Forty-eight years ago Francis Ford Coppola released “The Godfather,” thereby cementing a popular conception of the mafia as an insular, clannish consortium obsessed with vendettas and distrustful of the outside world.

In real life, as in movies, almost nobody escaped the mob unharmed. One of the few who managed to leave intact did so by hiding in Hollywood, where, in an odd twist on art imitating life, he played tough-guy roles.

In July 1937, Murder, Inc., the mob’s enforcement arm, learned that an underling named Walter Sage was skimming profits from illegal slot machines installed in resort hotels in the Catskill Mountains, a hundred miles northwest of the New York. Sage would have to pay for his transgressions.

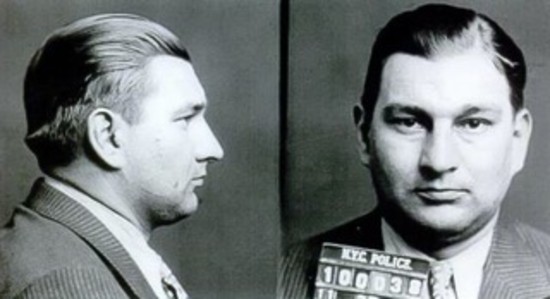

Murder, Inc often assigned assassination jobs to the target’s most intimate friend on the theory that his reassuring presence would dispel suspicions. In this case Murder, Inc sent Sage’s former roommate, Irving (Big Gangi) Cohen, a hulking man with close-set dark eyes and the frame of a heavyweight boxer.

On the evening of July 27, Cohen and a local associate named Jack Drucker picked Sage up at the Hotel Ambassador, in Fallsburg, N.Y., and set off in a stolen green Packard sedan for drinks and dinner. Sage was unaware that an underling named Pretty Levine followed at a discreet distance in a second car. Sage sat in the passenger seat. Cohen and Drucker sat in back. (It’s not known who was driving). Cohen leaned forward to talk with Sage as they wound their way past fields and farms. After four miles or so Drucker quietly unsheathed an ice pick. Cohen wrapped his arms around his best friend’s neck from behind, pinning him to the seat while Drucker stabbed Sage thirty-two times in the chest and neck. He missed once, sinking the ice pick into Cohen’s left forearm. In desperation, Sage yanked the steering wheel, sending the Packard veering off the road. By the time the car stopped hard in a ditch Sage had ceased to struggle.

Cohen’s mind may have been disarranged by his participation in his best friend’s murder. He was seized by suspicion that he was set up as the next victim. It occurred to him that the icepick sunk into to his left arm was no accident. Cohen was speaking to Drucker when he bolted for the woods, his 240-pound bulk sprinting over felled tree trunks. The men called Cohen’s name a few times, then gave up.

Nobody saw Cohen back in Brooklyn. Nobody knew where he went or what happened to him until, two years later, Pretty Levine and a friend went to the Lowes theater in the Brownsville neighborhood to see “Golden Boy,” a black-and-white movie about a violinist named Joe Bonaparte, played by William Holden, who takes up boxing to earn a quick fortune. The two men sat in the dark as Joe prepared for a climactic fight in Madison Square Garden against an opponent named Chocolate Drop. The bell clanged and the boxers engaged—uppercuts, jabs, hooks. A few punches into the round the film cut to ringside reaction shots. The camera lingered for a beat on the unmistakeable bulk of Big Gangi Cohen standing among dark-suited onlookers.

Levine and his friend reported their sighting to the higher-ups gathered in the back booth of a candy store. No, they said, it didn’t look like Gangi Cohen. It was Gangi Cohen. Nobody believed them until they all went back for the late show. If crime doesn’t work out, they joked, we can always go to Hollywood.

***

In the days after sprinting into the woods Cohen had traveled as far from Brooklyn as possible. He landed in Los Angeles where a light heavyweight prizefighter turned movie actor named Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom helped him get small studio parts under the name Jack Gordon. He easily won gangster roles because he looked the part. He appeared in many of the potboilers Coppola drew from when he made “The Godfather.”

Murder, Inc dispatched an agent west to “take care of” Cohen, as they used to say, but the authorities found him first. Brooklyn District Attorney William O’Dwyer telegrammed an arrest warrant with a request for urgent action. On March 18, 1940, three sheriff’s deputies arrested Cohen while he was playing cards with friends in the apartment he shared with his wife Eva and their 12-year-old son, across the street from the Paramount studio lot. At the time he was filming “The Sea Hawk,” an Errol Flynn movie.

“You’ll get a kick out of this,” Cohen told one of the deputies as they handcuffed him. “I played a copper in one picture.”

***

On June 17, 1940, Cohen, who played hardboiled roles in both movies and real-life, blubbered like a frightened child in a Sullivan County courtroom, in upstate New York, as Pretty Levine, the prosecution’s primary witness, described how Cohen helped stab Walter Sage to death. At one point Cohen covered his face with his handkerchief and collapsed into sobs so convulsive that the judge granted a fifteen-minute recess. The next morning’s New York Daily News called Cohen “Big Weepy.”

The jury would have to decide if his tears were sincere or the product of his new acting skills. In his summation, Cohen’s lawyer, Saul Price, asked the jury if they were prepared to send Cohen to the electric chair based on the testimony of a dubious witness like Pretty Levine. Price’s voice broke with emotion. Cohen’s wife Eva, thin and pale, began to cry in the gallery. Cohen himself put his head between his hands and wept.

Price raised his hands and shrugged. “If you have any doubts as to (Levine’s) truthfulness you must acquit Cohen.”

As it turned out, the jury did have doubts. They deliberated for just ninety minutes before acquitting Cohen. O’Dwyer, who had attended the trial, made his way through the courtroom to shake hands with Cohen. “Congratulations, Gangi,” he said. “You took a chance and you won.”

Cohen and Eva returned to their home on North Van Ness Avenue, across from the Paramount lot, where he resumed playing cops and other tough-guy parts. When gangster movies faded from fashion in the late 1950s he found years of work as the double for Hoss Cartright on the TV series Bonanza.

*