—This piece originally appeared in NOIR CITY magazine.

In 2009, a representative of the firm of Bloom Hergot Diemer Rosenthal LaViolette Feldman Shenkman & Goodman, LLP contacted me and my three siblings about a film project. The client of this wonderfully-named law office was Shane Black, who had previously made millions from his screenplays for Lethal Weapon and Iron Man 3 and was now considering making a movie partly inspired by our recently deceased father’s 1973 novel Blue Murder. Could Robert Terrall finally be getting a shot at the big time after a long career toiling as a little-known genre writer?

Fast-forward five years. A new message from Mr. Black’s law firm arrived in our inboxes, informing us that “The project had become inactive, but now our client would like to begin pursuing it again.” We signed over the rights and each received checks for $2.50, soon forgetting about the project. Then in 2016, when The Nice Guys was made, with Shane Black’s writing (co-scripted by Anthony Bagarozzi) and directing, we each received $2,500, a somewhat more memorable occasion than the first payment.

It was a bit bittersweet to see “ACKNOWLEDGMENT TO ‘BLUE MURDER’ AND THE WORKS OF BRETT HALLIDAY, SPECIAL THANKS TO ROBERT TERRALL” roll by onscreen (the $2,500, of course, had been entirely sweet). I have no doubt Dad would have loved to see his name on the silver screen. He was a moviegoer from an early age and was always ready to write for Hollywood, but that never happened. He wrote several movie tie-ins (including one for Moses and the Ten Commandments, which made it possible for me to answer the question “What has your father written?” with “The Ten Commandments”), but none of his fifty or so original novels were ever made into films. He got his hopes up when a book of his was optioned by some mover and shaker—but those hopes were dashed when Dad opened the paper and saw the obituary of that same moneyman.

My father was a professional writer his entire working life. He held one salaried job after graduating from Harvard (where he edited The Harvard Lampoon): writing for Time Magazine. Time‘s editor Henry Luce hired Dad to write humorous pieces but apparently the work was not to Luce’s liking, and Dad was fired. There’s no one alive who can say whether or not the notoriously right-wing Luce ever found out that Dad stayed up late editing the clandestine left-wing newsletter which was distributed among radical Time employees.

Dad’s first novel, They Deal in Death, about nazi diamond smuggling, came out in 1943. His second, A Killer is Loose Among Us (1948), is the most “noir” of any of his books, a germ warfare story that reads like a fever dream from the Jim Thompson end of the bookshelf. The Steps of the Quarry (1951), based on my father’s WW2 experiences helping to liberate a concentration camp, was his first attempt at “serious” fiction, which is what he aspired to write. But that ambition was thwarted when The Steps of the Quarry was mostly ignored by critics and the public, so he went back to writing mysteries to support his family (my eldest sister and mother).

Dad wrote some short stories for The Saturday Evening Post and other publications, but by the early 1950s that market was drying up. The paperback original, however, was beginning to take off, and my father hit his stride writing crime fiction for paperback publishers. In the ’50s he wrote “stand alone” crime novels and a detective series about a cigar-smoking private investigator named Ben Gates (under the pseudonym Robert Kyle). In the early ’60s he wrote another series featuring a more comedic gumshoe named Harry Horne (written under the pen name John Gonzales).

My father was fondest of the Harry Horne books, which gave him a chance to inject humor into more interesting stories, but neither line was lucrative enough to keep publishing. I had already been added to the Terrall household expenses when the offer to take over the Mike Shayne series came along. Dad was hired to take over writing the series from Davis Dresser, Shayne’s creator, in the early 1960s. Dresser had developed a severe writer’s block, which left my father with steady work cranking out two books a year. (There were a few other writers who also wrote Shayne books in the late ’50s and early ’60s.)

Michael Shayne was a tough, red-headed Irishman who operated out of Miami. This character was a licensed private investigator who would bend the rules if he had to and could take care of himself when push came to shove and punch. He came into my dad’s working life in time for the cultural upheavals of the 1960s and the burnout of the ’70s, which make many of the Terrall-authored Shayne novels interesting, if sometimes dated, period pieces. The dialogue in Blue Murder doesn’t always have the ring of historical authenticity, as when one character asks another, “You don’t happen to be a grasshead, do you?” Elsewhere in the book an ex-con refers to being busted for possession of a “marijuana cigarette,” not exactly hardened hippie vernacular. But otherwise the writing holds up today. The reference book 1001 Midnights: The Aficionado’s Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction has this to say about my father’s contribution to the Shayne franchise: “Terrall is a fine writer, a more subtle and accomplished stylist than Dresser, and his Shayne novels deserve attention. He injected new life into a rather played-out series, and came up with fresh story material.”

Classic cover paintings by such dimestore favorites as Robert McGinnis graced the early ’60s Shaynes, but by the middle of the decade photographs of at most scantily-clad vixens helped sell the books. The photo on the cover of Blue Murder is a personal favorite of mine: Shayne, portrayed by a rugged-looking guy with his shirt partly unbuttoned, is staring at a strip of 35 mm film; the model has just enough gray in his modest sideburns to suggest years of experience being a hardass. Reels of film are stacked in front of him, and a striking brunette displaying unclothed curves is draped over his shoulder. The blurb on the back cover is to die for: “MIKE SHAYNE, THE PRIVATE EYE WHO PLAYS IT AS IT LAYS, TAKES A STARRING ROLE IN AN X-RATED CASE OF WARM SEX AND COLD BLOODED MURDER.” And: “Before Mike got down to bare facts, he was up to his libido in blackmail, violence, skin flicks and bad, bad trouble.” Though tame by today’s raunchier standards, there tends to be enough sex in the ’70s Shaynes to make me cringe in familial awkwardness, as few of the attractive females the P.I. encounters are able to resist his hunky appeal.

My father spent about a quarter of his time on the Shayne books working out the plots. The narratives could get pretty complicated, so much so that he had the word “simplify” taped above his writing desk. Typically of his sense of humor, the letters had been elaborately drawn by an amateur calligrapher.

Blue Murder‘s machinations were not influenced by the word above my father’s desk. Shayne is hired by a crusading anti-porn congressman to find his wayward wife, who had gone AWOL to spend time doing God knows what with a pack of sleazy pornographers. The deeper Mike delves into the congressman’s past and the wife’s present the more complicated things become. I don’t want to spoil the story for pulp-hounds who might go back and read it, so suffice it to say that things get progressively messier, especially when an underworld character named Pussy Rizzo (!) enters the picture. The mystery is resolved after Shayne rounds up all the players for a sit down where he delivers a monologue which untangles the story, in the style of Nick Charles’s dinner party exposition at the end of The Thin Man.

Having been less than enthusiastic about Shane Black’s script for the 1991 Bruce Willis vehicle The Last Boy Scout, which I watched at a grindhouse matinee years ago, I went to see The Nice Guys with high hopes but low expectations. Unlike many reviewers, I was more than pleasantly surprised. My sister Mary also liked it. My sister Susan thought it was too violent and found the male leads, Ryan Gosling and Russell Crowe, to be unfunny. Like my brother Jim and my nephews Greg and Noah, I disagreed. Noah wrote me, “A little over the top at times but good dialogue, characters, and plot.”

Well, the plot was a little slipshod, but that shortcoming was more than compensated for by the great late ’70s costuming and set design, not to mention the comedic chemistry between Gosling and Crowe. High body count notwithstanding, the most excruciating violence occurs early in the movie, when one of the stranger meet cute scenes I’ve ever watched concludes with an arm being broken. From there on it’s mostly an affectionate parody of traditional private eye tropes, with Gosling as a sodden boozehound detective whose hapless ineptitude is offset by the guiding hand of his teenage daughter Holly (the scene-stealing Angourie Rice), his designated driver and the brains behind his operation. Crowe’s thuggish tough guy, quick to resort to brass knuckles, provides a deadpan foil to Gosling’s unhinged shenanigans, which peak with what must be the funniest armed man in bathroom stall scene in film history.

The Nice Guys made a profit, but unfortunately didn’t stay in theaters long enough to justify a sequel. For reasons beyond my comprehension, audiences were more attracted to such competition as The Angry Birds Movie and Captain America: Civil War. Viewing The Nice Guys a second time, I was happy to find myself still entertained by it. The movie has an out of kilter oddball appeal that gives it staying power. I’ll even go out on a limb and say that it wouldn’t be entirely out of place on a double feature with The Big Lebowski.

So what did The Nice Guys lift from Blue Murder? On first blush, not a hell of a lot. The film is a slapstick buddy movie with a mile-wide irreverent streak. Blue Murder, on the other hand, mostly sticks to a traditional late 20th century private eye formula: Shayne is a sharp operator who keeps things as cool as possible, and the book’s action is far from the surreal, blood-soaked giddiness of the Nice Guys‘s second half.

Perhaps earlier iterations of Black and Bagarozzi’s script included more specific plot details taken from Blue Murder, but the finished film only recalls the woman who goes missing in the porno world angle, along with a missing film reel that the principals are searching for. There is also a malevolent politician in both stories, but the parallels do not exactly recall Led Zeppelin lifting Willie Dixon’s lyrics.

As far as I’m concerned, Shane Black is a mensch for contacting my family for formal permission to go forward with The Nice Guys. I doubt if the similarities to Blue Murder, such as they are, would have been noticed by the most hardcore fan of my father’s work.

To add a further amusing wrinkle to this encounter with Hollywood, Charles Ardai wrote a novelization of The Nice Guys. Ardai is the brains and editor behind the stellar Hard Case Crime imprint, which brings long out of print crime novels back into circulation and also publishes some new titles, including this movie tie-in. Like Ardai’s other three novels for Hard Case Crime, the novelization of The Nice Guys is entertaining and very well-written. It sticks closely to the action of the movie and manages to capture the humor of its source material without lapsing into cuteness. Ardai closely follows the screenplay, but also adds some asides and small bits of great dialogue here and there which enhance the story’s comedic punch.

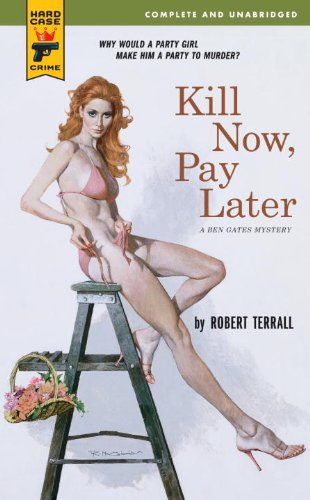

Ardai is also the man my sister Susan wrote about reprinting one of our dad’s novels as part of the modern-day paperback line. He was already aware of Dad’s work, and loved A Killer is Loose Among Us. As Ardai recounted in an online interview, “When she [Susan] contacted me I sat down and read pretty much everything he’d written, and of the lot I enjoyed Kill Now, Pay Later the most.” Novelist and pulp historian Ed Gorman echoed Ardai’s enthusiasm, calling that Ben Gates vehicle “a fine read” which “demonstrates how admirable and readable a really fine craftsman can be.”

Kill Now, Pay Later was brought back into print, with a Robert McGinnis cover, two years before Dad died. Having one of his books reprinted under his own name rather than the pseudonym Robert Kyle gave my old man a great deal of satisfaction.