Excerpted from the introduction to

Beyond the Thirty-Nine Steps: A Life of John Buchan, by Ursula Buchan

__________________________________

‘Better than the book’ was John Buchan’s verdict when he first saw Alfred Hitchcock’s film, The 39 Steps, in 1935. This was not simply an example of his famous courtesy and good nature. Rightly, he reckoned his novel of 1915 to be a modest accomplishment in the context of his many other achievements. After all, he was just about to take up his appointment as Governor-General of Canada, earned after a hard slog in the House of Commons, with the title of Lord Tweedsmuir. However, it is that film which, more than anything else, has kept the book and its author in the public eye ever since.

John Buchan’s career as a writer, one of the best-selling of his day, would have been remarkable, even in someone who had done nothing else. He wrote more than a hundred books, including twenty-seven novels, six substantial biographies, a monumental twenty-four-volume contemporary account of the First World War, three works of political thought and a legal textbook. There were also dozens of poems and short stories, and about a thousand articles for newspapers and periodicals. As well as a writer, he was a scholar and an antiquarian and, at various times, a barrister, colonial administrator, journal editor, publisher, director of wartime propaganda, Member of Parliament and imperial proconsul. He had been a skilled and intrepid mountaineer in his youth and was always a dedicated fisherman and a prodigious walker. And he did all this while suffering from debilitating illness for most of his adult life.

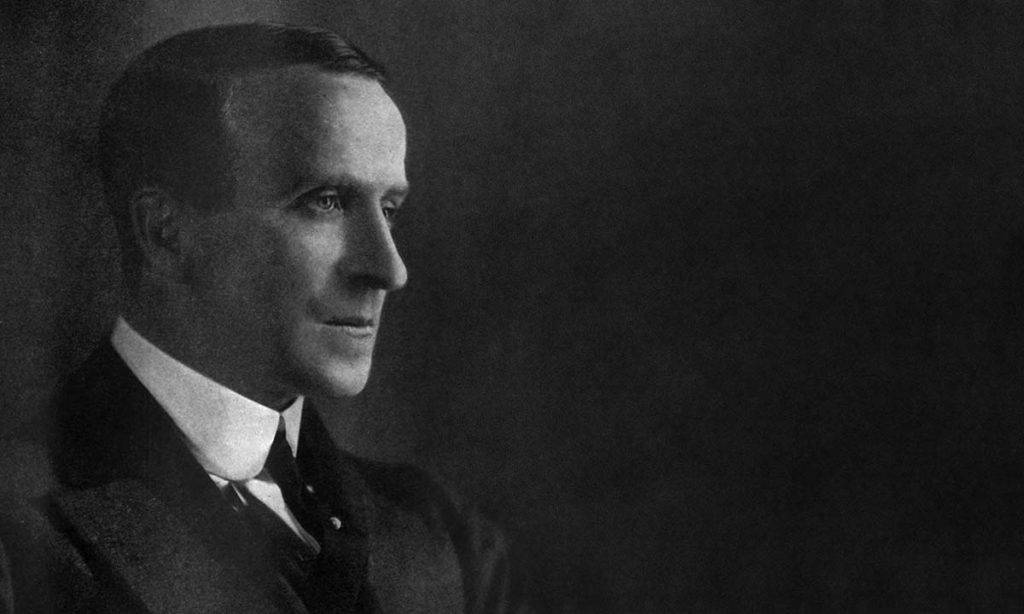

Author John Buchan

Author John Buchan

In his private life, John Buchan had a gift for friendship, with a breadth of sympathy and a willingness to see another’s point of view that endeared him to people, while inhibiting his political career. As a result of his upbringing and education, he was at ease all his life with shepherds and ambassadors, coal miners and prime ministers. This ability to transcend boundaries, even in stratified Edwardian England, found expression in his happy marriage to an aristocratic Grosvenor, brought up amongst the grandeur of Moor Park. Thanks to that improbable match, this account of his life contains, at its heart, an enduring love story.

There were shortcomings and failures, of course. For one generally so modest, he never could quite let go of certain vanities. Like most essentially honest men, he could be disingenuous. He was loyal to a fault. His political judgement was sometimes wayward. He closed down on new literary ideas rather early in life. Although he did not worship success, he could be too tolerant of those who succeeded. He did not make it into the Cabinet. Spreading himself so widely, he never wrote the great novel of which he was (probably) capable. Grand filial loyalty has not prevented me from confronting his flaws and reverses with an historian’s unblinking eye.

I never knew him, but certain rather random material things have come down to me: a run of nine Morocco-bound books written by his sister, Anna, each with his bookplate, a stylised sunflower flanked by the initials ‘J’ and ‘B’; a gold ‘plaid pin’ brooch, comprising a finely wrought sunflower, encircled by the motto ‘Non inferiora secutus’, which means ‘not following inferior things’; a battered, japanned barrister’s wig box with ‘John Buchan Esqre.’ in faded gold letters on the front; a silver-gilt rose bowl, inscribed to ‘Their Excellencies the Governor General and the Lady Tweedsmuir from W. L. Mackenzie King Christmas 1938’; and a photograph of the Thirty-Second President of the United States, on which Franklin D. Roosevelt has written in his own hand, ‘For Lord Tweedsmuir with the regards of his sincere friend.’ The significance of this serendipitous collection of items can only be properly understood in the context of the story that has been unfolding for me, in fits and starts, all my life.

At home, his books were on the shelves and we heard family stories about him, although research for this book has inevitably been accompanied by the crump of exploding myths. The first real intimation I had of the extent of his fame occurred when my twin sister and I were about ten years old and went to play Bingo in our village Reading Room. We were fascinated by the way the caller gave an epithet to every number, such as ‘clickety-click, 66’, and astonished when he called out ‘all the steps, 39’. Until that moment, we had thought that a book by our grandfather was something essentially to do with our family. We had no idea that The Thirty-Nine Steps was famous enough to be a Bingo call.

At home, his books were on the shelves and we heard family stories about him, although research for this book has inevitably been accompanied by the crump of exploding myths. The first real intimation I had of the extent of his fame occurred when my twin sister and I were about ten years old and went to play Bingo in our village Reading Room. We were fascinated by the way the caller gave an epithet to every number, such as ‘clickety-click, 66’, and astonished when he called out ‘all the steps, 39’. Until that moment, we had thought that a book by our grandfather was something essentially to do with our family. We had no idea that The Thirty-Nine Steps was famous enough to be a Bingo call.

However, I have long been aware that much of this fame derived from the Hitchcock film. Furthermore, I have lost count of the times that people have said to me that they enjoyed John Buchan’s exhilarating adventure stories when young, but ‘of course’ they had not read him since. My response has been to urge them to try again, and also extend their reading beyond the thrillers, especially to his short stories and biographies, because they might be surprised by the underlying seriousness of purpose and by how intensely his writing resonates with universal, very grown-up concerns.

Returning to the fiction I had read when young and reading much that I had never broached before (the poetry, some of the biographies, and political thought), I discovered, as many have before me, that John Buchan was far more than a spinner of improbable but appealing yarns. He wrote some of the most lambent prose I have ever read, and he did so with an easy grace and elegance, a wit, an erudition, which resulted from lightly worn scholarship, a deep humanity and a life lived to the full. I discovered that he had much to say to me—not as a descendant, but as someone trying to navigate a responsible and cheerful course through life.

__________________________________

From Beyond the Thirty-Nine Steps: A Life of John Buchan, by Ursula Buchan, published by Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2019 by Ursula Buchan.