Thrillers, those beloved and highly consumable escapist pleasures, are often mistaken for immoral fluff. I’d like to suggest the opposite.

Where fiction draws wavy lines toward “morally-correct” conclusions, thrillers fling straight and piercing arrows into the heart of morality itself. How? By displaying catastrophic consequences for “bad” behavior. This is what I call the morality of immorality. Bad behavior shapes the heart of many popular thrillers. A character makes a crucial mistake or commits a crime and the result is a shocking, over-the-top, often violent or deadly outcome. It’s the “scare ‘em straight” teaching method.

Consider the Fatal Attraction screenplay by James Dearden. After a family man, Dan Gallagher, engages in a brief extramarital affair, the woman he sleeps becomes obsessed with revenge. She brings her rage to his front door, and then into his home when she boils the family’s pet rabbit on their stove. The moral lesson is clear: If you have sex outside of marriage, you jeopardize your entire family. “I’m scared Jimmy, and I don’t want to lose my family.” (Dan Gallagher from Fatal Attraction).

Then there are thrillers where bad behavior occurs without overt consequences. The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Hightower comes to mind. Tom Ripley murders his vivacious new friend Dickie and assumes his identity, and his wealth. He murders Dickie’s best friend Freddie to cover up this crime, and he gaslights Dickie’s suspicious fiance Marge—bad behavior indeed. At the end of the book, Tom not only escapes arrest, but maintains the trust of Dickie’s father, who transfers Dickie’s wealth to Tom. Tom sails into the sunset a free man, leaving two dead bodies, a distraught fiance, and a grieving and duped father in his wake.

Does the moral message contained within The Talented Mr. Ripley condone and reward murder? No, because Tom Ripley’s goal is not to kill people. His goal is to be important and accepted. “I always thought it would be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.” (The Talented Mr. Ripley, Patricia Highsmith.) Tom is afraid of being exposed for what he is—an unlikeable loner and a fraud.

While Tom’s violence keeps him safe from arrest, it is at the expense of what he wants most, because he must become Tom Ripley once again. “He hated becoming Thomas Ripley again, hated being nobody, hated putting on his old set of habits again, and feeling that people looked down on him and were bored with him unless he put on an act for them like a clown, feeling incompetent and incapable of doing anything with himself except entertaining people for minutes at a time.” (The Talented Mr. Ripley, Patricia Highsmith.)

At the end of the book, Tom Ripley has failed at his goal, thus there is no reward. His murders have served to further separate him from his own humanity, and thus from his ability to enjoy authentic connections with others. The moral lesson is that murder intensifies human isolation. This isolation condemns Tom worse than any prison sentence would.

It is unclear if the “scare ‘em straight” method works on its audience. Did one man’s dalliance terrify a generation of moviegoers into thinking twice before cheating? Is Tom Ripley’s heartbreaking loneliness the reason we don’t commit murder? Whether or not these stories change behavior or simply satisfy a readers’ sense of moral justice remains a mystery, but what is clear is that these stories are evergreen when it comes to their popularity.

Also surprising is that the moral messages contained within many thrillers lean conservative even as our society grows increasingly progressive. Thrillers hold sacred the family unit, honesty, first wives, virgins, faithful spouses, and animal lovers. Yet these conservative messages are sold to us in sexy, immoral packages, utilizing R-rated lessons to promote G-rated behavior. It is “moral medicine” packaged as entertainment. It would be interesting to examine how these messages change or do not change over time.

If nothing else, thrillers throw readers off their bearings, wildly spinning their moral compasses in search of “true north”. Readers might sympathize with a perpetrator: think Dexter Morgan from Darkly Dreaming Dexter by Jeff Lindsay, or You by Caroline Kepnes, or unknowingly, think Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. Dig even deeper, and you’ll understand that the most important character in a thriller is the reader. The closer a reader aligns with the moral messaging of a story, the more thrilling that story should read for them. If this is true, then one could argue thriller readers are, at large, a wholesome bunch. Would you agree?

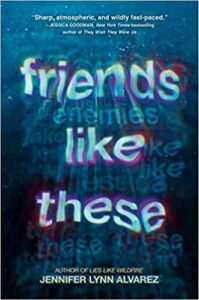

In my latest thriller, Friends Like These, a character seeks revenge on her ex-best friend and her ex-boyfriend—who are now dating each other—and quickly faces dire and criminal consequences. In true thriller fashion, there are clues, red herrings, twists, bad behavior, and . . . the dreaded consequences! You can trust that—like a cat twisting in the air—the story will eventually land on its moral feet, and the reader will leave with the lesson: There is no worse enemy than a scorned best friend.

***