The diamond world was stunned when De Beers, the storied diamond miner, announced this month it was ditching its lab-grown diamond business. De Beers had been selling lab-grown gems online through its Lightbox brand for six years, at prices its competitors found hard to beat. But the lab-grown diamond price was crashing, and De Beers will now focus its $94 million Oregon diamond factory away from gemstone production and onto something much more exciting: diamonds for targeted industrial uses.

Among these new and often secret uses is the place of diamonds in the race to develop a quantum computer—the mind-boggling doomsday machine that China and the United States are desperate to get to first. De Beers diamond-technology experts have put the company in the forefront of this race, with their ability to manipulate tiny diamonds at the atomic level. Characteristics such as “vacancies”—missing atoms—allow such stones to perform a crucial function for quantum machines, which will complete in minutes calculations that today’s fastest supercomputers would take years to finish. The plot for my new novel, The Lucifer Cut, revolves around these developments. But first—how did diamonds get where they are now?

I started writing about diamonds in 1991, when a discovery in the Canadian Arctic sparked a winter staking rush. Loaded with posts, planes flew out into the frigid wastes. At isolated tent camps, diamond geologists and staking crews shifted the posts into helicopters and clattered off to distant coordinates, often just flinging the posts out into the snow when they got there and inking another claim onto the staking map. Tens of millions of dollars in speculators’ money poured into that rush, all of it riding the same belief—that diamonds were valuable and hard to find. In other words, rare.

Rarity is the basement attribute that supports the diamond industry. Without that concept, the whole idea of a jewel is under threat. That threat became real when a virus invaded the sparkling domain of diamonds, destroying the very idea of rarity. The virus was lab-grown diamonds.

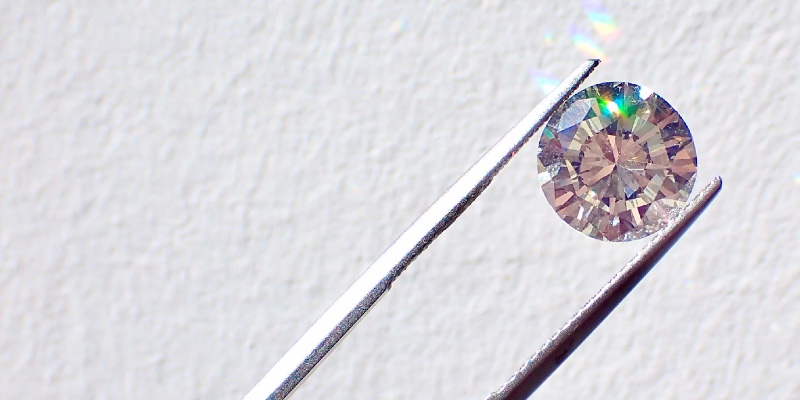

Diamonds depend for value on distinctions of rarity. D color costs more than F because there aren’t as many Ds; a two-carat stone is rarer than a one, so you pay more per carat. Absurdly, lab-grown diamonds shadow this pricing system, even though the supply of lab-grown, in any practical sense, is infinite. There is no such thing as rarity. Diamond growers can make as many stones as they like, and even advance a stone from one category to another basically by leaving it in the oven a little longer. By that I mean that industrial processes involving heat and pressure, not the casino of natural formation, determine what a stone will look like.

The only value of a lab-grown diamond is that it looks like something it is not. How do you even sell such a stone? In an industry whose mother ship is the idea of eternal love, you don’t want the whole retail pitch to just be that it’s cheaper than the real thing. So the makers of lab-grown found another story: namely, that that the stones are more ethical and greener than natural diamonds.

It was a ridiculous claim. The Federal Trade Commission ordered lab-grown manufacturers to drop it five years ago. Yet somehow the belief that lab-grown have a moral edge has stuck. The truth is that most lab-grown diamonds come from factories in China and India that rely on huge amounts of electric power. That power comes from coal-fired generating plants. So much for the eco edge.

The other idea, that lab-grown are more ethical, is laughable. It’s a hangover from the blood-diamonds scandal, which exposed the trade in conflict diamonds. But anybody who thinks a diamond made in a Chinese or Indian factory is more ethically sourced than a mined one hasn’t been following the relentless campaigns of persecution against ethnic and religious minorities by governments in New Delhi and Beijing.

Buyers flocked to lab-grown anyway, pushing the category’s share of the global diamond market last year to more than twenty percent. Since the supply is essentially limitless, manufacturers responded to the boom by producing even more. Choked by oversupply, the wholesale price collapsed, and as sure as night follows day, the retail price began to follow it. Since the price of natural rough diamonds had also taken a haircut, this meant the whole industry—natural and lab-grown—was caught up in a price retreat that looked like a rout. Into this dangerous moment stepped the only force in diamonds that could stop it—De Beers.

De Beers invented the modern diamond business. For decades they ran it like a private fief. They are still a powerful force—the pre-eminent natural diamond company and a successful lab-grown maker too. This made De Beers the only power that could calm the seething waters of the lab-grown diamond price, and in May they tried. They slashed the price of their standard range of lab-grown goods from $800 a carat to $500. How did that work out? Not great, I guess, since a month later they threw in the towel and got of lab-grown altogether.

When lab-grown diamonds appeared, I thought they would turn out to be the virus that ate itself—a commodity whose basic worthlessness would ultimately push down prices until the enterprise went bust. I didn’t see the other threat, the more insidious one, which was how good they would get. It was that penny finally dropping—that fakes might actually get good enough to beat the tests designed to catch them—that convinced me to set my new thriller, The Lucifer Cut, in that world.

Here’s an example. One recent fake—a six-carat white—appeared in Tel Aviv. The fakers had found a natural diamond just like it on an online data base. Their fake even had flaws positioned where the natural stone’s flaws were. The online stone was identified, as any large diamond would be, by a certificate whose number was lasered on the stone. No problem. The fakers lasered the number on theirs. This fake was caught when a trader brought it to a lab, which detected minute differences between the natural and the fake, and ran some tests. But in an intensely secretive art whose sorcerers can reposition atoms, one day the tests will fail to catch it. From that moment the diamond business is finished. The Lucifer Cut dives into this dark realm as Treasury agent Alex Turner and his lover, the millionaire Russian diamond thief known as Slav Lily, pursue an elusive genius who can make any diamond—including one that could give its owner the power to rule the world. In The Lucifer Cut, nothing is stranger than fiction!

***