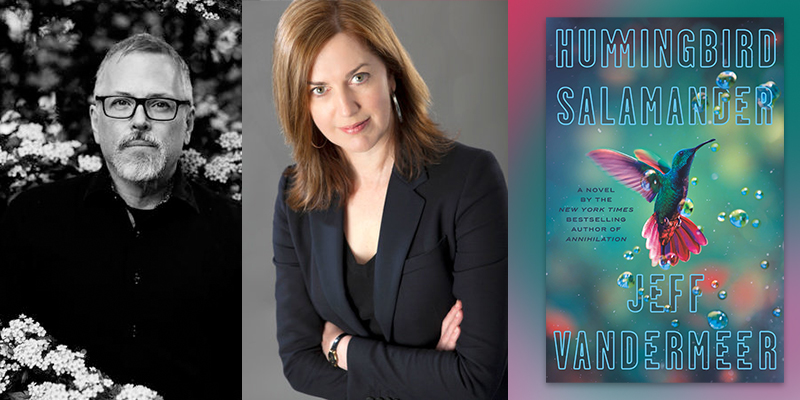

I’ve been a huge fan of Jeff VanderMeer’s fiction since his noir fantasy novel Finch. In the years since, I’ve grown to admire—and envy—his range as an author, along with the depth of his imagination and his ability to send chills down my spine while enthralling me with his prose. His work includes The Southern Reach Trilogy (Annihilation), Borne, and Dead Astronauts. I first met him in London with his wife, Ann VanderMeer, a Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winner and his co-editor of the anthologies The Big Book of Science Fiction and The Big Book of Classic Fantasy. Since then, we’ve reconnected at the Texas Book Festival and over tacos in Austin. VanderMeer is an author I can count on to give me both heart-pounding anxiety and a breathless dose of exhilaration. His new thriller, Hummingbird Salamander, pulls readers into a surprising, heartrending, and riveting story. I got the chance to catch up with him over email to talk about the novel, writing about the environment, and his immersion into genre.

Meg Gardiner: Hummingbird Salamander deals with eco-terrorism, wildlife trafficking, and climate change. What sparked this story?

Jeff VanderMeer: Annihilation in 2014 really opened things up for me in terms of environmental issues. In the sense that the success of the book and its approach allowed me to talk about the climate crisis and even speak to some university environmental science departments. This has included putting ideas into practice, through documenting the rewilding of our yard, encouraging others to make public and private spaces in cities and the suburbs arks for wildlife, through the #VanderWild hashtag and various articles. As well as getting involved in local politics, which I highly recommend as a great way to make a difference on the environment. Vote out the people for the status quo. Find out what local social justice and/or environmental organizations are doing and find a way to help, if you can.

And what all of this did is open up a kind of two-way dialogue. I heard from a lot of ecologists and students that there was a need for immediacy in storytelling about the situation we’re in. As usual, I put that in my subconscious and told my brain “I want to write about nature and the environment more directly.” And one morning I woke up with the character and initial situation in my head. “Jane Smith,” who won’t tell us her real name, being given the key to storage locker with a taxidermy hummingbird in it. A hummingbird that’s extinct. Everything kind of unfurled from there.

MG: You’re known as a speculative fiction writer—science fiction, fantasy, the weird. Hummingbird Salamander, though, is grounded in the present day-ish world. It doesn’t include supernatural elements. It does contain plenty of suspense and action, and draws us into mysteries that revolve around traumatic loss—of family, ecologies, maybe the world. How do you describe this book?

JV: That’s true, but at the same time the Southern Reach trilogy, for example, was set in the real world and the real challenge there was character relationships, how to unfold the mystery—all of the usual stuff in non-speculative books. So I see the “weird” element in Hummingbird Salamander as being about how dysfunctional and strange our reality has become. Sometimes I describe the novel as a thriller-mystery set ten seconds into the future, or as traveling through our present into the near future. Readers should expect a lot of the dark absurdity and environmental themes as well as the usual thing—that I tend to write “messy” protagonists who don’t easily fit into the world around them. The fact is, our reality with its conspiracy paranoia and all the rest tends to affect our fiction, too. So that the present-day is science fiction.

MG: Protagonist “Jane Smith” is a security consultant. In telling the story, she uses an alias and obscures the name of the city where she lives. That helps place the story in the world of tech… and of danger and conspiracy. It also imbues it with a noir aspect. Did you consciously incorporate thriller elements when structuring the novel?

JV: I definitely did. Back when I was writing Finch, a noir fantasy novel, I studied a lot of books on the craft and art of writing thrillers and of writing mysteries. I found the specific applications of craft to this art form fascinating and they wound up influencing Annihilation as well. Similarly, I got a gig reviewing thrillers and mysteries for Publishers Weekly for several years before writing Finch, which meant I had to read and review whatever they sent. I couldn’t choose. When you do it that way you get such a crash course. And I love this genre anyway—it’s something I read for pleasure all the time, including, as you know, your novels, which have been one inspiration. So by the time it came to write Hummingbird Salamander, I was doing so from this reservoir of past experience with these kinds of elements.

Also, I think form has to follow the interiority of the character to some degree, and the inspiration for the set-up, so a psychological thriller just fit Jane as a protagonist. But it’s also true that, as I said earlier, I was seeking an immediacy about climate issues and the puzzle of why a dead woman is communicating with Jane, along with the mysterious forces working against her, allows for a clarity of purpose from which I can hang all kinds of environmental information without it being dead weight. One thing a thriller or mystery does, depending on the subject, is turn information into plot—clues, vital intel on a character, and much more. So the form allowed me to push further in some ways.

MG: As in the best noir tales, Jane is primed to follow a twisting, dangerous path, once the right lure is dangled before her. Where did the inspiration for her character come from?

JV: You know, it just came to me that she was a former wrestler and amateur body builder and that she had a real physical presence. Over time, as I thought about the novel before I started to write, I had a general idea her career was in computers, but that became more precise once I sat down to write. One thing that always struck me about my wife, Ann, is that she had wanted to be a homicide detective in Miami but then took a statistics course in college and decided to become a programmer and then eventually a software manager, instead. And I think that detail got changed and fictionalized for the novel. I also knew Jane would come from a childhood on a small farm, from a dysfunctional family, and that this would still haunt her as an adult. That there would be ways in which she didn’t quite feel like she fit in the world she moved through. Once I knew all of this, I knew she wouldn’t always react to situations in an average or expected way. I knew she might take chances, in part because of her job, thinking her knowledge protected her.

MG: Were there particular challenges in writing this book?

JV: Whenever there’s an environmental element, I have to make sure that what the character thinks, feels, and expresses is what that person would think, feel, or express. Not what I know or what I believe. So it was interesting to follow Jane’s path of having some of her assumptions about the world challenged on the way to her version of an environmental awakening. Also there’s just that kind of pulse or beat you have in certain kinds of noir, a kind of music that you have to follow in the right way. The right path. So I just kept following that beat and if I got off track, I’d go back and start some scenes over. Then there was the whole issue of the pandemic, since the novel is so near future or present-day. Luckily, the distance I had naturally in the novel leant itself to being current without needing to change much to avoid being out of date. I guess the most joy I got was just that once I was in Jane’s head I never left that perspective and I felt so deeply embedded in her perspective that after writing the novel there was a bit of a challenge in leaving that headspace.

MG: I heard that you write your first drafts longhand. Is that an urban legend? What’s your writing process?

JV: Ha! No, it’s not an urban legend. I do write first drafts longhand. I also used to write on an old manual typewriter, before it broke. I loved the physicality of the keys striking the paper. It would slow me down, because I’m a fast typist and that’s not always good for my writing. Handwritten drafts do the same thing. But, basically, it’s like kneading dough for me. I write it longhand, type it into the computer, print it out, rewrite it longhand from that, and just keep doing that until it’s done. Sometimes I do less longhand and I think something about the stark noir aspect of parts of Hummingbird meant I didn’t always use longhand. Sometimes I became un-luddite and used the computer first. But, then, I’ve been known to write notes on leaves, too.

MG: What’s it like having a hyper-accomplished editor working in the next room?

JV: That’s great question. It’s nerve-wracking! No, actually, it’s great. I can ask Ann about scenes in progress. For example, this time since Ann has extensive experience (unfortunately) with a career working in male-dominated industries, she was able to share what the feeling of that was like. Something I didn’t want to fake. And she also is the first person to read a finished draft. Although she will read the novel and not tell me she’s read it, and I have to ask her if she’s read it, and then pull the intel out of her. She says she is just trying to avoid “the interrogation” as she puts it. All my books are dedicated to her because she’s always involved in writing them in some way.

MG: Is Neo satisfied with scrambled eggs, or has he continued to demand more elaborate breakfast menus?

JV: Our cat Neo needs his own detective series. He’s naturally very curious, so I think he’d be good at solving mysteries. Like, “Why aren’t my scrambled eggs ready yet?” Or, “Why can’t I have more salmon?” It is true he might be a bit spoiled, but since he doesn’t have a job to go to, I don’t think it’s doing any harm. He’s been a real blessing during the pandemic, since we’ve been in lock-down since last March. He is definitely a close friend.

***