The shiny raindrop fell from the sky, through the darkness, towards the shivering lights of the port below. Cold gusting north-westerlies drove the raindrop over the dried-up riverbed that divided the town lengthwise and the disused railway line that divided it diagonally. The four quadrants of the town were numbered clockwise; beyond that they had no name. No name the inhabitants remembered anyway. And if you met those same inhabitants a long way from home and asked them where they came from they were likely to maintain they couldn’t remember the name of the town either.

The raindrop went from shiny to grey as it penetrated the soot and poison that lay like a constant lid of mist over the town despite the fact that in recent years the factories had closed one after the other. Despite the fact that the unemployed could no longer afford to light their stoves. In spite of the capricious but stormy wind and the incessant rain that some claimed hadn’t started to fall until the Second World War had been ended by two atom bombs a quarter of a century ago. In other words, around the time Kenneth was installed as police commissioner. From his office on the top floor of police HQ Chief Commissioner Kenneth had then misruled the town with an iron fist for twenty-five years, irrespective of who the mayor was and what he was or wasn’t doing, or what the powers-that-be were saying or not saying over in Capitol, as the country’s second-largest and once most important industrial centre sank into a quagmire of corruption, bankruptcies, crime and chaos. Six months ago Chief Commissioner Kenneth had fallen from a chair in his summer house. Three weeks later, he was dead. The funeral had been paid for by the town – a council decision made long ago that Kenneth himself had incidentally engineered. After a funeral worthy of a dictator the council and mayor had brought in Duncan, a broad-browed bishop’s son and the head of Organised Crime in Capitol, as the new chief commissioner. And hope had been kindled amongst the city’s inhabitants. It had been a surprising appointment because Duncan didn’t come from the old school of politically pragmatic officers, but from the new generation of well educated police administrators who supported reforms, transparency, modernisation and the fight against corruption – which the majority of the town’s elected get-rich-quick politicians did not.

And the inhabitants’ hope that they now had an upright, honest and visionary chief commissioner who could drag the town up from the quagmire had been nourished by Duncan’s replacement of the old guard at the top with his own -hand-picked officers. Young, untarnished idealists who really wanted the town to become a better place to live.

The raindrop went from shiny to grey as it penetrated the soot and poison that lay like a constant lid of mist over the town despite the fact that in recent years the factories had closed one after the other. Despite the fact that the unemployed could no longer afford to light their stoves.The wind carried the raindrop over District 4 West and the town’s highest point, the radio tower on top of the studio where the lone, morally indignant voice of Walt Kite expressed the hope, leaving no ‘r’ unrolled, that they finally had a saviour. While Kenneth had been alive Kite had been the sole person with the courage to openly criticise the chief commissioner and accuse him of some of the crimes he had committed. This evening Kite reported that the town council would do what it could to rescind the powers that Kenneth had forced through making the police commissioner the real authority in town. Paradoxically this would mean that his successor, Duncan the good democrat, would struggle to drive through the reforms he, rightly, wanted. Kite also added that in the imminent mayoral elections it was ‘Tourtell, the sitting and therefore fattest mayor in the country, versus no one. Absolutely no one. For who can compete against the turtle, Tourtell, with his shell of folky joviality and unsullied morality, which all criticism bounces off?’

In District 4 East the raindrop passed over the Obelisk, a twenty-storey glass hotel and casino that stood up like an illuminated index finger from the brownish-black four-storey wretchedness that constituted the rest of the town. It was a contradiction to many that the less industry and more unemployment there was, the more popular it had become amongst the inhabitants to gamble away money they didn’t have at the town’s two casinos.

‘The town that stopped giving and started taking,’ Kite trilled over the radio waves. ‘First of all we abandoned industry, then the railway so that no one could get away. Then we started selling drugs to our citizens, supplying them from where they used to buy train tickets, so that we could rob them at our convenience. I would never have believed I would say I missed the profit-sucking masters of industry, but at least they worked in respectable trades. Unlike the three other businesses where people can still get rich: casinos, drugs and politics.’

In District 3 the rain-laden wind swept across police HQ, Inverness Casino and streets where the rain had driven most people indoors, although some still hurried around searching or escaping. Across the central station, where trains no longer arrived and departed but which was populated by ghosts and itinerants. The ghosts of those – and their successors – who had once built this town with self-belief, a work ethic, God and their technology. The itinerants at the twenty-four hour dope market for brew; a ticket to heaven and certain hell. In District 2 the wind whistled in the chimneys of the town’s two biggest, though recently closed, factories: Graven and Estex. They had both manufactured a metal alloy, but what it consisted of not even those who had operated the furnaces could say for sure, only that the Koreans had started making the same alloy cheaper. Perhaps it was the town’s climate that made the decay visible or perhaps it was imagination; perhaps it was just the certainty of bankruptcy and ruin that made the silent, dead factories stand there like what Kite called ‘capitalism’s plundered cathedrals in a town of drop-outs and disbelief’.

The rain drifted to the south-east, across streets of smashed street lamps where jackals on the lookout huddled against walls, sheltering from the sky’s endless precipitation while their prey hurried towards light and greater safety. In a recent interview Kite had asked Chief Commissioner Duncan why the risk of being robbed was six times higher here than in Capitol, and Duncan had answered that he was glad to finally get an easy question: it was because the unemployment rate was six times higher and the number of drug users ten times greater.

At the docks stood graffiti-covered containers and run-down freighters with captains who had met the port’s corrupt representatives in deserted spots and given them brown envelopes to ensure quicker entry permits and mooring slots, sums the shipping companies would log in their miscellaneous-expenses accounts swearing they would never undertake work that would lead them to this town again.

One of these ships was the MS Leningrad, a Soviet vessel losing so much rust from its hull in the rain it looked as if it was bleeding into the harbour.

The raindrop fell into a cone of light from a lamp on the roof of one two-storey timber building with a storeroom, an office and a closed boxing club, continued down between the wall and a rusting hulk and landed on a bull’s horn. It followed the horn down to the motorbike helmet it was joined to, ran off the helmet down the back of a leather jacket embroidered with norse riders in Gothic letters. And to the seat of a red Indian Chief motorbike and finally into the hub of its slowly revolving rear wheel where, as it was hurled out again, it ceased to be a drop and became part of the polluted water of the town, of everything.

Behind the red motorbike followed eleven others. They passed under one of the lamps on the wall of an unilluminated two-storey port building.

__________________________________

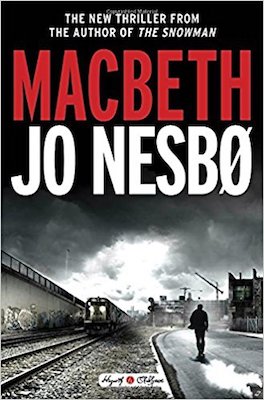

From Macbeth. Used with permission of Hogarth Shakespeare. Copyright © 2018 by Jo Nesbø