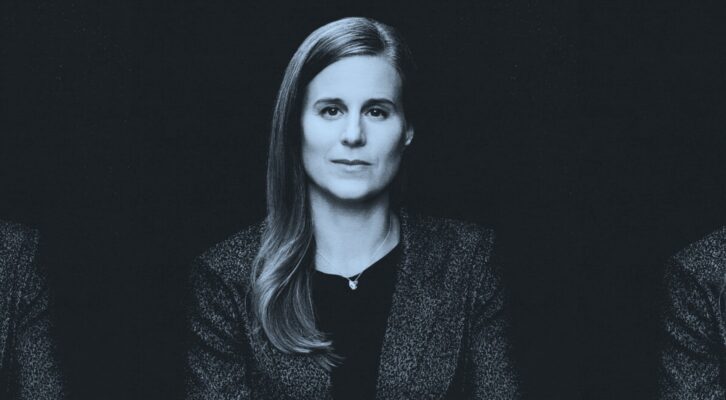

For writer Malcolm Mackay—chronicler of a fictional network of gangsters in a darkly atmospheric Glasgow—life on a small island in the North Atlantic Ocean keeps him grounded.

Born, bred and based in the town of Stornoway on the isle of Lewis, part of Scotland’s Outer Hebrides archipelago, Mackay relishes his existence of downright domesticity—living with his mom, and with his sister, brother-in-law and two nephews close by—as much as he enjoys mapping his intricate world of Glaswegian gangsterland. “I did always read a lot of crime fiction,” says Mackay via Skype. “And when it came to writing something like that myself, I was drawn to the unfamiliar. I think a lot of crime fiction is about exploring things you don’t know. For me, it was the lure of the completely unfamiliar: the urban gangster.” He did, though, cling to the known in one regard: “Being Scottish made me want to set my books in Scotland,” he says. “So there’s some familiarity there. Glasgow is a place that I’ve been to, so it wasn’t completely alien to me. And if you’re going to set these stories in a Scottish city, in terms of the personality of the place, I think that Glasgow is a better fit than Edinburgh or anywhere else. I think there’s a toughness to Glasgow that Glasgow’s sort of oddly proud of and doesn’t hide away from. It’s a good setting for these kinds of characters, ones who are sort of openly and demonstrably tough and nasty people. I put them in a city that has the strength of personality to contain them, that has the kind of history that they can slot into more easily.”

Mackay’s been staking his literary claim in that city on the Clyde since his Glasgow Trilogy—detailing the wayward and gory travails of hitman Calum MacLean and his cronies—was first published in the UK in 2013. (The middle book, How a Gunman Says Goodbye, won the prestigious Deanston Scottish Crime Book of the Year at the Bloody Scotland festival that same year). The trilogy was published in America in 2015, and, since then, two more related thrillers have followed in quick succession, including Every Night I Dream of Hell, out this month from Mulholland. “I had been writing short stories and all sorts of rubbish since my mid-twenties,” explains Mackay, who was homeschooled from the age of 14, when he was sidelined by chronic fatigue syndrome. “But I wrote the first book of the trilogy in early 2011. I’d had ideas for a story built around an isolated young man, someone hiding himself from the world, and I knew I wanted to write crime fiction. The two came together in the trilogy.”

In one of those remarkable slush-pile stories, Mackay got a publishing deal through agent Peter Robinson at Rogers, Coleridge & White in London. “When I’d written the first book, I emailed Peter Robinson a sample, not knowing anyone in the publishing industry and assuming I would get nowhere. Within a couple of weeks, he asked to see the complete manuscript. He became my agent and within a couple of months I had a publisher. I was very lucky, getting through the slush pile of pretty much the first agent I emailed, and getting a publisher so quickly. I remember it was September 8th, 2011, that the deal was agreed. It was one week after my 30th birthday which was a hell of a present.”

Aside from his detailed depiction of a corrosive and sprawling system of organized criminals perpetually enacting a twisted form of multi-player chess, Mackay’s characters, deviant and bad as they may be, are always thoroughly engaging. Even when his books feature a particular protagonist, Mackay gives generous time to the peripheral characters, many of whom reappear in his other novels. It’s not unusual for minor characters from earlier books to morph into a major character later on, as happens with Every Night’s Nate Colgan, a classic Mackay creation: a heavy-for-hire who’s not entirely amoral, grappling from time to time with the direction and requirements of the career he’s chosen.

“In the first books, with Calum,” Mackay explains, “I wanted to have someone who’d walked into a job that he felt was an uncomfortable fit. He’d have this growing awareness as he gets deeper and deeper into it that he’s in a place he doesn’t really want to be, and, finally, wants to get out of. Nate had been in some of the early books; he was a character that I’d always wanted to do more with. I had him in the background, this thuggish tough guy that people use as a threat against others, but I liked the idea of turning him into something a bit more broad, a bit more human. He’s not doing the things that Calum did in terms of killing people, so Nate finds it easier to justify his work: he’s actually more comfortable with that gangster-world until it starts to infringe on the other things he cares about. Calum didn’t have a daughter, Nate does, and it was interesting trying to create a character who’s not trying to escape the world he’s walked into. But he is trying to reshape it to fit his ideals, and he’s tough enough to think he can do that. The funny thing about doing it from Nate’s point of view—and this is the first book I’ve done from a first-person perspective—is that it carries you off into places you didn’t expect. By the time I reached the end of the first draft of this book, Nate was sort of less of a reactionary than I wanted him to be: he was different to what I expected him to be because he went through this whole thought process about how he does his job. He becomes much more accepting of things he can’t change.”

Every Night I Dream of Hell brings back another minor character from an earlier book, one Zara Cope, girlfriend of the doomed Lewis Winter in The Necessary Death of Lewis Winter. (Mackay’s titles tend to rival those of fellow crime-fiction scribe Adrian McKinty when it comes word count). In Every Night, she’s also Nate’s former girlfriend, the mother of his daughter, and when she rolls into town after a long absence, Nate knows there’s trouble afoot—he just doesn’t know how much. Zara’s return stirs a nasty nest of human-shaped vipers, giving Mackay another sharp, knowing opportunity to expose the ins and outs of his Glasgow mob, one rife with debt-collecting, money-laundering and other, far more unsavory activities.

But Mackay is also highly adept at rendering the gangsters’ more quotidian business-related activities—the politics, the interpersonal dynamics, the mind games, the Machiavellian leadership machinations—with clarity and insight. The baddies hold meetings, make plans and aggressively defend their turf with a take-no-prisoners attitude, and Mackay’s lean, staccato prose is the perfect medium, rendering his characters and their actions in stark relief against the just-as-mean Glasgow streets.

“When I wrote the very first book, Zara, in my mind, was always going to be this unpleasant background character,” Mackay says of this other minor player who clearly got under his skin. “But characters definitely surprise you: I had more fun writing her than I did a lot of my other characters, so I wanted to do more with her. The thing about Zara is that when I used her in the first book, she was just reacting to other people’s doings; she was sort of dragged along with the story. But with this book, I wanted her to be one step ahead of the game, reflect the fact that she’s smart and she’s cunning and she’s good at knowing what she’s doing. From Nate’s perspective, Zara’s just this irritation—he’s not recognizing that she’s actually pulling her own strings. And that was fun, to write it from the point of view of someone who doesn’t necessarily recognize just how sharp she is, that she can stand up to him. I liked the idea of having somebody who can tell Nate that he’s a bad guy. The thing about Nate is that he’s surrounded in his world by other baddies; they’re all afraid of him but they’re all doing terrible things as well so nobody’s going to tell him that he’s a scumbag. It takes somebody like Zara who understands not just his job, but understands how to bring him down a peg or two, to make him understand what he is.”

The ongoing intrigue underlying Every Night, enhanced by the perpetual suspense-filled interactions—conversations, fights, backstabbings, plottings—emphasize the relentless tension inherent in gangster living. No one can ever rest easy; a new threat to someone’s power might pop up at anytime, from anywhere, a tangible impression that imbues all of Mackay’s thrillers with their electric readability. “When I first started making notes to write this book,” says Mackay, “I realized it’s all about survival strategy. Crime boss Peter Jamieson is in prison, and when a leader is in prison the survival strategy isn’t just about outsiders attacking your turf because people think you’re weak, it can also be people within your own organization. So there’s that complete lack of trust, even with those that you’re working with, people that you’re supposed to be able to rely on. I wanted to explore that, to fiddle around with that. And that sensation does go back to Calum’s trilogy, the idea that at every single point in the story you’re one slip-up away from someone betraying you. Even if they don’t intend to at the start of the day, by the end of that day someone may very well throw you under the bus. You’re working and existing in the world in which you can’t trust anybody.”

While Mackay appreciates the scope and variety of contemporary crime fiction—which appears to be having a particularly burnished golden age in Scotland with authors ranging from Val McDermid, Doug Johnstone, Lin Anderson and Christopher Brookmyre to Denise Mina, Peter May and Ian Rankin—his early influences were trans-Atlantic. “The crime fiction that influenced me most, that started me writing properly at first, was American, hardboiled and noir: Jim Thompson, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler,” he says. “And then seeing how William McIlvanney brought in intelligence and the social aspect to crime fiction here, right here in Scotland. I don’t know what it is about us Scots that we seem to find murder and crime and death as being a sort of jumping off point to write about a whole lot of other things, but I do think that the thing about crime fiction is that that whatever subject you want to have at the heart of your book, you can work within this genre. There’s almost nothing I can imagine that would be outside the range of crime fiction. For me—and I would assume for other writers as well—one of the things with crime fiction is that it’s such a broad church: it allows you to touch on any variety of subjects that you might want to explore as a writer. You can set it anywhere,” he continues, warming to the topic.

“You can make it rural or urban, political or social, whatever route you want to go down… I mean, there are some obvious parallels between gangsterism and modern politics right now. A lot of us feel a bit like we’re living in a crime novel at the moment: there are going to be a lot of references in books that are being written now to things that are happening on both sides of the Atlantic. And whether you’re writing about gangsters or writing about politics, both are so much about controlling the message, controlling it just long enough to get into power. And then once you get into power, you can use that to silence your opponents. Seeing what’s happening around us, alarming as it is, there are obvious parallels, and I think that’s going to end up in a lot of fiction.”

So far, Mackay’s sticking to his Glasgow setting, a place he’s still exploring as a writer. “My levels of research are nothing to be terribly proud of,” acknowledges the writer, who visits the city a few times a year, “just for buying books and stuff.” His island home, he says, has no pull for him as a writer. “Stornoway is so familiar that it just isn’t a fascinating setting to me. It’s a very small town. In terms of crime rate, I think there’s one murder every 50 or 60 years, something like that, so it’s not exactly a capital of death. It’s a peaceful little harbor town, quiet and cold and wet, part of an empty island with hills and beaches and scattered villages. It’s a world away from the rough gangsters of Glasgow. I’ve been here all my life, and it’s easy to know all of it. There’s nothing for me to learn, particularly, by writing about it.”

Still, if his island home and family keep Mackay grounded—“you want to talk about the challenge of being in charge of controlling the message, a nine-year-old and a five-year-old would be the ones to talk to about it”—they clearly allow his imagination to run wild while responding to Glasgow’s Siren song. “It’s the same in terms of the way that I’m attracted to characters that are totally different from me,” notes Mackay. “I mean if I tried to behave like some of my characters, I’d just get my head kicked in. Having characters that are totally different from me and having a setting that’s totally different as well, it’s a learning experience. I think that’s what makes writing a little more fun.”