What happens when a professional from the Tamil film industry and a California native with a background in math education get together to form a publishing company? Blaft Publications, founded in 2007, is unorthodox even as indie presses go. In their hometown of Chennai, India, they’re especially left-field. Over the past decade they’ve filled a distinct niche with their off-beat book list (everything from Indian folklore to graphic novels to weird fiction), strong design aesthetic, and the fact that they publish some of the only available English translations of pulp crime fiction from both India and Pakistan, bringing regional writing to an English-reading audience. At their most recent book launch, a welcoming open-air event at an indie bookstore with intrigued passers-by stopping to watch, co-founder Rakesh Khanna and translator Nirmal Rajagopalan talked about and read from two new releases: Math Problems with Dinosaurs (which is what its title promises—a math book featuring dinosaurs) and The Aayakudi Murders, Blaft’s latest offering in translated Tamil crime fiction. Rajagopalan’s reading—featuring thunderstorms, serial murder, and supernatural intrigue—was a compelling teaser for the wild tale originally written in Tamil by pulp veteran Indra Soundar Rajan. Blaft has more releases planned for the rest of 2019, with the year being marked out as a comeback of sorts after a brief lull. As a longtime fan, I was lucky to sit down with co-founders Rakesh Khanna and Rashmi Ruth Devadasan and talk Blaft, Tamil pulp, and what it’s been like bringing an under the radar genre of crime writing out into the mainstream.

It’s so cool that the two of you ended up founding Blaft despite not having traditional literary backgrounds. Where did the initial spark come from, and how did your interests lead to Blaft becoming what it is today?

Back in 2006, when we were living in Indira Nagar [a neighborhood of Chennai], Rakesh noticed that several of local tea-stalls (which usually double as newsstands) had these pocket novels hanging on a clothesline. He couldn’t read Tamil but could sound out the script, and most of the novels turned out to have English titles like “Super Bumper Horror Detective Novel” or “Tiger Police Diary.” The covers were these brilliant Photoshop collages of heavy metal album covers, horror and video game screengrabs, and Kollywood movie stills. They sold for 10 rupees (then about 25¢), and he was madly curious about the stories inside them.

Back in 2006, when we were living in Indira Nagar [a neighborhood of Chennai], Rakesh noticed that several of local tea-stalls (which usually double as newsstands) had these pocket novels hanging on a clothesline. He couldn’t read Tamil but could sound out the script, and most of the novels turned out to have English titles like “Super Bumper Horror Detective Novel” or “Tiger Police Diary.” The covers were these brilliant Photoshop collages of heavy metal album covers, horror and video game screengrabs, and Kollywood movie stills. They sold for 10 rupees (then about 25¢), and he was madly curious about the stories inside them.

Around the same time, Rashmi was planning on setting up a design firm and releasing a couple of comics. She likes using made-up words—“Blaft” initially meant something like “weird and otherworldly”, and then it ended up being the name of the company! She got a designer friend of ours, Raghuram A, to come up with our spaceman logo. In the meantime, Rakesh met Pritham Chakravarthy, who had grown up reading Tamil pulp novels, and told her about our interest in Tamil pulp fiction. She gave him synopses of the pocket novels that had intrigued him so much, and pretty soon we were contacting the authors for rights. We launched our first anthology of Tamil pulp fiction in 2008, along with an English translation of an experimental Tamil novel and an art book.

Speaking of art, pretty much each Blaft book is like an art object—the design and covers are so striking! Are there artists you’ve worked with repeatedly to establish this distinctive visual aesthetic?

The first Tamil Pulp Fiction covers were collaborations between Malavika PC and the fantastic Tamil pulp artist Shyam. Malavika also did a couple of other excellent covers for us, including Insects Are Just Like You and Me Except Some of Them Have Wings, a short story collection by weird fiction writer Kuzhali Manickavel and Ki. Rajanarayanan’s collection of Tamil folk tales, Where Are You Going, You Monkeys? Shyam’s art is the most recognizable in Tamil publishing – his work has appeared in all the popular Tamil magazines and even magazines from other South Indian states. He also collaborated with Rashmi on Kumari Loves a Monster, our picture book of girls in love with monsters.

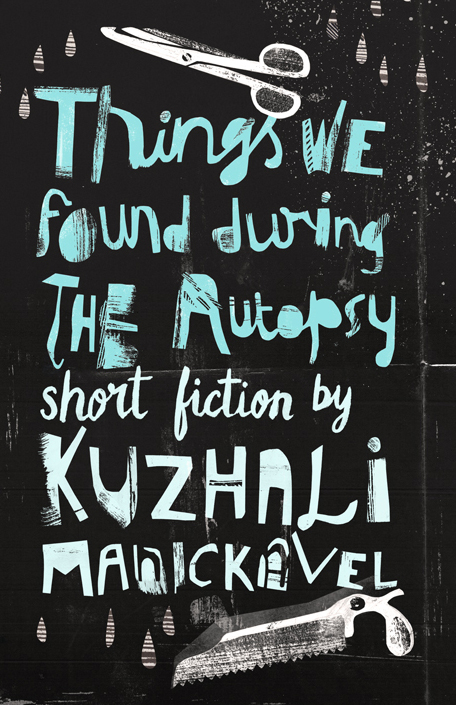

Another cover designer we’ve worked with is Prabha Mallya, a badass artist/designer who’s worked extensively with the indie publishing house Studio Kokaachi in particular. She drew the image for the cover of volume 2 of our comics journal, The Obliterary Journal—an aunty with a cut of meat for a face—and also did the cover for Kuzhali Manickavel’s second short story collection, Things We Found During the Autopsy.

I’m no expert, but it seems like Tamil pulp fiction isn’t terribly well-documented and hasn’t garnered that much scholarly attention even though it’s read by large numbers of working-class Tamilians. Could you tell me more about the process of selecting the pulp titles you’ve published and how reception has been from the reading public?

When we released the first Tamil Pulp Fiction anthology, there was pretty much zilch–absolutely zero mention of Indian language pulp fiction in any English publication, anywhere; not for Tamil, Hindi, Marathi, Telugu, or Kannada. The more literary authors were discussed, of course, and those who wrote in English; but I have never found an article from before 2008 that mentions any of the genre fiction, the crime or horror or romance novels. Which is kind of astounding, because we’re talking about tens of thousands of titles in dozens of languages, mass-produced for almost a century, and read by hundreds of millions of people.

When we released the first Tamil Pulp Fiction anthology, there was pretty much zilch–absolutely zero mention of Indian language pulp fiction in any English publication, anywhere; not for Tamil, Hindi, Marathi, Telugu, or Kannada. The more literary authors were discussed, of course, and those who wrote in English; but I have never found an article from before 2008 that mentions any of the genre fiction, the crime or horror or romance novels. Which is kind of astounding, because we’re talking about tens of thousands of titles in dozens of languages, mass-produced for almost a century, and read by hundreds of millions of people.

Since our first book came out, there’s been a bit more attention paid to Indian pulp – some academic papers, a collection of translated Bengali pulp stories. We even got to speak to a class at the University of Berkeley, California, where Blaft’s pulp anthology was part of the course curriculum. But at the same time, readership in Indian languages seems to be falling, with the older generation switching to TV and the younger generation reading mostly in English. So it still seems to be a niche interest.

When we first started Blaft we thought we’d have an easier time selling in the US (where our books are distributed by Small Press Distribution) and a harder time selling in India, but we had it backwards! There are lots of Indians who are eager to read Indian language fiction but are more comfortable reading in English, and our pulp and folklore translations have done well with that crowd.

Aside from Tamil crime fiction, Blaft also publishes Pakistani crime fiction, primarily the work of the Urdu writer Ibne Safi. What led Blaft to Pakistani crime fiction, and how’s it different from your other specialty, Tamil pulp fiction?

After our Tamil pulp anthologies got a good response, we wanted to bring out translations of other Indian language pulp, and tried getting rights to translate a couple of bestselling crime writers from Hindi, Telugu, and Konkani. Unfortunately, there are a lot of issues with plagiarism—there’s a phenomenon of “transplant fiction”, where an author takes a Western crime writer, translates the English line-for-line into Hindi, and changes Western references to Indian ones (for instance, Chicago becomes Chandigarh, and hamburgers become samosas), then publishes the book under his own name without crediting the original. Some of these are done quite artfully, and if you haven’t read the originals you wouldn’t be able to tell that they’re plagiarized. So as a publisher you have to be careful.

On the other hand, there’s Ibne Safi, who was undoubtedly, absolutely original. He was the bestselling crime/thriller writer in Pakistan from the 50s through the 70s, and he had a big following in India as well. His work is a little harder to get for an English reader than most Tamil crime. The genre he invented has less in common with Western crime writing and more in common with dastangoi, an oral storytelling form that was popular in late 19th-century opium dens and has roots in Persian epic poetry. Safi’s stories have all the familiar elements from vintage Western pulp—smoky nightclubs, chloroform, gangsters in trench coats, femmes fatales, etc.—but the stories are trippy. The plots are held together by dream logic and the dialog is absurdist. One main character has a pet goat that wears a tie and hat, and he’s constantly reading poetry to it.

On the other hand, there’s Ibne Safi, who was undoubtedly, absolutely original. He was the bestselling crime/thriller writer in Pakistan from the 50s through the 70s, and he had a big following in India as well. His work is a little harder to get for an English reader than most Tamil crime. The genre he invented has less in common with Western crime writing and more in common with dastangoi, an oral storytelling form that was popular in late 19th-century opium dens and has roots in Persian epic poetry. Safi’s stories have all the familiar elements from vintage Western pulp—smoky nightclubs, chloroform, gangsters in trench coats, femmes fatales, etc.—but the stories are trippy. The plots are held together by dream logic and the dialog is absurdist. One main character has a pet goat that wears a tie and hat, and he’s constantly reading poetry to it.

We published four books from Safi’s “Jasoosi Duniya” (Spy World) series, translated into English by Urdu literary giant Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. They haven’t done as well as the Tamil Pulp Fiction books, but we enjoy them. A whole generation of Pakistanis grew up reading these novels, so we think they’re important for anyone who wants to understand the Pakistani mindset. We even had a blurb from A.Q. Khan, the father of the Pakistani nuclear bomb and a huge Ibne Safi fan! Rakesh thought that would’ve guaranteed a few dozen sales to the US Department of Defense or Intelligence or something, but that didn’t seem to happen. [laughs]

And finally, for anyone who’s intrigued and wants to explore Tamil crime fiction further, which authors would you recommend?

And finally, for anyone who’s intrigued and wants to explore Tamil crime fiction further, which authors would you recommend?

When it came to putting together our Tamil pulp anthologies, we wanted to present a cross-section of the most popular authors and subgenres. The first is a little heavier on crime and detective fiction, so it’s a good place to start for anyone who’s interested in Tamil crime fiction. A few of the biggest names include Subha, Pattukkottai Prabakar, and Rajesh Kumar. (Subha are actually a writing duo, Suresh & Balakrishnan. We interviewed them some years ago for the Blaft YouTube channel.) Indra Soundar Rajan, who wrote The Aayakudi Murders, writes straight crime fiction once in a while, but most of his stories have religious or supernatural elements – things like reincarnation or hundred-year-old cobras with magical gems in their skulls.

In terms of their styles, Subha and Pattukkottai Prabakar are similar. They’ve both written series with mixed-gender detective duos—unmarried couples who track down bad guys while flirting, bickering, and trying to outdo each other. Subha’s detectives are Narendran and Vaijayanthi from Eagle’s Eye Detective Agency, while Prabakar’s are Bharat and Susheela from Moonlight Agency. Subha and Prabhakar have even collaborated on a few “double-dates” featuring both pairs of detectives.

Rajesh Kumar is a little different. He claims to be the most prolific living fiction writer in the world—he’s been publishing around 3 short novels a month since 1968. When you’re reading his books, you can often tell that he’s making it all up as he goes along, but that’s part of the fun. You get to ride along watching him figure out how to bring everything to a conclusion.