Meryl Streep didn’t quite nail the accent in A Cry in the Dark. No disrespect to her, ever: Australian accents are hard. And Lindy Chamberlain, the accused murderer played by Streep, has an unusually flat yet aggrieved quality to her voice. To replicate it precisely was not only challenging, it was risky. The filmmaker wanted viewers to empathize with one of Australia’s most vilified mothers.

You might remember the real-life case behind the film. In 1980, at Uluru, also known as Ayers Rock and the Red Heart of Australia, a two-month-old baby went missing from the local camping ground. Her parents, Lindy and Michael Chamberlain, claimed Azaria had been taken by a dingo. Trackers and police searched the flat, dusty area and patchy bushland but found nothing. Initially, the Chamberlains were believed. But a week after the disappearance, police found the baby’s jumpsuit, bloodied and torn, and the media—without evidence—suggested Lindy Chamberlain had murdered her daughter.

Lindy Chamberlain, who was young, attractive, energetic and working class, infuriated the media and public from the start: She looked the cameras in the eye, didn’t break down, and spoke in a resolute monotone.Lindy Chamberlain, who was young, attractive, energetic and working class, infuriated the media and public from the start: She looked the cameras in the eye, didn’t break down, and spoke in a resolute monotone. She snapped at reporters when they asked inappropriate questions. She wouldn’t play the role of anguished mother that was expected of her. And she refused to bow to baseless accusations.

Newspaper, TV and radio reports across the country incited the public to find Lindy Chamberlain’s demeanor suspicious, and suggested her claim of dingo aggressiveness was without basis (despite the fact that the local ranger had, for two years, been asking local authorities to initiate a cull of dingoes that had become threatening). They reported that she dressed her baby daughter in black, had indeed made her daughter a black dress. Ray Martin’s 1986 Australian 60 Minutes interview with Lindy Chamberlain was titled “Did You Kill Azaria?”

The Chamberlains were Seventh-day Adventists, a Protestant Christian denomination that believes in the imminent second coming of Christ. Michael Chamberlain was a pastor. This, too, inflamed much ill-informed rumor. The media reported that Azaria’s name meant “sacrifice in the wilderness” and that this was an Adventist practice. Neither is correct, and the name actually means “helped by God.”

To calm media and public hysteria, the coroner of the first inquest announced on live TV his finding that the Chamberlains were innocent, saying he wanted to put a stop to “the most malicious gossip ever witnessed in this country.” Unrepentant, the police continued their investigations, and the media held to its line that Lindy Chamberlain had cut the throat of her daughter.

After a second inquest and a trial, Lindy Chamberlain was sentenced to life imprisonment for murder, although no body or weapon had been found and no motive established. Protesters outside the courthouse carried signs that read “Don’t shoot animals for human lies”, “The dingo is innocent” and “Free her? No, hang her.” Heavily pregnant throughout the trial, she gave birth in Darwin Hospital and was then returned to jail. Meanwhile, “a dingo took my baby” became a punchline across the world, finding its way into scripts for Seinfeld and The Simpsons.

Three years after being incarcerated, police found, by happenstance, evidence that proved her innocence. She was released immediately with accompanying shame-faced government apology. In the next trial, expert witnesses claimed that marks on the baby’s jumpsuit were, in fact, consistent with marks made by dingo teeth.

Two decades after Lindy Chamberlain was pardoned, another mother came under the media’s attack. In 2007, three-year-old English girl Madeleine McCann went missing from a vacation resort in Portugal. In the beginning, people were sympathetic. Madeleine was blonde and pretty, and her parents (Gerry and Kate) were both doctors, articulate and untroubling. The McCanns knew to give the media what they needed to craft a good story. They hired a PR firm. Two weeks after their daughter went missing, they established a fund to raise money and awareness for their case. They met with politicians and celebrities.

Articles of the day claimed that Madeleine’s mother was too attractive, too thin, and that she was suspiciously composed. Like Lindy Chamberlain, Kate McCann was criticized for not crying enough.Their privilege and savviness didn’t help them for long though. The media, though a multi-armed beast, is consistent in being fickle. Outlets everywhere grew tired of the story, and annoyed at the parents for using the media as their personal tool. Newspaper and television reports became increasingly cruel, and much of their ire—as with the Chamberlain case—was directed at the mother. Articles of the day claimed that Madeleine’s mother was too attractive, too thin, and that she was suspiciously composed. Like Lindy Chamberlain, Kate McCann was criticized for not crying enough. When one report suggested this was because an abduction specialist had told her not to reward a kidnapper with a show of emotion, people suggested only a certain type of woman could follow that advice. The Sun (UK) newspaper ran the headline Kate McCann: Did you sedate Maddie?

Baseless claims were made. The Mercury (Australia) ran a story claiming that sniffer dogs had found “the scent of a corpse” on the McCanns’ Bible. On Twitter—only a year old when Madeleine disappeared—people suggested that if the McCanns were working-class, social services would have been called by the police upon learning that the parents were in a restaurant when their daughter was taken from her bed. Thirteen years after Madeleine’s disappearance, recent Twitter comments suggest the McCanns are part of a pedophile crime ring, are guilty because there are photos of them smiling, are making money from merchandise with their daughter’s image on it.

Throughout all this, the McCanns have continued to look for their daughter. There has not been a credible sighting of her since her disappearance.

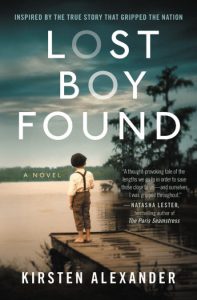

The real-life American case of Bobby Dunbar, which inspired my novel Lost Boy Found (Grand Central Publishing), is radically different—in life and fiction—and yet too much, sadly, is familiar. 4-year-old Bobby Dunbar went missing in Louisiana in 1912. Months later, the wealthy Dunbars thought they had found their missing son, despite claims by a woman named Julia Alexander that the child was in fact hers. The media took sides and cast aspersions on both the poorer woman, accusing her of neglect, indifference and chilliness, and the wealthier woman, casting her as weak-minded and foolish while somehow also being scheming.

In the novel, I hoped to explore ideas about family and identity. I hadn’t expected to encounter in research material the same type of inflammatory reporting that exists in modern times, and to learn how vicious the public could be to women they knew almost nothing about. Fiction allowed me to explore the mind of a reporter who would act in a compromised and partial way. And to look into the unique pain that comes with losing a child. Fiction also offered me the chance to invent a moment that I wish had happened in reality: to place the two mothers claiming the Louisiana boy in the same room and have them speak to each other.

In Lost Boy Found, as in life, people show their best selves when they try to help one another. I don’t want to give away too much about the actions in the novel, but in the real world Lindy Chamberlain spoke up on behalf of Kate McCann. In a magnanimous show of unity, Lindy Chamberlain called out the media for treating both mothers with contempt, sternly chiding reporters for their failure to learn, for once again inflaming rumors and spreading unfounded gossip. “How,” she asked in one interview, “can you apologize to me and do this again to someone else?”