle with two fresh dramas: B.L. Stryker, starring Burt Reynolds as a houseboat-living Miami shamus, and Gideon Oliver, based loosely on a succession of novels by Aaron Elkins and led by Louis Gossett Jr. as a Columbia University anthropologist-cum-detective. In its second year, the Gossett show was booted in favor of Christine Cromwell, with Jaclyn Smith (of Charlie’s Angels fame) playing a talented defense attorney, and Kojak, a revival of Telly Savalas’ 1970s CBS cop hit. Although ABC ditched this wheel after two years, Columbo telefilms continued to dribble out until 2003.

Whether out of unwarranted optimism or mere habit, NBC took one last crack at a two-hour wheel in 1993. Beneath its Friday Night Mystery banner resided a few original shows (such as MacShayne, featuring Kenny Rogers as a gambler turned head of security at a Las Vegas casino, and Ray Alexander, which brought back Gossett, this time as a San Francisco soul-food restaurateur with a taste for trouble), plus new entries in Richard Crenna’s Janek series of films (casting him as a Big Apple police detective) and movie-length installments of Hart to Hart, the 1979–1984 Robert Wagner/Stefanie Powers mystery. Those shows failed to gel, and the Friday Night Mystery vanished after a year.

It’s easy now to look back at the classic wheel series nostalgically, to forget that not all of them were created equal. Still, in an age before throngs of cable-TV channels and streaming services, when the small screen was dominated by just three big networks, those alternating dramas—their stars and components appearing occasionally enough to be considered special events—enriched the diversity of what audiences could enjoy each week. At their best, the shows felt like free theatrical pictures, complete with prominent guest performers and touches of social relevance, though for my money, never enough Greek chorus interludes.