“I will stand on your eyes, your ears, your nerves and your brain and the world will move in any tempo I choose.” — Marshall McLuhan, paraphrasing the modern Archimedes

Article continues after advertisement

One cloudy day last October, a muscular young man wearing a cowboy hat and carrying a guitar walked up to the US Customs and Immigration station at Brownsville, Texas, and looked uncertainly about him. He was obviously somebody’s hard-times cowboy, and they had not treated him right South of the Border. “How long you been in Mexico?” asked the customs man. “Too damn long,” the cowboy said.

He was Singin’ Jimmy Angland, he explained, and he had been down there to play a little old country music gig and damn if the Mexes hadn’t laid him out and cleaned him. Hell no, he didn’t have no papers. He didn’t have no money neither. Why, he didn’t have nothin’. ’Cept (pat, pat) his geetar. Yep, the women and the margaritas and the streets of Matamoros had laid Old Singin’ Jimmy low and all he wanted out of fortune was into God’s country and then home to good old Boise.

Boise, yessir, that’s where he was born. Boise, Idaho.

Thus, her maternity stirred, the republic reclaimed a bruised offspring, and Ken Kesey, “freshest, most talented novelist of his generation,” creator of a New Aesthetic, diabolist, dope fiend, and corrupter of youth, passed the brown bank of the Rio Grande to his native soil.

He had not been in Mexico overnight to play country music. He had been there since the previous January, and he had gone there concealed in a truck after being arrested for the second time on charges of possession of narcotics.

Kesey is sitting in the garden of the Casa Purina when Des Prado bounds through the adjoining lumberyard crying, “Battle stations!” Des Prado is a young man of vaguely Okie origin who gives the unmistakable impression of having spent a great deal of time on Highway 101. He has also done some time in the can, along with one hitch in the navy and one in the marine corps, so he can shout “Battle stations!” with professional zest. And, indeed, something like a combat situation seems to be developing.

There is a dapper Mexican lurking in one of the bungalows under construction across the road. The Mexican is equipped with an elegant and complex camera and is covertly taking pictures of the house and its occupants.

One of the Pranksters has seized a camera which is even bigger than the Mexican’s and is pretending to photograph him, although there is no film in the Prankster’s camera. The Mexican lowers his and looks thoughtful. He is about thirty, casually dressed in the style of the Mexican tourists who regularly come down from Guadalajara to vacation on the Colima coast.

Kesey sits tight in the yard, a baseball cap pulled low over his eyes. There is a possibility that the man with the camera represents the press, but it is more likely that he is a policeman or an advance man for the American bodysnatchers.

Babbs and George walk across the road and hail him. He is now making awkward conversation with the Indian laborers who are building the bungalow. He will not look at the Americans or reply to them. The Indians are clearly embarrassed at the turn things have taken. Some of them have removed their hats. The camera man answers no questions in any language. After a while he gets into a white Volkswagen parked down the road and drives off. It is the same car that has been seen regularly on the road.

The siesta hour passes tensely. Everyone has assembled at the main house for desultory speculation on the stranger’s intentions. A few optimists express confidence that he will turn out to be a journalist, but this is not the prevailing opinion. Kesey leans against one wall sipping Coke. Every now and then he looks out the window.

When siesta is over Kesey looks out of the window again and sees that the man with the camera has come back. He has come directly to the house and is standing before the door, looking about him with an amiable expression.

Kesey turns and walks into a room where Faye is making Prankster costumes on a sewing machine. They exchange looks, say nothing.

Two or three Pranksters go outside to say hello. One of the Pranksters who goes out is Neal Cassady of song and legend, the companion of Kerouac and Ginsberg in the golden days of Old San Francisco. He has been a sidekick of Kesey’s for years, functioning as chief monologuist and Master Driver for the Acid Test. Now, without a word (most unusual for him) he walks into the road and constructs a little brick target. He had been carrying a six-pound hammer in his belt for days, and he begins to throw his hammer at the target with a great deal of accuracy and control. The dapper Mexican watches Cassady’s hammer-throwing as though he finds it charming. Three other Pranksters are standing around him and they are all taller than he is. Babbs is much taller than he is. He seems to find this charming as well.

He has learned English during the siesta.

“Well,” he says, “I guess you guys were wondering what I was doing out there with the camera.”

Cassady continues to throw the hammer, but now he accompanies the exhibition with a rebop monologue. When there is no one else around, Cassady practices his routines with a parrot named Philip the Hookah. Philip and Cassady discuss automobiles or books of current interest, and since Philip is rather a nonverbal parrot, Cassady does most of the talking. Occasionally, the question arises of what to do with a parrot who will talk like Neal Cassady. Kesey suggests that it would make an Ideal Christmas Present.

“Um yass, quite indeed,” Cassady says, retrieving his hammer. “Quite a setup, yaas, yaas. Bang, bang, bang,” he sings, “bang, bang, went the motosickle.”

The dapper Mexican tells an astounding story. He is from Naval Intelligencia. He is looking for a Russian spy whose description is incredibly like Kesey’s. The Russian spy is spying on the coast of Mexico. Occasionally, Russian ships appear off the bay and they flash lights to him. Russian spies are Commies, the man explains, and mean America no good. The Pranksters are Americans, no? Ah, the man likes Americans very much indeed. He hates Russians and Commies. Might the Pranksters assist in investigating this nastiness?

Ah, now the dapper Mexican sees musical instruments lying on the porch. The Pranksters are musicians, are they not? He seems to find this charming as well. He is watching Cassady’s hammer from the corner of his eye. And how long have they all been in Manzanillo?

*

Kesey stands in the room with Faye and the sewing machine. Faye continues to stitch costumes from the forthcoming Manzanillo Acid Test while Kesey looks through the blinds.

Faye Kesey is a woman of great beauty, the sort of girl frequently described as radiant, possessed of a quiet vivacity and a dryad’s grace. It is said that the meanest cops refrain from giving Kesey’s handcuffs that nasty extra come-along twist once they’ve seen Faye. Fourteen years ago, she and Ken were steadies at Springfield High, and they have come a long way together since. Her name was Faye Haxby, she was a dreamer, and she was of the legendary and heroic race of women who, appearing delicate and fragile as ice cream swans, were yet prepared to accompany some red-eyed guzzling oaf over frozen passes and salt flats, mending axles, driving oxen, bearing children and nursing them through cholera. Faye has never driven oxen, although she can be a handy mechanic, but she has come over some strange passes in some funny mountains and, with Kesey, she has been out in all the weathers.

___________________________________

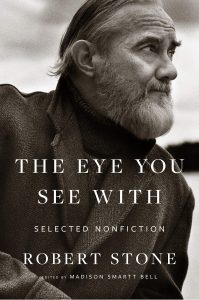

You are reading “The Man Who Turned on the Here,” from

THE EYE YOU SEE WITH: Selected Nonfiction by Robert Stone,

edited by Madison Smartt Bell (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020)

___________________________________

Faye leans forward over her machine for a look at the man with the camera, smoothing out the colored cloth on the table before her.

Kesey watches the Mexican intently, trying to gauge his size, weight, intelligence. He does not know what will happen or what he will do. There is a little song he likes to sing, a cowboy-style ballad called “Tarnished Galahad.” It has that title because a judge in San Francisco so referred to him when he disappeared and Mountain Girl remained in the coils of the law…

He accepts the turns of the outlaw game, but he does not want to go to jail. He is not the type.

*

Just beyond the doorway, the agent with the camera is still talking Foreign Intrigue. When his conversation with the Pranksters lags, he revivifies it by asking questions.

Now it is Babbs’s turn to be uncommunicative.

How about him, the agent wonders. Does he play a musical instrument?

Babbs nods his head affirmatively.

The agent looks him in the eye. In order to do this, he must bend his head backwards and stare almost straight upward. So, the agent says, Babbs prefers not to talk. He prefers simply to watch? He wants to just listen?

Babbs nods and scratches his nose.

Cassady is still performing the hammer throw. Babbs belches. The Mexican agent smiles the grim smile of Montezuma.

But he does not go away.

*

Inside the house Faye sews and Kesey watches. It is now a year and a half since the night when several varieties of law enforcement officers, human and canine, dashed into his house in La Honda to arrest him and thirteen of his friends on charges of marijuana possession. The cool Mexican operative outside is only the latest in a long procession of agents, DAs, sheriffs, snoops, troopers, finks, and detectives who have peopled his fortunes since 10:30 p.m. on the night of April the twentythird, 1965.

Kesey recalls finding little piles of cigarette butts and Saran Wrap on the hillside across from his property several times during the weeks preceding the raid. He had, he says, taken all possible precautions against being accused of marijuana possession. Nevertheless, on that night the officers struck. Kesey says that he, Mountain Girl, and Lee Quarnstrom, a former newsman, were painting the toilet bowl in the bathroom when Federal Agent William Wong sailed through the door, clapped a Federal Agent lock around his neck, and commenced to beat on him. (The bathroom at Kesey’s was—and thanks to the simpatico sensibility of the house’s present tenants, remains—a remarkable pop composition. Much painting and pasting was done on it at all hours.) The police maintain that Kesey was trying to flush his marijuana down the toilet.

A fracas ensued, police guns were drawn, an alleged attempt was made by one of the Pranksters to grab a deputy’s service revolver. The occupants of the house were collared, busted, and taken away. Faye Kesey and the Kesey children were off visiting relatives in Oregon at the time of the arrest.

“We’d been warned by three people to expect a bust that Saturday night,” he says. “Not a bad trip if you’re expecting it.”

Ken Kesey has always maintained that the bust was queer. “We’d been warned by three people to expect a bust that Saturday night,” he says. “Not a bad trip if you’re expecting it. You can set up to film and record the cops’ frustration. You can even have your lawyer forewarned. But some way, they boxed us and showed up a day early. They blew our cool for a while, I have to admit. I’m in the bathroom with Mountain Girl and Lee. Page is standing in the bathroom shaving. Other people were out sewing, working with tapes, wiring, and like that. Suddenly I got a guy beating on me from behind and chaos all around. Babbs snatches him off me onto Page, who falls on his back in the tub. Then follows the whole search, question, banter, and looking ceremony. Other events happened that I tell no more because they have been so often sneered at as likely stories from one side—or nodded at as ‘what else can you expect from those bastards’ from the other. Like the business of painting the toilet, a beautiful double-edged paradox. One side: Okay, but why would you just happen to be painting the can—the most likely place for a man to be disposing of contraband just when the cops busted in? Other side: Okay, but if they were watching and waiting for the best chance to make a good case, wouldn’t they wait for the most incriminating scene to bust in on? And this I believe is the true price of justice—the amount of time wasted justifying.”

The net took Mountain Girl, Des Prado, and Neal along with Kesey and various other Pranksters. The “contraband” assembled by the arresting officers ranged from “one disposable syringe” to “one Western Airlines bag” and included one pint jar and two and a half lids of grass in addition to “marijuana debris.”

One of the principals in the first Kesey arrest was Agent William Wong of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the officer whose flying tackle opened the Battle of the Bathroom. Agent Wong, who is no longer with the bureau, was then working as Federal liaison officer with the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Department Narcotics Division. Wong seems to have become convinced that Kesey was, in addition to being a novelist, a dealer in both marijuana and heroin on an international scale—in any case, he seems to have conveyed this conviction to officers of the county. Just how the Federal presence was introduced into the case is a question that no one involved feels quite able to answer. Some local detectives remember a story that Wong had been working on a heroin case in the area and had come to believe that Kesey was connected with it. Kesey’s lawyers aver that Wong told one of the girls he was grooming as an informer that he believed it was Kesey’s practice to lure girls into his house, get them “hooked,” and then sell them into prostitution.

According to a San Mateo officer, Wong, as Federal liaison man, would frequently drop by the bureau to “bullshit.” The Great Raid seems to have developed from one of these “bullshit” sessions, more or less as a law enforcement caper. And there are persons officially connected with the legal apparatus of San Mateo County who feel that Kesey’s prominence as a novelist and “nonconformist” was not wholly unconnected with the zeal with which his arrest was sought and obtained.

According to the affidavit submitted by the police to obtain a search warrant, Agent Wong was working “undercover” in the North Beach area of San Francisco. In what must be imagined as a low dive frequented by twilight figures without hope, he chanced to overhear the following remarkable conversation:

First Male: Hey, man, did you hear?

Other two persons: What?

Said First Male: At Kesey’s. La Honda, man — a swingin’ pad!

Other two persons: Yeah! Yeah!

The said persons continued to address each other enthusiastically in this manner; the connoisseur will recognize their frenetic mode of speech as the argot of the so-called hipster. Agent Wong, who doubtless does a great deal of listening, seems to possess a gifted amateur’s ear for dialogue, for here again the imagination takes wing. One pictures the agent, inconspicuous as hell; perhaps his hat brim is pulled low across his countenance, perhaps he counterfeits the stupor of narcosis. In the next booth sit the said persons—and, man, you know how they look. They wear berets and sandals, the girl has stringy hair, and like all three of them are carrying a set of bongo drums.

In any case, as the incident is rendered in an affidavit, the first male conveys to others, in the colorful speech to which he is given, intelligence that Agent Wong interprets to mean that Kesey is going to have a party at which dope is served.

Kesey, whose point of view is admittedly subjective and who is perhaps overly given to regard comic strips as vehicles of contemporary reality, professes to believe that this conversation never took place. He holds that Agent Wong lifted the whole number from a recent installment of Kerry Drake.

After relating the agent’s North Beach adventure, the police affidavit goes on to record the alleged statement of a coed who reportedly admitted to officers that she has been “furnished” with marijuana by Kesey, and the account of a surveillance mission during which the police encountered several persons who appeared to be under the influence of a “narcotic, dangerous drug or other stimulant.” The document also records the police’s belief that Kesey was a drug dealer, on the evidence that “said Ken Kesey has written two books, one dealing with the effects of marijuana and one with the effects of LSD, namely Sometimes a Great Notion and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The point seemed to be that Kesey was so confirmed a dope pusher that he felt able to devote his spare time to enriching the literature of narcotics, perhaps with an eye toward drumming up a brisker business.

Signatory to the affidavit and a participant in the raid and arrest was Deputy Sheriff Donald Coslett, a pleasant, crew-cut young man whose office is decorated with assorted buttons of the kind favored by youthful narcotics offenders, examples of psychedelic art, and a Ken Kesey for Governor sign. Deputy Coslett is what might be termed a “head buff,” and it is fitting that he should be such, for he is assigned to the Narcotics Division of the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Department. At the time of Kesey’s arrest he had served some ten months on and off as a narcotics officer and attended a Federal training course for narcotics officers. As a result of his training and experience, the deputy had a simple method for detecting probable violations of the narcotics laws.

“Whenever you get a person who has a bohemian-type house,” he declared, “weird paintings on the wall, nothing made out of coat hangers hanging from an oak tree, and people around banging the bongos all night — nine out of ten somebody’s blowing grass.”

*

It has been a year and a half since Kesey bolted, and now they are back. The Mexican with the camera means he has been found, or is about to be found.

Kesey peers through the window, thinking of Lenny Bruce. (“Bruce was courted to death,” Kesey says. “He got tripped out on the law as though that would help him.”) Kesey will not let them court him to death. He will do something they do not expect, something superheroic.

Babbs and the Mexican walk off down the road together. Kesey waits a few moments, borrows someone’s hat, and goes outside cautiously. One of the Indian workmen in the bungalow across the road makes the sign of the slit throat and smiles sadly. Kesey waves.

He walks down the road, his shoulders thrown back, his pace determined. With the postman’s whistle around his neck he looks like a soccer referee about to make an unpopular decision.

A friend walking with him remarks that this latest of cops is pretty cool. Kesey agrees. The cop is very cool, he has talent. The thing would be to fuck him up.

“Remember the Casablanca routine?” the friend asks. “Humphrey Bogart? Claude Rains?”

“What was that?” Kesey wants to know.

Kesey’s friend does the Casablanca routine. Claude Rains is a Vichy policeman. Humphrey Bogart is Rick, the owner of Rick’s. He’s in trouble with the Vichy police for his suspected Allied sympathies. “Why did you come to Casablanca?” asks Claude Rains. “For the waters,” says Bogart. Rains is urbane but puzzled: “But there are no waters here. We are in the desert.” Bogart tells him, “I was misinformed.”

“Yeah,” Kesey says.

He looks around, surveying the quiet beach. When they come, he thinks, they will materialize out of the sand, they will scamper down from the palm trees, they will emerge from lidded baskets holding tommy guns. Perhaps they will have dogs again.

*

When Kesey was arrested for the second time, it was on a rooftop in North Beach. On that occasion, fortune dealt Kesey a slice of whacked-out reality exceeding the most freaky delirium he had ever dispensed at the Acid Test. He was so impressed with it that he decided to compose the event into a scenario.

*

It was the night before the Trips Festival Acid Test. Kesey and Mountain Girl were free on appeal bond and plotting the doings. They got together on the roof. Someone didn’t like the sound of falling gravel and called the cops.

The cops went up and found a cellophane bag of grass near their reclining mattress. Kesey attempted to fling the bag off the roof. One of the policemen attempted to prevent him and a wrestling match ensued. Kesey, having been an All-American wrestler at good old Oregon U, looked like a winner. The other cop thought everything was happening too close to the edge of the roof and drew his gun. The match ended with the police in possession of their evidence, and of Kesey and Mountain Girl.

It was at this point that Kesey decided he had detected a trend. A short time later, his Acid Test bus was discovered abandoned near the hamlet of Orick, in far northern California. Inside the bus was an eighteen-page letter that began, “Last words. A Vote for Barry is a Vote for Fun. Wind, wind send me meee not this place though, onward . . .”

The letter proceeded to convey Kesey’s respects to the principals in his life and career, and went on, “Ocean, ocean, ocean, I’ll beat you in the end. I’ll go through with my heels your hungry ribs . . .”

As Kesey sped south toward the border, he might have heard what Tom Sawyer heard on his disappearance, for the press lost no time in firing cannons over his wake. Everyone seemed to believe him a suicide except those who had heard otherwise, and this category included practically everyone concerned. All agreed it was a Prankster’s Prank.

*

“Hey,” Kesey calls to the people of the house, “where’d they go, Babbs and the Mexican?”

“Up the road,” someone says. “They went off to the Hawaiian joint for a beer.”

Things have taken a Prankster-like turn. The agent has not arrested anyone, but instead he has gone with Babbs to an elegant Polynesian-style roadhouse. Kesey looks around and sees the margin of reality widening.

The agent has not arrested anyone, but instead he has gone with Babbs to an elegant Polynesian-style roadhouse. Kesey looks around and sees the margin of reality widening.

“All right,” he says. “Let’s go do that Casablanca thing.” The Mauna Kea is quite the right place. It has thatch and palm trees, it has little tables with coconut candle holders. It has a bamboo bar behind which there is a tank of gorgeous tropical fish and a fat bartender who wears a loud sport shirt. Continental music purrs from the leafy loudspeakers. There is even a beaded curtain to glide through.

The Mexican agent has bought two beers; he and Babbs are sitting at the bar, sharing a small plate of spiced shrimp. Kesey waits before the beaded curtain and measures the scene.

He will be Humphrey Bogart. The Mexican agent is no Claude Rains, but he will do for the smooth foreign cop. Kesey eases through the beadwork, slicing it with the edge of his hand.

Babbs and the Mexican agent are now on speaking terms; the agent is buying beer and telling stories, presumably naval yarns. He looks up with interest as Kesey joins them on a stool.

“Hi,” says the agent, “how are you?”

“Well, just fine,” Kesey says.

Babbs introduces him as Solomon Grande. The Mexican’s name is Ralph.

“Grande?” he inquires. “Grande? What is that? French?”

“American.”

“Fine, fine,” says Ralph. He is quick to buy another beer. He seems in a mood to drink beer himself.

“A guy in Sinaloa,” Ralph declares, apparently resuming an anecdote, “one time swears he’s going to kill me. He believes he’s more man than me and that he could do it. One time I’m in the office and the chief says to me, You know what? Old what’s-his-name in Sinaloa wants you to come see him. He wants you to be the godfather of his child.

“I say, Good — I’ll go.

“The chief says, Man, you’re crazy. He wants to kill you.

“I say, He can try.

“I went. I’m godfather to his child. Now he’s my compadre. He was going to kill me. He’s my compadre now.”

“Huh,” Babbs says. “Was he in trouble with the navy?”

“Naw. He was a big dealer in marijuana. We sent him up.”

Kesey frowns. “Marijuana, huh?”

“Yeah. You know about that? Marijuana?”

“Yes, I have heard of it,” says Kesey. “But I don’t believe it’s as much of a problem in the States as it is down here.”

“Is that right?” the agent asks. He is very cool indeed. “But I thought it was.”

Babbs and Kesey shake their heads furiously.

“No, no,” they assure him, “it’s hardly any problem at all.” More beer and more shrimp arrive. Someone else pays for it and the Mexican agent is much put out. He is sensitive about his salary.

“So you investigate dope-taking too?” Kesey asks.

“Sure.” He goes into his pocket and produces a badge emblazoned with the rampant eagle and struggling snake. He is a Federale, and his badge number is One. He is Agent Number One.

“Numero Uno,” Kesey says. He looks at the badge. Babbs whistles softly through his teeth.

“Do you have a license to kill?” Babbs asks.

Agent Number One cocks his head in the Mexican gesture of fatality.

“Sure,” he says. “Sometimes people try to escape.” Someone buys another round of beer. Agent Number One seems to grow very angry.

“Don’t do that again,” he tells them. When that round is over, he buys the next.

He tells them that at the office they call him El Loco. They call him that because he takes on the cases that no one else wants, the cases you really have to be tough to handle. It was he, he informs them, who followed Lee Harvey Oswald through Mexico City. In Puerto Vallarta, he met Elizabeth Taylor in the course of a secret investigation.

“There was an American who was one of the movie company stooges,” Number One recalls. “He tells me that it’s impossible for me to see her.”

He leans forward, almost snarling into Kesey’s face. “I told him, You don’t tell me it’s impossible!” Babbs and Kesey nod in spontaneous approval.

“By the way,” the agent asks, “have you ever been in Puerto Vallarta?”

“No,” Kesey says. “And I’ve always regretted it.”

“You’d like it,” Agent Number One says. “It’s beautiful.” There is a short pause as everyone sips their beer and takes a reality break.

“By the way,” Babbs begins, and commences to tell outrageous stories involving Russians and people who appeared to be Russians whom he has encountered in and around Manzanillo. There have been many. Sometimes it has seemed that there were more Russians than Mexicans about.

Agent Number One receives the intelligence soberly. He keeps saying “Wow!” and seems always about to write something in his book. Kesey joins in telling of his encounters with Russians.

“Wow!” Number One says. He tells them that this information will set one hundred and fifty Federal agents in motion.

“Wow!” Babbs says. “A hundred and fifty!”

“Sure,” the agent says.

Des Prado comes into the bar and the Federale buys a final round of beer for everyone.

Kesey and Babbs present the agent with one of their Acid Test cards. Number One looks at it incredulously.

“Acid?” he inquires. “Acido?”

“Sure,” Babbs says. “We say that if you can stand our music, then you’ve passed the Acid Test.”

“Wow!” the agent says.

They walk outside and stand in the sun beside Number One’s white VW. There will be an Acid Test at their house on Saturday, the Pranksters tell him. He is invited. If the hundred and fifty other agents have nothing special to do that evening, they are invited as well.

Agent Number One looks at them strangely and says he will try to make it. Also, he has one favor to ask. Might he take their picture? For his collection. He already has Elizabeth Taylor’s.

Kesey shrugs, confounded. Why not? Babbs, Kesey, and Des Prado throw their arms about each other’s shoulders and strike superheroic poses. The agent, all business, photographs them.

He gets in his car and Babbs climbs in beside him. They are going for a drive so that Babbs can show him all the places where the Russians have been seen.

Kesey and Des Prado walk back down the road to the house and sit down outside.

After a while Babbs appears, grinning.

“What a great cat!” Babbs says. “How about that guy?”

“Definitely a man with something going for him,” Kesey says. “Definitely.”

—In One Lord, One Faith, One Cornbread, 1973

(a version also appeared in Free You, 1968)

(Featured image:Yuccaland—Chihuahua, Mexico, William Henry Holmes (1846-1933)