This year sees the 125th anniversary of the birth of Elizabeth Mackintosh. Under the name Gordon Daviot she achieved distinction as a playwright, whilst as Josephine Tey she was one of the finest detective novelists to emerge from Scotland. Far from prolific, Tey produced a mere eight crime novels, but the quality of her work has assured her of lasting renown.

Nevertheless, her name does not feature on the list of members of the Detection Club, founded by Anthony Berkeley in 1930. The Club’s membership list over the years includes so many of the genre’s legendary names that the omission of Tey is itself a mystery. The two of us felt that, as current President of the Detection Club and Tey’s biographer respectively, we ought to investigate the puzzle.

Jennifer’s biography of Tey mentions that there was no record of her ever having been part of the Detection Club. Some people speculated that it was a choice on Tey’s part, seeing her as a loner who did not want to be part of things. This did not fit with the Josephine Tey whom Jennifer has come to know, a woman interested in her family and friends, who happily (if quietly) joined in at public events such as the Malvern Festival.

Tey’s London-based acting friends found it hard to understand why she lived at a distance from the capital and sometimes interpreted that as evidence of Tey being an eccentric who wanted to be alone. The truth was rather different and quite straightforward. Tey was invested in her life in Inverness, where she valued her connections with family and friends, and found time and space to write. Nevertheless, she did place a high value on her English friendships and her writing career, and in discussions during research for the biography, Jennifer heard stories that she and Dorothy L. Sayers had been in communication with each other.

Now, at long last, thanks to Jennifer’s research and the assistance of a number of others, we are able to offer a solution to the mystery of Josephine Tey and the Detection Club.

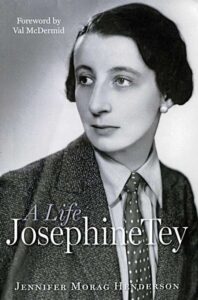

JOSEPHINE TEY, courtesy of Colin Stokes

JOSEPHINE TEY, courtesy of Colin Stokes

In March 1949, Tey was busy writing. The Franchise Affair had been published in hardback the year before and negotiations were under way for Penguin to publish the paperback, Brat Farrar was about to be published in hardback in the UK and serialized in a magazine in the US, and Tey was about to start work on To Love and Be Wise.

At that point, on 16 March, Dorothy L. Sayers (writing in her then capacity as Honorary Secretary of the Club; she would become President in succession to E.C. Bentley later that same year) wrote to Tey to inform her that she’d been elected unanimously to membership of the Club, which had, in Sayers’ words, ‘no object, except mutual assistance, entertainment, and admiration.’ At that time, the Club met bi-monthly, and Sayers suggested that Tey could attend her first meeting and be initiated as a member in May.

A quirk of the Detection Club is, and always has been, that the first time prospective members learn of their election is when they are notified about it. It’s not possible to lobby for membership. Elections are generally conducted by secret ballot, and given that membership numbers are limited and criteria for election are a little idiosyncratic, it’s inevitable that not every prospective candidate is successful. What is more, some people who are elected decide, for one reason or another, not to accept the invitation to join. Membership takes effect once the person has attended a meeting and undergone the famous ‘initiation’ ritual originally drafted by Sayers and Berkeley, with input from Ronald Knox and no doubt others, which has been extensively revised on several occasions over the past ninety years.

Tey replied to Sayers on 19 March, and her opening words made clear her delight: ‘I have an odd feeling that your charming and unexpected letter has altered the foundations of my life.’ She did, however, emphasize that there was ‘one snag’. What was this? Tey explained: ‘I have reached my present age without making a single speech and I have every intention of dying in that virgin condition.’ Given that she lived in Inverness and had various existing commitments, she wasn’t able to make the meeting in May. Although she’d be ‘in town’ (London) it will only be for a short interval ‘between looking at primroses in Sussex and looking at horses in Newmarket.’ However, she added that if the Club would be prepared to put up with ‘a complete dud (in the speech sense) member who nowadays lives mostly in Ultima Thule’, she’d be delighted to accept the invitation.

Tey’s anxiety about public speaking reflects her retiring nature, although, as Jennifer has discovered, Tey did give a short speech to the cast of her play Richard of Bordeaux when it opened in 1932; some of the cast and crew were taken aback, since they had no idea that Gordon Daviot was actually a petite woman from the Scottish Highlands.

Replying on 28 March, Sayers put Tey’s mind at rest about speech-making and said she hoped the Club would have the pleasure of welcoming her into membership before the end of the year. Tey responded with a hastily scrawled postcard (apologizing for ‘this Shavian method of communication’) to thank Sayers and said how much she looked forward ‘to being one of you’. The postcard was signed ‘Gordon Daviot/sorry Josephine Tey’.

And there the correspondence we’ve seen comes to an end.

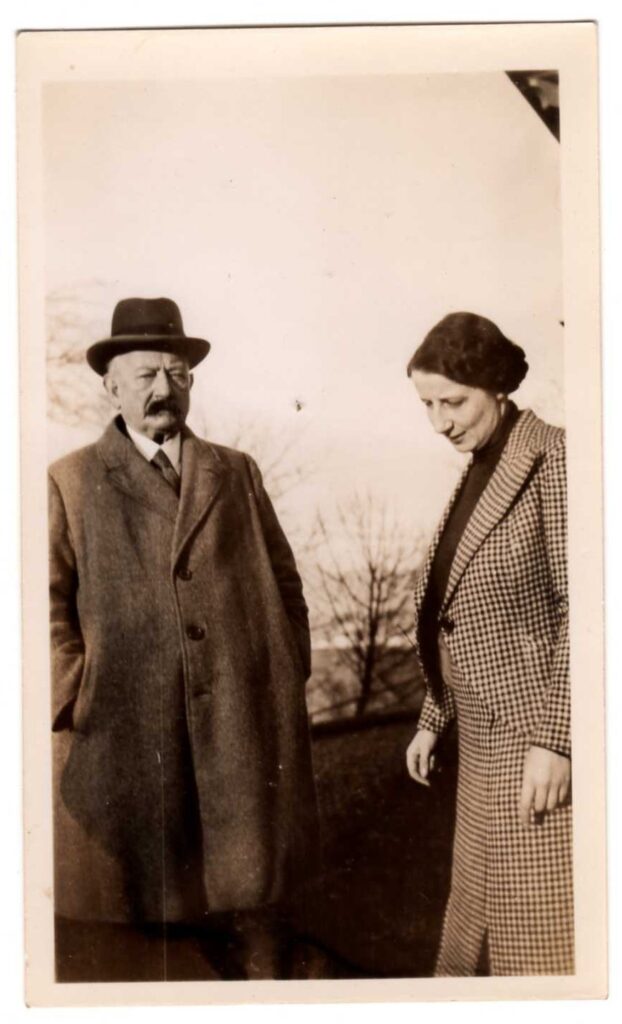

Josephine Tey and her father.

Josephine Tey and her father.

At this point in her life, Tey had been living with her father in Inverness since she had returned home in 1923 due to the illness and death of her mother. By 1949 they had established a routine: twice a year, Tey would go on a fortnight’s holiday, leaving her father to be cared for by a housekeeper. She usually went away for her first trip in springtime. Her holidays were often to the south of England, where she had lived happily, working as a teacher, some years before. Sometimes, her holidays included visits to friends she had made through her writing (such as John Gielgud and Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, both of whom appeared in Richard of Bordeaux), but just as often she made a solo trip, fitting in meetings with non-writing friends, or a visit to one of her two sisters, both of whom lived in England—and including visits to her new (and only) nephew, who was three in 1949. Tey relied on these holidays as respite from housekeeping for her father, which she found taxing.

Tey also arranged other trips away from Inverness for work, and 1949 was a busy year: in addition to her ongoing business with Penguin over paperbacks, her new work and her American serializations, her writing took her to the Malvern Festival, where she had top billing as the star playwright. Her major new full-length play The Stars Bow Down was the main attraction of the festival, which ran throughout August and into September. This visit was a triumph, and Tey wrote to Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies about the social events surrounding the festival, and her delight when her play was chosen as the favorite by the Malvern Gazette. Tey continued to write plays (usually under the name Gordon Daviot) alongside her detective fiction, and had steady success, though nothing that rivaled the days in the 1930s when Richard of Bordeaux was a smash-hit, running for over a year in the West End. The Malvern Festival, however, showed that her playwriting was still highly respected, as well as popular.

Tey was accompanied at Malvern by her friend Caroline (Lena) Ramsden. Tey had known Lena since her first days as a playwright in London, and they met regularly, if infrequently. Lena remembered that, although Malvern was a success and they took in several shows and the related socializing, Tey was also particularly glad to spend time resting. Tey’s father, Colin Mackintosh, died the following year, and his final months of illness were stressful for his daughter. Colin was an active man, a keen angler who ran a successful fruit and vegetable business. However, towards the end of his life he became increasingly frail: he relied on his two shop assistants, and, although he dressed smartly each day to go to work, as one of his friends said, ‘his gait was gone’.

Lena (centre) and Tey (right) at the Malvern Festival

Lena (centre) and Tey (right) at the Malvern Festival

Despite her domestic preoccupations, Tey continued to write at an almost frantic pace. She published at least one book a year at this time—some involving extensive research—as well as short stories and short plays. The plays were being regularly performed (some locally with Tey watching in the audience), while Brat Farrar was filmed for US television in 1950, and the production of the British film of The Franchise Affair was under way.

Her surviving correspondence includes letters about paperback editions, serializations, reviews and fan responses, in amongst family matters. Her father’s death in autumn 1950 left several things that needed to be sorted out, not least the decision of what to do with the family business (both the shop and the flats above, which they rented out). Her publishing schedule continued and, although she managed at least one short holiday to visit old friends, it is easy to see why she had no time to take up the invitation to be initiated as a member of the Detection Club in London.

By October 1951, Tey finally managed to visit her sister Moire in London: she had admitted the strain of her father’s death had tired her out, but Moire was shocked to see just how ill her older sister actually looked. In fact, Tey herself was already suffering from her own final illness. Moire persuaded her sister to see her own doctor, but unfortunately an exploratory operation showed that there was little that could be done. Tey had only meant to leave her home in autumn 1951 for a short break; in fact she never returned. Josephine Tey died, of cancer, at her sister’s house in London on 13th February 1952.

The sad truth is that Tey never managed to attend a Detection Club dinner or be initiated into membership. Jennifer has no doubt that, had she lived, Tey would have enjoyed the meetings very much. She described Sayers’ invitation as ‘charming and unexpected’ and the invitation itself a ‘secret satisfaction’ that she would pride herself on. During the Second World War, the Detection Club had ceased to hold meetings and teetered on the brink of extinction, but Sayers’ vigor helped to infuse it with new life and in the years just after the war, a number of new members, including such leading lights of the genre as Christianna Brand, Cyril Hare, Michael Innes, Edmund Crispin, and Michael Gilbert were elected to membership. Tey had spent little if any time with fellow crime writers and she would surely have relished the chance to get to know some of her most gifted contemporaries, as well as towering figures from the previous generation such as Sayers and Agatha Christie.

We believe that the brief correspondence Jennifer has uncovered provides further evidence to back up the picture she painted of Tey in her biography: not a loner, but a woman with many friends, a strong commitment to her family, and a delight in and passion for her writing. Finding the letters—with their unusual turns of phrase written in her scarcely decipherable handwriting—has given us the chance to fill in one more tiny piece of the mystery of her life as well to find an answer to one of the manifold puzzles of the Detection Club. The correspondence, viewed in hindsight, strikes us as poignant, but how delightful it is to hear once again the distinctive voice of one of detective fiction’s most gifted writers.

***