While sitting in the balcony of a movie theater waiting for Jordan Peele’s much-anticipated horror film Us, I began thinking about my personal relationship with the horror genre. “When I was pregnant with you I used to watch scary movies all the time,” my mom confessed years before as we left the Roosevelt Theatre in Harlem one afternoon after a screening of Night of the Living Dead. Although I was only seven and much too young to have seen that first zombie apocalypse, which gave me nightmares for a week, but afterwards I became a horror junkie. As much as I might’ve nervously jumped while watching The Blob, The Fly or Dracula, it was those stories that appealed to me.

During that same era I was led further astray down the pop culture rabbit hole when I transformed into a rabid comic book fan. Enthralled by the vivid art as well as the incredible stories of costumed freaks fighting for justice, every week I stood at the newsstand on a 159th Street and Broadway searching for the latest four-color delights. In the beginning I bought mostly what my friends read, traded and talked about which included The Avengers, Superman, The Hulk, Batman, Daredevil and other supermen who, every month, were out to save the world.

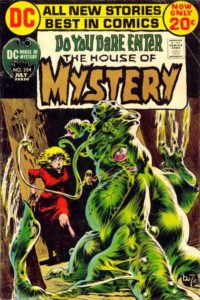

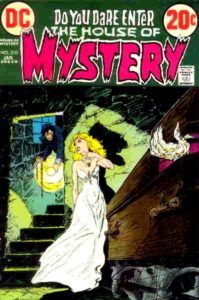

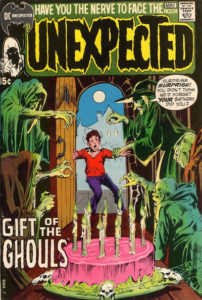

After awhile I got tired of most superheroes and had little interest in memorizing the minutia of the Marvel/DC universes. I didn’t want commit to long storylines that sometimes stretched for years and began looking for alternatives to the men in tights adventures. One summer day not long after I turned ten, I scanned the newsstand racks and noticed towards the bottom a clutter of comics that were, as I was to soon learn, the horror selections. With titles that consisted of House of Mystery, House of Secrets, Unexpected and Ghosts, all published by DC Comics, they were anthology styled books that featured multiple short stories that ran between 6-8 pages with most issues running three separate tales per book.

Already addicted to the television anthology format from watching reruns of The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits and One Step Beyond on local channels, these comics was the perfect fit. Many of the horror artists had creepy and/or strange drawing styles that weren’t conducive to drawing Superman or Captain America, but were perfect for the Poe/Lovecraft inspired gothic stories. The covers were always sinister images of ghastly ghouls, cemetery creatures, scary skeletons and voodoo villains, with artists Neal Adams, Bernie Wrightson and Michael Wm. Kaluta contributing some of the best.

The interior pages were drawn by various people, including veteran Alex Toth and newcomer Mike Golden, but the artist whose work I looked for constantly was Alex Nino, who drew in a crazy cosmic style that was purely original. Nino could portray many moods and emotions with his impressionist lines that were stunning. His layouts broke with tradition, and, like Wrightson and Kaluta, he was perfect at both horror and science fiction. Hailing from the Philippines during a time when many of his countrymen, including Alfredo Alcala, Ernie Chan and Nestor Redondo, were also coming to the States to illustrate comics, these artists brought a fresh perspective to the books.

Meanwhile, the regular script writers were Len Wein, Steve Skeates, Jack Oleck and Nick Cuti, who was actually a writer/editor at Warren Publishing, who published the black and white comics Creepy, Eerie and Vampirella. The stories were moody and atmospheric that was sometimes psychological and often used O. Henry type twist endings. These were the men that served as my first literary heroes, whose work became a guide when I decided to start composing short stories.

Many of the creatives working on these books were inspired by the EC Comics line from the 1950s that included Tales from the Crypt, The Haunt of Fear and The Vault of Horror, where legendary artists Frank Frazetta, Al Williamson, Bernard Krigstein, Graham Ingels, Jack Davis, Harvey Kurtzman and Joe Orlando, who, beginning in 1972, was the lead editor on the DC horror books I bought. The EC writers, led by Al Feldstein, included Robert Bernstein, Otto Binder, Daniel Keyes, Jack Oleck and Carl Wessler. Decades later, the EC team was cited by Stephen King, George Romero and Steven Spielberg as their own inspirations.

In truth, though I was young, I was already writing on the Olivetti typewriter I got for Christmas the year before and somehow convinced myself that writing scripts was next logical step. Nick Cuti was also the creative force behind the pamphlet sized instruction booklet The Comic Book Guide for the Artist-Writer-Letterer. Produced by Charlton Comics, the booklet broke down the format and mechanics of the work in a language that was straight forward. After reading the book a zillion times (it’s only 35-pages long), I wrote Cuti a letter at Warren gushing over his own writing and telling him that I too wanted to be a comic book scribe.

Two weeks later, I was surprised when he wrote back offering encouragement. “Even if you do want to become a comic book writer, you must read more than comics,” he advised. Although I was already a fan of the strange tales of Roald Dahl, the aesthetic I developed from the horror comics sent me straight into the frail arms of Franz Kafka and Edgar Allan Poe.

***

The summer of ‘77 had been a long, hot one that included the release of Star Wars, the birth of Heavy Metal magazine and the death of Elvis, which happened a few weeks before the beginning of the school year. I was also starting high school and was readying myself for the challenge of Rice, the all-boys Catholic school I would be attending. Classes began the first week in September, and from jump my favorite class was Brother Pearson’s English class where we were reading The Tale of Two Cities. Brother Pearson also was the school paper advisor, and I joined the staff as soon as I could.

Writing more, I started flirting again with the idea of writing comic book scripts. Returning home from school, I dared myself to call DC Comics from the rotary phone in the kitchen and convince them of my brilliance. After getting the number from 411, I called and, much to my surprise, I was turned over to a young editor named Paul Levitz. Not really knowing what to say, I finally blurted, “I would like to write comics.” Much to my surprise, Levitz gave me an appointment to visit the office, and to bring my work, the following month. Although Joe Orlando was the main editor on the horror books, Levitz was the editorial coordinator.

During the 1970s, with the exception of a few artists (Billy Graham, Keith Pollard, Ron Wilson and Trevor Von Eeden), there weren’t many African-American creators working in commercial comics, something I noticed when I attended my first comic convention that same year. However, while I didn’t see any scripters that “looked like me,” that wasn’t going to keep me from trying. Truthfully, I wasn’t trying to be the Rosa Parks of horror comic book writers, I just wanted to be down.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the horror books were often used as the jump-off, where many young creators got their start before moving on to bigger books. I spent the next week knocking out plotlines, mostly ripped-off from too many viewings of Chiller Theater and Creature Features, to present at our meeting. Following Cuti’s guide, I also produced a four-page script to present to Levitz. While comics are often thought of as a subgenre to real literature, I learned a lot about pacing, dialogue and foreshadowing as well as sharpening my visual sense.

Truthfully, I wasn’t trying to be the Rosa Parks of horror comic book writers, I just wanted to be down.The mid-October day of our meeting, I was nervous as hell and left for school early to guarantee that I wouldn’t get a late detention. At Rice High, one could get detention for almost anything, so I made sure I was on my best behavior. I had gotten my mother to retype the plot pages and script, which she had put in a yellow manila envelope, and between class periods I checked my locker to make sure the packet hadn’t evaporated. Time moved slowly. Sometimes it felt as though it was moving backwards. When 3:00 o’clock finally struck, I rushed from the school building to the downtown subway station on 125th and Lenox.

A half-hour later, I was nervously walking through the golden doors of 75 Rockefeller Plaza. Arriving at DC Comics still wearing my school uniform (dress pants, shirt, tie and jacket) that in my mind doubled as a business suit, I was shown the reception area where I was asked to wait. I can’t remember much about the décor, but I did get into a long chat with artist Romeo Tanghal, who was waiting for the art director. He had recently arrived from the Philippines and had just started drawing for the horror books. “That’s the stuff I want to write,” I said excited. I remember him smiling warmly as he balanced a black portfolio case between his legs. “That would be nice,” he answered, his English not the best in those early years. “Maybe I’ll draw one of your scripts.”

Finally, Paul Levitz came out to greet me. A skinny young man in glasses, mustache and a suit, he escorted me into his small office. With his jet black hair, he was only seven years older than me, but when you’re a kid that feels like a million. After listening to my fan boy chatter, with me nervously explaining how I was born to write horror comics, I handed him the typed plots that he quickly scanned. “This is interesting,” he said. Seconds later his boss Joe Orlando barged in and tossed some envelopes on Levitz’s desk. Paul introduced us, and since I had read a lot about the early days of EC and glanced at some of the reprints, I knew Joe’s work well. Joe looked at me, grunted something, and walked away.

Minutes later, Paul and I were interrupted by a jovial by Dick Giordano, who seemed like the coolest man in the world. “Nice to meet yaw,” he said in his heavy New York accent. Unlike the other old-school comic guys, Giordano looked like those sharp advertising guys in Doris Day movies. After he left, Levitz reached into a file on his desk and pulled-out a script by writer Bob Toomey and instructed me to study it. “Use it as a guide, and call me back when you have a few scripts.” I held on the script as though it was a golden ticket to Wonka Land.

“All right,” I mumbled, still hardly believing I had made it through the door in the first place. We shook hands and I was gone. Walking out of the building, I wanted to twirl around like Mary Tyler Moore and throw my book-bag into the air. In my mind, I was already half way there and surely within a few months I would be a comic book writing fool.

Levitz might’ve realized that every novice needs someone to take their work seriously and prove to them that their dream isn’t impossible to achieve.Although I’d go back to visit Levitz twice, bearing new horror scripts each time, at fourteen, I was far from ready. Still, though I would never sell any scripts to DC Comics, the lessons learned about professionalism, from having the courage to connect with the editor to manuscript presentation to rewriting after an editorial meeting, were invaluable towards establishing my career as a music journalist, book critic and short story writer. As a young writer/editor himself, Levitz might’ve realized that every novice needs someone to take their work seriously and prove to them that their dream isn’t impossible to achieve.

In 2007 when my crime writing/comic book scripting buddy Gary Phillips invited me to contribute to the collection The Darker Mask: Heroes from the Shadows, which he co-edited with Christopher Chambers, it was explained to me that the pieces would be the textual equivalent of comic book superhero stories. By that time, thanks to seminal works by Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz and Howard Chaykin, whose offbeat neo-space opera hero American Flagg was a favorite in the 1980s, I had gotten over my aversion to costumed champions. Still, as with most of my fictions, there was a considerable spooky electric darkness circulating through my story The Whores of Onyx City, a dystopian tale of human horror that was inspired by those scary comics that I once dreamed of contributing to so many years ago.

Although Levitz and I hadn’t stayed in touch, I knew of his rise through the corporate ranks as he would go on to become the publisher and president of DC Comics. After finishing my story, I read it back a few times and decided that I wanted to close the piece with a dedication: For Paul Levitz, for encouraging me back in the day.

__________________________________

More on CrimeReads

__________________________________

Read an essay by Paul Levitz about the ghosts of New York City.

Read an essay by Michael Gonzales on a lost Chester Himes classic.