Women love true crime. While certainly not a universal truth, it’s a generalization that feels apt enough that even SNL has noticed. On February 27, the song spoof “Murder Show,” aired to general acclaim — if the women I follow on Twitter are any indication. As the skit begins, Nick Jonas leaves his girlfriend alone for an evening of unwinding and self care. Bubble baths and sheet masks come to mind. But as soon as he shuts the door behind him, she curls up on the couch, opens Netflix, and breaks into song about the specific delight of watching murder shows.

It’s the kind of parody that works because it feels a little perverse. This is a guilty pleasure, emphasis on the “guilty.” The women of SNL sing about the grisly murders they watch with alarming passivity, even unconcern. They relish in details dismembered limbs and satanic killers while they eat pizza, text about babies, even do their taxes. The skit makes light of a tension that, if you think about it for a moment too long, becomes uncomfortable. Women love true crime, to the point where the most extreme violence can become commonplace to them. Even when women are often the victims of that violence.

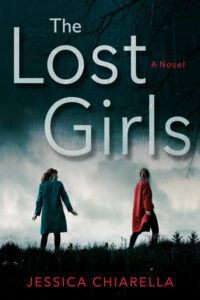

It’s a tension I struggled with while writing my novel The Lost Girls. The story centers on Marti, an amateur podcaster on a quest to find her sister Maggie, who went missing when they were children. On its face, Marti’s motivation is simple: to draw attention to her sister’s case, in hopes of drumming up potential new leads. But the more I put myself into Marti’s head, the more I realized that her true aim might also answer the question of why so many women adore true crime: because it creates a narrative.

It’s not that Marti believes she’ll find her sister, though that doesn’t stop her from compulsively trying. But what she wants most is to tell Maggie’s story, as well as the story of the broken family Maggie left behind. Marti wants to make her sister real again in a way that magazine coverage, or local news, or their mother’s efforts to cast Maggie as a perfect victim simply can’t. And in realizing that motivation for my character, I began to recognize it more and more in the true crime I was bingeing. Creating a story where before there were only basic facts allows for complication and deep empathy that often doesn’t exist in general news coverage. In that way, these murder shows can be moving, and—dare I say—oddly comforting.

It’s not a surprise that this aspect of true crime connects to people on a deeper emotional level than simply reporting a case’s facts. But beyond that, true crime can even be a counterbalance to the anxiety of moving through an often-violent world. For many women, particularly those who grew up in the pre-internet age, the dangers of American society can feel both arbitrary and ubiquitous. When I was a child, the nightly news reported an endless string of kidnappings and rapes and murders while providing little or no context to the crimes, much less the victims. Stranger danger created the specter of the man lurking in the bushes, ready to assault or kidnap indiscriminately. Despite how flimsy this reality was (such as the fact that women are statistically much more likely to be assaulted or killed by someone they know), it’s not surprising that a generation of women grew up at once hyper aware of—and also somewhat inured to—the sense of ever-present danger around them.

In this way, true crime acts as a corrective. Its very existence demonstrates that there is something to be gained by delving into detail, by slowing down and unpacking the story of a crime. It makes people of its victims by telling the stories of their lives and the circumstances that brought them to their end, instead of just examining the aftermaths of their deaths. It lends context to its violence. By trying to find narrative in a series of events, it satisfies the human need to find order amid seemingly indiscriminate chaos.

But true crime sometimes does even more than that. At its best, true crime lends a specific agency to its storytellers, be they journalists or documentarians or part-time internet sleuths. From Serial to Making a Murderer to the movie Zodiac, true crime is full of examples of everyday people delving into mysteries that the professionals were unable to solve, or perhaps have gotten wrong. The most gratifying examples are when true crime has an impact on the legal status of a case, such as The Jinx, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, and the In the Dark podcast. It’s part of what keeps fans coming back—for each such victory, the promise of more victories to come grows sweeter.

But more often, the satisfaction is only personal: the discovery of a truth that the legal system has failed to provide. It’s the triumph of Jake Gyllenhaal at the end of Zodiac, standing in a hardware store looking into the eyes of the man he believes to be the infamous serial killer, while Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street” swells in the background. In the end, he doesn’t need a court to find the man guilty. All he needs is for the killer to understand he’s been found. It’s also the reason that an argument about Serial got so heated one night that one of my friends left a bottle of whiskey on our kitchen counter the next day. A peace offering, with a sticky note reading “Adnan did it” affixed to the label. What we believe has always felt more significant than what we can prove.

At its core, true crime invites us to believe that our discernment, our empathy, and our opinions matter. It asks us to consider the story presented to us and decide for ourselves what the truth of the case is. And it empowers us with the understanding that sometimes a dogged amateur looking for a narrative thread can uncover something the professionals missed. Context becomes not only important, but essential to an investigation. And unlike the thirty-second summaries on the nightly news, each time we watch or read or listen to another story, true crime allows us to identify with the investigator instead of with the victim.

***