John Douglas is the OG of criminal profilers. As the lead profiler at the FBI, and now as a consultant, he has helped apprehend some of the worst serial killers and predators in history. As a young agent, he hit upon the idea to do extensive interviews with the worst society had to offer: the evolution of this program is traced in Douglas’s book Mindhunter, which was made into a Netflix series last year. To further his investigation into why criminals do what they do, he’s interviewed the most horrifying murderers in recent history: Jeffrey Dahmer, Son of Sam, Ted Bundy, the Green River killer, BTK—the list is depressingly long.

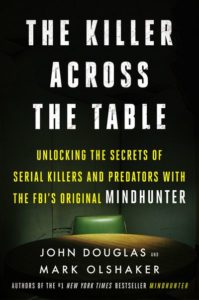

His new book, The Killer Across the Table, talks about some of the lesser known (but still frightening) criminals Douglas has interviewed, as well as describing some of his techniques for getting people to open up—one of the topics we discussed below, along with how his work affected his health, what profilers do to help police, and the advent of forensic evidence.

His new book, The Killer Across the Table, talks about some of the lesser known (but still frightening) criminals Douglas has interviewed, as well as describing some of his techniques for getting people to open up—one of the topics we discussed below, along with how his work affected his health, what profilers do to help police, and the advent of forensic evidence.

John Douglas: I collapsed during the Green River murder investigation. I was sent to the University of Virginia. They were trying to determine what was wrong, and they said, “John, your immune system is so low. If you didn’t have this, something would have happened. You would have had a heart attack, cancer, or something.” Then, they recommended me going to a stress psychologist and I did. They said I was experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder at 38 years of age from all the work. Just the volume and then the nature of dealing with the criminals and dealing with the victims.

Lisa Levy: How long did you take off from work?

Douglas: Just about five months later, I returned to Quantico and had people assigned to me. They gave me more help, but the problem was I had to train these people and it takes two years to get the men and women who are good agents trained for this work. I started with just half a dozen, I worked up to about a dozen of them.

Meanwhile the cases are just piling up due to the successes that we were having along the way, and the successes aren’t just in profiling. Many cases are not suitable for profiling. But we may help in establishing probable cause and a search warrant, or we may develop some proactive technique.

Levy: So you can’t do a full-blown model of the case, but you can help with a piece of it.

Douglas: Yeah, in the Atlanta child killings, we helped develop proactive techniques, and helped the prosecutor cross-examine the subject in the case, Wayne B. Williams. You do things like that or you may be able to testify. What you can testify to is that I’ve looked at this series of cases, say homicide cases or rape cases, and it is my opinion that these cases over here were perpetrated by the same offender.

Why is that? And I get into the fact that not only was it maybe the modus operandi, but it was the signature. What do you mean by signature? Signature is a ritual, something that the offender felt that was necessary for him when he perpetrated his crime. For example, he killed the victim but he didn’t have to pose the victim. He tortured the victim and killed the victim, but he didn’t really have to torture, but torture is the signature that is linking these cases together. At a bank robbery in Texas, the subjects go in and not only rob the bank, they make a victim strip down and then get into various sexual positions, and they take pictures, photographs of him. That is something. I mean, if you want to rob the bank, rob the bank, get the money. But no, they had this need to do that to the victim, so when you start seeing it, even if the cases are coming from one part of the United States to the next part of the United States, you have a very good chance of linking those cases together based upon the signature.

Levy: How much do you think technology has helped you in doing the kind of work you do? It would seem to me it was much harder for police departments across the country to talk to each other before there was an internet.

Douglas: Certainly forensics have improved tremendously. The problem is in 1983 we had a ribbon cutting at the FBI Academy, and we created ViCAP, the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program. It’s a computerized program where police could submit their cases, fill out this form, submit the cases surrounding the case, the victim, and we will enter them into a computer and see if there are other similar cases happening in your part of the country or elsewhere in the United States.

The problem after all these years, they still have ViCAP, but it’s not a very successful program. The reason is that there are over 17,000 different law enforcement agencies in the United States, and it is a voluntary program. It does no good, for example—take New York—if Nassau County participates in the program, for example, but Suffolk County doesn’t.

I’ve been on cases where, first the departments aren’t communicating to begin with, for whatever the reason. They just don’t like each other. They don’t respect each other, or they want to be the ones to crack the case and not this other agency. I wrote another book called Crime Classification Manual, an academic book that I did with really the input of hundreds of investigators. It’s like the DSM. The DSM, Diagnostical Statistical Manual of Psychiatry, only the CCM, Crime Classification. It gives you kind of a chart. Okay, here’s our case. Let’s see what the forensic evidence is. Let’s who the victim is, how the victim was killed. What you do in my job is you classify. Is it a criminal enterprise? Is it a sexually motivated type of crime? Was it a group cause (meaning that there were multiple offenders)? Or is it a personal cause, meaning that the subject and the victims, they know each other.

Levy: Who’s the most prolific killer you’ve caught?

Douglas: It’s not so much me catching them, it’s assisting the police to catch them.

Levy: Right.

Douglas: I think it would be Gary Ridgway of the Green River murder case. But really, it was the police that brought him in. The Atlanta child killings would also be one. I said it back then and I say it today, the police cleared the books of 24 or 25 cases they attributed to Wayne Williams. When I and a fellow agent from my unit went down there, we independently analyzed the cases and behaviorally linked about 12 of the cases. He was convicted of two of the cases. But Wayne Williams did not kill all those victims down there. The case was just opened up again recently with a new mayor down there. The victims’ families, they want to know if it’s not Williams, who was responsible for the deaths?

Levy: How are they going to determine which killings were by Williams and which weren’t?

Douglas: They’re going to go back and just … I wish I was involved in that actually, but they’re going to go back and just look at the forensics they have, and forensics have come so far since 1981 when that crime occurred. They’re going to be doing a lot of the forensics. They’ll do some victimology because for example, there are two young females on that list. One was abducted out of a house. Another was found alongside a wooded area, bound up, panties in her mouth. They weren’t even her own panties, the offender put them there. Those two cases just for starters should not even be on that list, because that’s not a Wayne Williams MO.

Levy: Of the offenders you’ve interviewed, were there any who frightened you or who you felt unsafe around?

Douglas: Never. Well, the worst one was an Aryan Nation Brotherhood member I interviewed. He killed Alan Berg, the disc jockey in Colorado. They brought him in, and he didn’t like me, who I represented. He was huge and I’m 6’2″ myself, but he towered over me. Then, they brought in a correctional officer who towered over all of us. Luckily I had him, and he was in leg irons. But he was extremely anti-me, anti-FBI. I would say I got nothing out of the interview, but I did get something just from that exchange: you cannot negotiate with these people in crimes. They’re very, very difficult … You’re not going to change their way of thinking is I guess what I’m trying to say. He was bad.

But usually it’s just the environment where you do the interviews, going into the prisons, the doors clanging behind you. The noise level in the prisons, it’s just so loud. I don’t trust the inmates. At times, I don’t trust corrections because a lot of the times the corrections get close to the inmates and if something happened, if there’s a hostage situation, they don’t want to be the bad guy. They want to be the good guy to the inmates.

From Mindhunter (Netflix), based on the book by John Douglas and Mark Olshaker

From Mindhunter (Netflix), based on the book by John Douglas and Mark Olshaker

Levy: What were some of the more memorable interviews?

Douglas: When I interviewed Manson, he certainly was an intimidating type of character. He’s about five feet two inches tall, I’m 6’2″. I knew going in he was going to try to dominate me like he did with his followers. And he would sit on top of a rock and lecture to his Manson Family, his groupies. With me, we had furniture in the room, and sure enough when he comes into the room he sits up on top of a chair, so he can look at me, look down at me. I’m on a fact-finding mission, and I want to be Manson’s friend. I want him to trust me. So you don’t challenge him. If he starts coming up with some stories that aren’t quite true because I know I’ve studied the case fairly well. I don’t confront him on it. I’ll laugh, say, “Come on. I know the case. I’ve seen what you’ve done. What are you doing? You’re ridiculous.”

“I’ll set up the interview as very relaxed. Unlike in the movies, it’s going to be a very low lighting kind of room. I’m not going to be taking notes…I’ll set up the interview as very relaxed. Unlike in the movies, it’s going to be a very low lighting kind of room. I’m not going to be taking notes where you see these shows on television, including Mindhunter, they’re taking notes. Well, initially we took notes, and initially we used tape recorders, but then stopped doing it. And the reason is they’ll ask you, “Why are you taking notes? Where you going with those notes? Who’s going to see those notes? Why do you have the tape recorder on? Who are you going to play that to, the warden? You’re going to play it to the warden?”

Levy: So it plays into their paranoia?

Douglas: Yes. You know that going into that, so hey, we can’t use notes. We can’t be taking notes. We can’t be bringing tape recorders in. After Mindhunter aired on Netflix, I got all these production companies calling me saying, “Oh, we want to do a show. We want to use all those tapes that you did with all these people you’ve interviewed.” “I’m sorry, there are no tape.” “There are no tapes?” “No, there are no tapes.” Then, I’ll tell them the reason why.

Levy: Why do you think you’ve gotten so many criminals to open up to you?

Douglas: I don’t believe in self-reporting. These guys, they’ll lie to you. They lie to me. They won’t lie to you if they realize that you have studied their crime inside and out, and you’re not being antagonistic to them, you’re a good listener. You’re not shocked or offended.

“How can you understand the criminal if you haven’t looked at the crime?”I used this statement for years and years: to understand the artist, you must look at the artwork, right? To understand the criminal—how can you understand the criminal if you haven’t looked at the crime? Just because someone commits a rape, there are five different rape typologies. I’ll come up with the type of rapist we’re dealing with, or the type of rapist we should be trying to identify in the case of an unsub or unknown subject case.

Levy: I feel like after talking to you, I understand the books differently.

Douglas: Well, it’s hard to express everything in the book. A lot of people think I’ve just done like two books, I’ve done just Mindhunter and this book. I’ve done a dozen books. Like we said, people are interested in the whys of the behavior of these offenders. But then, they’re also interested in how am I able to keep my sanity? And I tell them, “It’s been very difficult. I nearly died when I was 38 on a serial, on the Green River murder case. I collapsed on a hotel room floor.”