Last fall, as part of the annual Bouchercon celebration of mysteries and their authors, one panel was devoted to discussing a writer who’s been dead for three decades and a character who last appeared in a book when Reagan was in the White House. One of the panelists, Ace Atkins (The Sinners) showed up in a T-shirt that proclaimed: “BASTARD CHILD OF TRAVIS MCGEE.” Immediately the other panelists all clamored for identical shirts. I was one of them.

Now, let me tell you about Travis McGee.

I come from a family of mystery fans. My grandfather was hooked on Perry Mason, both the TV show and the Erle Stanley Gardner novels. My mother couldn’t get enough of Agatha Christie. Growing up, I jumped from Encyclopedia Brown to Sherlock Holmes to Sam Spade.

One day when I was 14, my chain-smoking great-aunt took a drag on her unfiltered Camel and drawled, “I think you’re ready for Travis McGee.”

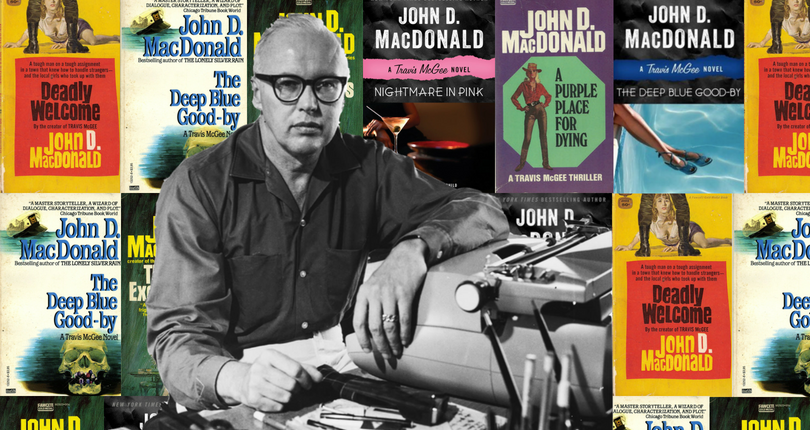

She handed me a well-thumbed paperback called The Deep Blue Good-by, first published in 1964. On its cover was a very shapely woman, topless, but seen from the back. I was a teenage boy, so I gulped and said, “Yes, ma’am, I believe you’re right!”

She gave me three books about McGee, a Fort Lauderdale boat bum/salvage consultant who was catnip to women and a magnet for trouble. That was my introduction to McGee’s creator, the prolific John D. MacDonald, who wrote 500 short stories and 78 books, 21 of them about McGee, his “knight in tarnished armor.”

I soon learned there was a lot more to The Deep Blue Good-by and its colorfully titled sequels (Nightmare in Pink, The Quick Red Fox etc.) than the lurid covers. Unlike the other mysteries I’d read, many of these books were set in Florida, my native state and MacDonald’s adopted home. It had never occurred to me that a place that seemed so sunny could be so full of shadowy characters.

In the McGee series—which concluded with The Lonely Silver Rain in 1985—and many of his other novels, MacDonald wrote about Florida’s beauty, the appeal of nature and the risks of ruining it. He had an MBA from Harvard and had worked for an investment house and an insurance company, so he knew how business worked, how conscienceless and corrupt it could be, how it could turn a gorgeous public resource like a bay into a lifeless ruin for private profit. He had also been a lieutenant colonel in the Army, so he knew about large bureaucracies and how they can grind an individual down.

The more I read, the more fascinated I became. MacDonald’s books weren’t just straight-ahead puzzle mysteries like my grandfather’s Perry Mason books. This author digressed. He quipped. He had a lot to say about a lot of things—particularly about the greed and carelessness driving the bad decisions being made about my state. What he had to say was a revelation to teenage me. I’d spent lots of time hunting and fishing with my dad, as well as camping and canoeing with my Boy Scout troop. Until I read MacDonald, I didn’t realize that the places I’d enjoyed visiting might someday be turned into cul-de-sacs and convenience stores, or that such changes might not be for the best.

My experience with MacDonald’s writing is shared by a lot of my fellow Floridians.

“I read all JDM’s books in my early 20s,” non-fiction author Cynthia Barnett (Rain: A Natural and Cultural History) told me. “My father and grandfather had both read them all and it was a point of inter-generational connection for us. We didn’t agree on many things, but Travis McGee and Florida and rapscallions, we could agree upon.”

McGee’s ruminations on the asphalting of Florida are a big reason why MacDonald’s books still have a life beyond the time when he wrote them.

“His ability to so perfectly capture the shared Florida experience of watching your favorite stretch of wild Florida turn to shopping malls and condos, and indeed the outrage, is what makes him so appealing across generations,” Barnett said.

MacDonald knew this subject first-hand. The Pennsylvania native moved his family from Mexico to the sleepy beach town of Clearwater, Florida, in 1949. Two years later they settled in the more upscale Sarasota, a town full of circus performers and eccentric writers and artists. MacDonald was drawn there by the “softness of the air, the blue of the water, the dip and cry of the water birds, the broad beaches.”

MacDonald lived there until his death in 1986. His house sat on an island called Siesta Key, on a point of land with full water views to the north and south, a place frequented by dolphins and manatees. In between putting in eight-hour days writing in a room over the garage, MacDonald enjoyed boating and fishing. He loved watching what he called “the armada of pelicans” wheeling above the waves. In a panther paw print, he saw evidence that wilderness had not yet been wiped out.

MacDonald became so enamored of his gorgeous surroundings that he became an early and extremely vocal environmental activist, battling dredge-and-fill projects that would harm his beloved Sarasota Bay and later taking on other issues, such as saving the Everglades and stopping the construction of the world’s largest airport in what’s now Florida’s Big Cypress Preserve. Well before the first Earth Day in 1970 made the environment a fashionable cause, MacDonald was bombarding the local paper with letters to the editor and columns, and organizing his neighbors to oppose the forces of what he viewed as greed and stupidity.

“Having made the state his home, MacDonald sensed personal loss when…business and government leaders impaired the quality of life,” Pulitzer-winner Jack E. Davis (The Gulf) noted in a scholarly piece on his activism. By 1979, he was grumbling that the air that once smelled of sweet orange blossoms now was so full of foul emissions it had begun “smelling like a robot’s armpit.”

MacDonald smuggled some of his environmental arguments into his thriller plots starting with snide comments about dredge-and-fill development in 1953’s Dead Low Tide. His non-McGee novel A Flash of Green, featuring a crooked county commissioner pushing a ruinous dredge-and-fill project, has been hailed as America’s first ecological novel. It was published in 1962, the same year as Rachel Carson’s nonfiction blockbuster Silent Spring. MacDonald, who based its plot on a real Sarasota dredge-and-fill plan that he had unsuccessfully opposed, dedicated to everyone who was “opposed to the uglification of America.”

Modern-day Florida writer Tim Dorsey (No Sunscreen for the Dead) calls him “Florida’s Nostradamus. He was writing about protecting our environment long before we knew it was an issue.”

Sometimes life imitated his art. In A Flash of Green, MacDonald created a citizen’s group called Save Our Bay, colloquially called the S.O.B.’s. About a decade later, when yet another corporation tried to get permits to dredge and fill part of his bay, the organization that rose up to oppose it (successfully, this time) called itself by that very same name.

In 2016, the Sarasota County library system held a series of events to salute MacDonald’s 100th birthday, culminating in the unveiling of a plaque in his honor. Each event, especially the last one, was very well-attended, according to librarian Ellen India, who organized them. Meanwhile, the Sarasota Herald-Tribune published a series of columns from such writers as Stephen King and John Jakes about the influence he had on their life and writing.

MacDonald’s grandson, Andrew, said he still fields plenty of queries from readers about his famous ancestor, a sign of how much people still value commentary from so far back.

“I think he remains relevant for people today because he was so far ahead on his side commentary, particularly around politics and the environment,” the younger MacDonald told me. “Maybe there is some reassurance for the reader when we see this mess has been brewing a long time and someone else saw it coming- we were warned.”

MacDonald’s far-sighted concern for the environment marks him as more than just a sharp writer and storyteller, Atkins said.

“He always took on social ills,” Atkins said. “He wrote about the environment, corruption and morality. His characters contemplate man’s place in the world and how dirty little secrets can have a resounding effect on the present. The stories have classic themes…Travis McGee lived at the tipping point of Florida, seeing so much of it disappear and warning us of the future.”

(And yes, Ace gave us all T-shirts. In different colors, just like the McGee titles.)