“Do you hear that?”

My treasure-hunting partner, Beep, kept his eyes glued to the map. “Hear what?” he asked me without looking up.

“It sounded like thunder,” I said, glancing up at the sky, which minutes before had been clear and blue and pristine. Now it was blackening, suddenly ominous.

We were standing on the side of State Road 68 a few miles north of Pilar, New Mexico, several hundred feet up the highway from the Rio Grande Gorge Visitor Center. In front of us stood an impenetrable mass of rock and brush, right where the map said the trail leading to Agua Caliente Falls was supposed to be.

Except it wasn’t there. It didn’t exist.

A rumble echoed through the canyon, unmistakable this time. Before Beep or I could say another word, the skies opened up and the raindrops began to fall—not a polite, drizzly rain, either. These were big, heavy drops, a cascade of water coming out of the sky with no warning and shocking suddenness.

“Run for the car!” I shouted, and we tore off toward the parking lot, a quarter mile up the road. Eighteen-wheelers rumbled by as we scampered along the shoulder of the highway back to our rented Ford Explorer. Yanking open the doors, we tumbled inside, out of breath, wet, and already defeated. We hadn’t even gotten to our search area yet.

“How did we not think to check the weather?” I asked, mostly rhetorically.

“It’s the desert. I thought the weather was always the same here,” Beep said, looking perplexed. A pasty Canadian, he was shivering in the passenger seat in a gray fantasy sports T-shirt and black gym shorts, fully unprepared for the deluge. At least he was wearing a boonie hat he’d purchased because it seemed like good hunting gear, its floppy brim partially hiding his people-pleaser eyes. Just as well. I figured he’d be looking at me with disappointment for my embarrassing lack of preparation.

Quite the auspicious start to our careers as treasure hunters.

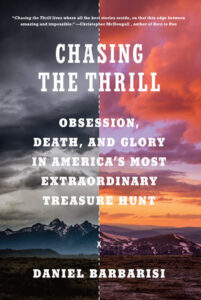

Treasure hunters. It still sounded crazy. A few months before, Beep had discovered the tale of Forrest Fenn, a wealthy New Mexico art dealer who claimed to have hidden a treasure chest worth millions somewhere in the Rocky Mountains north of Santa Fe. In 2010, Fenn published a book and a poem that promised to lead searchers to the treasure—if they could figure out the poem’s nine clues. Beep had become completely obsessed with the chase, and I’d followed him down the rabbit hole.

We’d flown into Albuquerque the day before, and made our way up to Santa Fe later that night. Then early the following morning, Beep and I had stowed our newly purchased treasure-hunting gear and jumped into the car for the two-hour drive north through the wilds of New Mexico, the kind of place that isn’t really barren but is still sparse enough that you mostly lose cell service. Once outside of 85,000-person Santa Fe, the starkness of the landscape is stunning: flat and broad for miles and miles in every direction, until that land runs into mountains far in the distance on each side. We’d theorized that Fenn’s treasure must be somewhere among them—that chest and its cache of gold, diamonds, emeralds.

Driving toward those peaks, the only markers of civilization we saw were the periodic small towns, just hamlets really—a bar, a general store, maybe a school. In between them was nothing—nothing, except crosses at regular intervals along the highway, marking spots where unfortunate drivers had crashed. There were more of them than I’d ever expected, more than I’d seen along any other stretch of highway anywhere. They were our constant companions as we drove up, pacing the distance between the only true landmarks on this journey: Native American tribal casinos. They rose out of the plains like the palaces of ancient kings, massive and elaborate and blinking with lights and signs and promises of riches. There was so little along this route, and yet one of these strange oases appeared every fifteen miles or so, and the parking lots were all packed. Who were all these people? Where did they come from? They’re a bit like us, I figured, hoping to strike it rich—just in the form of plastic chips, not gold coins. And probably just as unlikely to realize their dream.

As we’d made our way to the search spot, I’d found myself growing more confident in our “solve”—our solution to Fenn’s poem, our step-by-step route to the treasure. It had actually felt as if the treasure was within reach. The spot we were seeking was barely marked—it didn’t even show up on Google Maps, the world’s current digital arbiter of what is legitimate and what is not. We’d found the location on a United States Geological Survey map, listing Agua Caliente Canyon and, a few miles’ hike away, Agua Caliente Falls. We’d zeroed in on the sites for two reasons. First, Agua Caliente means “hot water” in English. In the first line of Fenn’s poem, the all-important verse that is supposed to lead searchers to the treasure, he advises seekers, “Begin it where warm waters halt/And take it in the canyon down.”

Many people have taken that instruction literally—seeking out a spot where a river changes in temperature, or where a hot spring hits another body of water. But what if Fenn was just playing with words? What if, instead, he wanted us to start where “warm waters halt” in a different way—to begin where Agua Caliente Canyon ends, and then follow the canyon itself off into the wilderness? From there, we’d make our way to Agua Caliente Falls, which could be the site of “heavy loads and water high,” one of the other clues in the poem.

This seemed like a pretty good idea when Beep and I were hashing it out back east, I from my home in Boston and he from his outside Toronto. But now that we were on the ground, hiding in our car, our internet searching seemed remarkably naïve.

“It’s a lot easier to do it from your computer,” Beep said, giving voice to my thoughts.

As we sat pondering this painfully obvious truth, something started peppering the car. Not rain anymore, but actual physical objects.

Hail.

Hailstones the size of pebbles pelted us by the thousands as we cowered in our rental SUV, still fresh with its new-car smell. I cringed as the little ice balls pinged off the car’s exterior with a machine-gun rat-a-tat, desperately hoping they weren’t leaving dents. I definitely hadn’t paid for the rental insurance.

“Wow” was all Beep could muster. I couldn’t even manage that.

“Should we just head back?” I asked, realizing how silly I’d been to think we could find a hidden treasure. We couldn’t even get out of the car!

But Beep wasn’t ready to go just yet. He had been lukewarm about this spot anyway, noting that Agua Caliente Falls was listed on the map at a higher elevation than the start of Agua Caliente Canyon—so we’d be taking the canyon up, not going “in the canyon down” as Fenn directs. He’d also politely noted the distinction that in English, Agua Caliente technically means “hot water,” not “warm water”—which I knew, but, hey, I hadn’t heard him offering any bright ideas.

“Let’s drive around a little,” Beep suggested now. “Let’s drive along the river.”

Might as well.

The hail was weakening, replaced by a hard rain, which was roiling the Rio Grande. The river looked mean and dangerous now, the water high and running fast as I took our truck down the road that ran alongside it.

Suddenly, Beep pointed at a sign, one marking a side road leading to a small bridge across the river.

“That sign says Agua Caliente Road—is that on the map?” he asked. “Maybe that means something. Maybe that means we’re on the right track.”

I could hear that glimmer of excitement start to creep into my compatriot’s voice, so just to humor him, I drove a little farther down that way, bringing us to the entrance to Rio Grande Gorge. Most of the good maps were back at the Visitor Center, but there was at least a sign here marking the actual entrance and offering some basic geographical info. Beep got out to examine it. The gateway to the Rio Grande Gorge sat at the end of what seemed to be a tiny town, stuck out here on the edge of nowhere. From the car, I could see a few ramshackle houses dotting the sides of the river. One seemed to be guarded by a pair of ferocious-looking dogs. I thought about getting out to help Beep but decided to stay in the car. Hey, I’m a cat person.

Beep returned sooner than I expected, tearing open the car door, panting with excitement. Apparently, there was a Rio Bravo Campground up ahead, which Beep thought might be connected to one of the lines in the poem, “If you are brave and in the wood.” His logic was that the word brave is bravo in Spanish, which keeps with the Agua Caliente/warm waters translation theme, and the campground was in a slightly woodsy area. And on top of that, there was an advisory that this was a brown trout fishing grounds, which could link to another line in the poem that suggests we “Put in below the home of Brown.” Maybe that meant finding or using a boat put-in? A place where you’d go fishing for brown trout? Fenn, after all, was a big trout fisherman.

“I didn’t expect to find anything there,” he said. “But then I saw the Rio Bravo Campground sign, and the map talking about brown trout, so now I think we might really have something.”

I was still feeling a bit deflated, but Beep’s enthusiasm was contagious. It had always been that way with us; I could be the dour, realistic half of our partnership, and he would be the effervescent, never-cowed, slightly insane side of our coin. It worked well. At least it certainly had in the past. Beep had served as my mentor when, in 2015, I quit my job as a reporter at The Wall Street Journal to tell the story of the burgeoning phenomenon of daily fantasy sports from the inside; Beep had guided me on the way to claiming the title of Fantasy Hockey World Champion. Beep—real name Jay Raynor, but widely known by his fantasy sports username, BeepimaJeep, or usually Beep for short—was a legend in that arena, known as one of the top players, certainly, but also as one of the most eccentric. His penchant for wearing a quasi-uniform of a lopsided baseball cap and a T-shirt with an animal of some sort on the front distinguished him on the scene, and his odd talents made him stand out further. He was a former Canadian National board game champion, a self-taught foosball virtuoso, and a wealthy fantasy sports winner despite knowing virtually nothing about sports. I’d once described him as a “Renaissance man of the frivolous,” and I think that still held true.

Over time, I’d learned to trust Beep’s hunches; even my wife, Amalie, a reporter for NHL.com, had come to believe in them. She was back home, eight months pregnant with our first child, a boy. We had decided to name him Elliott, and I couldn’t wait to meet him. Even so, when I’d explained that I needed to fly out to the Rocky Mountains to chase a treasure because Beep thought he had an idea about where it might be, as insane as that seemed, she understood. I married well.

Now Beep was getting enthusiastic again, believing that we were back on the right track. What if, miracle of miracles, we’d started in the right place after all—but had been trying to go the wrong way from there? Maybe Fenn really had wanted us to begin where Agua Caliente Canyon ends, but instead of heading east toward Agua Caliente Falls, he meant we should go west, down into the Rio Grande Gorge. Maybe the gorge itself was his “canyon down.” And then maybe we should seek out those brown trout fisheries.

A burst of excitement flared up inside me. The rain was even letting up at last, so we raced ahead toward the Rio Bravo Campground. As we sped along the river, deeper into the canyon, Beep narrated the lines of the poem in Forrest Fenn’s lilting Texan drawl. Like any semiserious Fenn hunters, we’d each read the poem so many times, we could recite it from memory. But every time, every reading, seemed to offer something new, spark a different thought. So I didn’t really mind hearing it again, Beep’s voice the only sound as we drove along.

As I have gone alone in there

And with my treasures bold,

I can keep my secret where,

And hint of riches new and old.

Begin it where warm waters halt

And take it in the canyon down,

Not far, but too far to walk.

Put in below the home of Brown.

From there it’s no place for the meek,

The end is ever drawing nigh;

There’ll be no paddle up your creek,

Just heavy loads and water high.

If you’ve been wise and found the blaze,

Look quickly down, your quest to cease,

But tarry scant with marvel gaze,

Just take the chest and go in peace.

So why is it that I must go

And leave my trove for all to seek?

The answers I already know,

I’ve done it tired, and now I’m weak.

So hear me all and listen good,

Your effort will be worth the cold.

If you are brave and in the wood

I give you title to the gold.

With the words of the poem ringing in our minds, Beep was now seeing connections everywhere—when he spotted a sign for falling rocks, he started bouncing in his seat.

“That could be the ‘heavy loads,’” he said. Not long after, we passed a metal water pipe, about eight feet above the ground, spewing liquid out onto the side of the road. Beep started to suggest that could be the very next clue, but I cut him off.

“If that’s his ‘water high,’” I said, “this treasure hunt sucks.”

Beep seemed to accept that and returned to silence as we sped along the winding road snaking along the basin of the gorge, paralleling the Rio Grande. But “water high” was still throwing us off—the river’s waters were certainly high, but it couldn’t be quite that simple, and besides, water height changes daily. Then up ahead, we saw a structure along the bank; it looked like a measuring station of some sort.

“That’s worth checking out,” I told Beep as I pulled off the road. We wandered around, eventually finding a placard telling us that this was a gaging station, one used by the United States Geological Survey to measure water height. On the back of the station itself, we found a measuring stick, charting the level of the Rio Grande.

“They actually measure water levels here,” Beep said, his hand on his chin. “This could be the kind of thing Forrest would think about. Now we just need a blaze.”

Ah. The blaze. It is the phrase about the blaze in the poem that causes perhaps the most consternation to Fenn searchers. Right after the part about “heavy loads and water high,” Fenn drops his clue about the blaze, that one should find it, and then “Look quickly down, your quest to cease.”

So if you’ve got the blaze, you’ve got the treasure. The problem? No one, anywhere, can agree on what the heck a blaze is. Some people think it’s a place name that references flame. Some think it’s a sunset, or a special tree, or a man-made marker of some sort. It could be a rock or a natural formation that looks like an F, or something else that alludes to Fenn and the treasure. A few think it’s an actual fire. That’s the thing about the blaze—it really could be anything.

I tended to think it was an actual physical marker of some sort—one of Merriam-Webster’s definitions for blaze is “a trail marker; especially: a mark made on a tree by chipping off a piece of the bark.”

Fenn had said he thought his hunt could persist for hundreds of years, so his blaze should persist, as well. To me, it had to be something semipermanent, something that couldn’t be moved or washed away or erode easily.

We were walking the site around the gaging station when we found it: a USGS survey marker, noting the siting of this station. The bronze marker was set deep into the rock, the kind of thing that would be there for centuries. This was really something, and Beep and I both realized it, my heart thumping hard.

“If this is the blaze, then we’ve got to look on the ground around here, maybe in the brush, maybe in the river itself,” I told Beep as he scrambled off to look at gaps in the nearby boulders. I looked down again at the marker but didn’t dare get too close. The marker was being guarded by a heinously ugly jet black bug, its exoskeleton like tank armor, crawling slowly around our would-be blaze like a wary sentinel. The beast was half the size of my fist. I felt like we were in his territory, so I slowly inched away, not wanting to disturb this guardian of the sacred marker unless absolutely necessary.

I headed for the edge of the Rio Grande, an area right near the gaging station where rocks and trees overhung the water. I wondered if other Fenn hunters had been by this spot before. It was so close to Fenn’s home in Santa Fe, it seemed like a logical place to look. Searchers on the message boards often talked about bumping into other hunters canvassing the same ground in popular search areas; I didn’t know how popular this was, and we hadn’t seen anyone else out here, but that didn’t mean there weren’t other hunters afoot, vying with us to find the treasure. That coming weekend, hundreds of Fenn hunters would be converging on Santa Fe for the annual Fennboree, a celebration of all things Fenn. They were probably all trying to get a little searching in before the event, just like we were. Feeling a sense of urgency now, I moved forward with purpose toward a cluster of boulders that looked like the perfect place to hide something. Adrenaline started coursing through me as I bought into this, hook, line and sinker. It suddenly seemed so real, all of it. Could something actually be hidden here?

The gaging station hung into the river, so to get around it and to the area with the boulders, I gingerly hopped out onto a few stable rocks perched perilously in the Rio Grande. As water streamed over the bottoms of my shoes, I leaned into the area where the brush projected out over the rocks, pushing aside tree branches and hoping not to fall into the river. My very pregnant wife would not have approved of this behavior.

I craned my neck, looking into the crevices, half expecting a siren to go off and Ed McMahon to show up, telling me what I’d won. Peering in, I squinted my eyes to see something a little less exciting: nothing. Nothing at all, anywhere. There was no treasure chest here. Just a bunch of rocks and running water, the famous river rushing fast and hard, eager to gobble up any who didn’t respect its power.

I carefully hopped back to the shore, where Beep reported he’d found much the same. I was suddenly feeling despondent, that adrenaline high fading as quickly as it had arrived, but Beep wanted to head up the road a little bit farther.

We got back into the car.

I wasn’t even sure what we were looking for now—a blaze, high waters, heck, a fishing spot with brown trout—any of it. What we found instead was a bridge, a fairly large one, where the main road seemed to end before an offshoot forked up into the mountains.

A sign marked it as the Taos Junction Bridge, and there were a few cars and trucks parked nearby, but no people. We got out again to look around. The trail seemed cold, and the sun was starting to settle low in the sky. The water rushed by us, the bridge spanning the spot where the Rio Grande meets another river, the Rio Pueblo de Taos. I wasn’t sure what to do next, so I told Beep I thought we should go home.

Beep was convinced we were on the right track, but he grudgingly accepted. One of his favorite pastimes is predicting outcomes, laying odds on them. Before we’d driven north, he’d put our odds of finding the treasure someday at less than 3 percent. I thought that was wildly generous. But now? Now that we’d started searching the Rio Grande, Beep was putting us at a whopping 10 to 15 percent.

“I’m just so certain now. I know I shouldn’t be. But everything lines up,” he said.

I couldn’t say I shared his sentiments, but it was hard not to get a little bit excited by our first day of work. We had a long drive back to Santa Fe ahead of us, but we were feeling good; for a few hours, at least, we had felt like real treasure hunters, chasing down hunches. There was an upbeat vibe in the car as we turned the Ford Explorer around and left the Taos Junction Bridge and the handful of parked trucks in our rearview mirror. Maybe we really are on the right track, I thought as we raced back to town, feeling like veteran hunters already, capable of tackling anything this chase threw at us.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

One week later, search and rescue personnel would be combing the area around that parking lot in search of a Fenn hunter named Paris Wallace. Wallace had parked his truck there and ventured off to explore the Rio Grande below for the same reason we had: He believed it might hold the key to finding Fenn’s treasure.

Wallace would never be seen alive again.

___________________________________