Death of a Mystery Writer

Six decades ago, on March 7, 1962, the body of fifty-five-year-old Milton Morris Propper was discovered slumped over in his automobile outside his apartment residence at 1841 West Tioga Street in the Nicetown-Tioga section of northern Philadelphia. Authorities concluded that the dead man had expired in his car three days earlier from “acute barbiturate poisoning”—or, in other words, a fatal overdose of sleeping pills, taken deliberately. This is the sort of death scenario that Golden Age mystery writers are known to have concocted, although in those fictional cases the dead man invariably turns out to have been a victim not of suicide but of cannily crafted foul play which duped hopelessly credulous cops (though not, of course, the brilliant amateur sleuth). Ironically, as the brief national newspaper obituaries of Milton Propper at the time noted, the deceased himself once had been, during the years from 1929 to 1943, the heyday of Golden Age detective fiction, a published mystery writer of no small repute.

By the late 1950s, however, Milton Propper had ended up destitute and forgotten. A 5’4”, brown-haired, grey-eyed man of 125 pounds (according to his 1940 draft registration card) who was born on August 6, 1906, the washed-up, former author, now in his fifties, had drifted alone into a one-room apartment in Nicetown, a crime-plagued, redlined, lower-income neighborhood undergoing heavy black in-migration and concurrent “white flight.” Recently the populace of Nicetown had been isolated and atomized by the construction of the so-called Roosevelt Extension, an elevated highway that was designed, by connecting Roosevelt Boulevard and the Schuylkill Expressway, to facilitate commuter traffic between downtown Philadelphia and its suburbs. “The highway will benefit all the citizens,” patronizingly pronounced a white Philadelphia councilman. “Unfortunately, some must be hurt. In modernizing the city that is usually the case.” (See Elizabeth Greenspan’s June 2019 article “Nicetown” in placesjournal.org.)

Hurt they were in Nicetown. A couple of years before Milton Propper’s March 1962 suicide, a forty-six-year-old “Nicetown Divorcee,” as the headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer saw fit to put it, was robbed of nineteen dollars from her purse and sexually assaulted upon returning home from a shopping trip to her apartment on North 21st Street. Before raping the woman, her assailant ordered her at gunpoint into the bedroom and tied her hands behind her back with shreds of her own ripped dress, afterward leaving her bound in the closet. In a 2019 article on crime in the Philadelphia Citizen (“Of Course, It Was Nicetown”), Charles D. Ellison observed wearily: “Nicetown may be one of the more oxymoronic designations for a large city neighborhood brutally tucked into an armpit corner of north Philadelphia.” The next year, in an episode of his driving tour program on YouTube, TOON215 dubbed Nicetown-Tioga Philadelphia’s #1 Dangerous Hood. At the forty-five minute mark in the video, he cruises down North Nineteenth Street, past the vacant lot at 1841 West Tioga, where Milton Propper died.

After World War Two future Nicetown denizen Milton Propper left his day job as an administrative assistant with the United States Civil Service Commission, having resolved to revive his failing mystery writing career. Later, after this effort proved unavailing, he found himself unable to recover his government position, having been arrested in the interim for committing what was then condemningly termed a “homosexual offense.” The censorious American Fifties, then in the lurid Technicolor thrall of its Red and Lavender Scares, did not look kindly on government bureaucrats with queer tendencies, either political or sexual.

Milton Propper’s late parents had been well-off Philadelphians, immigrant Jews from the Austro-Hungarian Empire who achieved worldly success in the City of Brotherly Love. His father, Sigmund Jacob Propper, had been a partner, along with his uncles Morris (Moritz) and Samuel, in Propper Brothers, a furniture store overlooking the Schuylkill River in the neighborhood of Manayunk. Founded by the enterprising Proppers in 1888, the concern, still family owned, closed a dozen years ago, but it lives on today in another form as Propper View Apartments. However, when Milton’s father Sigmund and his mother Helen passed away within a few weeks of each other in 1944, they left their younger son with but a small cash inheritance, which he soon depleted. As his personal problems accumulated in the Fifties, Milton became estranged from his remaining family members, including his younger married sister Madelyn, with whom he had once been very close.

Today the apartment building where Milton Propper lived out his last years is gone. In its place is simply an anonymous vacant lot, which seems sadly fitting. Standing to the side of this empty, grassy space is Our Lady of Hope Catholic Church (known at the time of Milton Propper’s solitary, hopeless death in his car as Our Lady of the Holy Souls), an imposing gray Romanesque Revival structure which has recently been reopened as a youth recreation center after having been closed for years. How different from the site of Milton Propper’s end was the gray fieldstone, colonial-style house located at 546 Walnut Lane in the Roxborough neighborhood of northwestern Philadelphia, just a mile away from Propper Brothers, where from his birth in 1906 into the 1930s Milton had lived with his father and mother (who were second cousins), his sister Madelyn and his slightly older brother Walter.

Across the street resided Julius Propper, a prominent doctor and a cousin of Milton’s parents, along with Julius’ wife Gizelle (Samuel’s only sister) and their two sons, Mortimer and Leonard, the latter of whom would become an assistant district attorney and municipal court judge. Two miles away in Germantown there lived Helen Propper’s sister Antonia, her husband Isadore Schachtel, a dry goods merchant, and their son Walter, a Harvard degreed lawyer a couple of years younger than Milton, whom the latter would appoint the executor of his estate (consisting mostly of copyrights to his detective novels). At age ninety-one, as a new century dawned, Milton’s long-lived and prosperous Cousin Walter published a book of professional reminiscences, Memoirs of a Lucky Lawyer.

Milton’s mother grew up in Cleveland, Ohio in a family of nine children, eight of whom married, so he had numerous kinfolk on her side of the family. Through Helen’s myriad relations Milton became familiar with the Midwestern cities which appear in his detective novels, which are set primarily in Philadelphia. Other relatives with whom he was close during his youth included Helen’s youngest sister Blanche (Blanca) and her hardware merchant husband Merrill Whitelaw, a son of Akron, Ohio rags-to-riches immigrant wholesale liquor dealer Jacob P. Whitelaw (formerly Weislovitz); and her youngest brother Harry (Heinrich), a prominent Cleveland, Ohio nightclub “impresario” who claimed to have discovered Guy Lombardo and Martha Raye, advising the latter entertainer: “The only thing you can do is to use your mouth.”

In the 1930s Harry Propper, described by contemporaries as a jolly glad-hander and “very polished gentleman,” acted as managing director of Cleveland’s posh $200,000 Mayfair Casino, a restaurant and revue theater with back room gambling. (Future Hollywood mogul Lew Wasserman, then in his early twenties, handled publicity.) In reality happy Harry served as a front man for the casino’s silent partners, a coterie of mobsters including future Las Vegas developer Morris “Moe” Dalich. Critic Francis Nevins scoffed at Milton’s depiction of organized crime in his novels (see more on his critique of the author below), derisively pronouncing: “The fastidiously elitist Propper can’t make an underworld setting plausible for a microsecond.” Yet in his Uncle Harry the author had a relative who possessed considerable personal knowledge of the subject.

As a youth Milton Propper was a bookish, heavyset lad with an apparent squint (judging from photographs), who may have been something of a sheltered “mama’s boy.” Yet during the Jazz Age, when he was in his Twenties, Milton, anticipating the burgeoning fitness movement among gay men, took up physical culture, lost his excess weight and developed a trim, attractive figure. Indeed, as a young man Milton could have served as a “before-and-after” model in male fitness magazines from the period. Markedly contrasting with his portly senior year photo at Penn, taken in 1926 when he was nineteen, his 1930 publicity photo, taken when he was twenty-three, reveals a full-lipped, darkly handsome young man with an intense, even smoldering, gaze—one who, in terms of his visual macho sex appeal, could have passed muster as an idealized writer of hard-boiled mysteries.

Back in his earlier, happier years Milton received his primary education at Nazareth Hall, a boarding school north of Philadelphia originally founded by Moravians in the eighteenth century, where he compiled an outstanding academic record, wrote “innumerable serials, skits and dramatizations” and graduated at age fifteen in 1922. He then enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, where he became a zealous member of the historically Jewish fraternity Sigma Lambda Pi, to whom he would dedicate his fourth detective novel, The Student Fraternity Murder (1934), and graduated with honors and a B. S. degree at age nineteen in 1926. Despite his adversities later in life, Milton remained a loyal alumnus, serving as an officer in Nazareth Hall and Penn alumni organizations into the mid-1950s. In the homosociality of these male-only institutions, Milton clearly found sorely needed human intimacy. Whether his intimacy with other boys and men ripened into an active sexual life at this time is unclear.

Having worked as a copy boy for the Philadelphia Public Ledger during the summer after his freshman year at Penn, the precocious young collegian was soon promoted to writing book and theater reviews by the paper’s newly-installed literary editor, Walter Yust, a Jewish Penn graduate a dozen years Milton’s senior who took the young man under his wing. Yust would become the subject of his grateful protégé’s dedication of his third detective novel, The Boudoir Murder (1931), which read in part: “To WALTER YUST For Whose Friendship and Kind Advice…I Am Deeply Appreciative.” After graduation Milton enrolled at University of Pennsylvania Law School, where he served as an Associate Editor of the Law Review and received his J. D. degree at the age of twenty-two in 1929. This was the same year, incidentally, in which Milton’s fellow Pennsylvanian, famed mystery writer John Dickson Carr—a far more indifferent student only three months younger than Milton—ignominiously left Haverford College, located about eight miles to the northwest of Penn, without a degree.

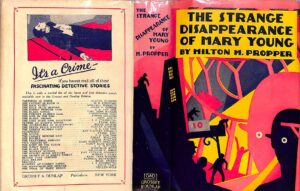

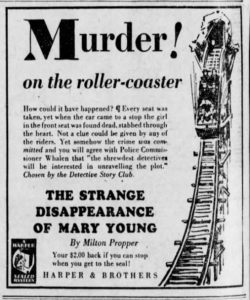

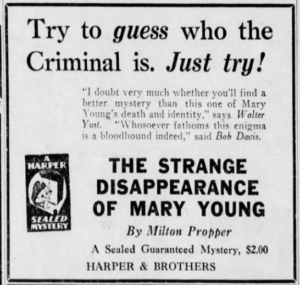

Although he qualified for the bar the same year in which he graduated from law school, Milton never hung out a shingle, having to wide acclaim and sales published, while still a student at Penn, his first detective novel, The Strange Disappearance of Mary Young (1929), with the publishing firm Harper & Brothers. Milton’s debut mystery detailed the dogged investigation by handsome young Philadelphia police detective Tommy Rankin into the outré demise of a beautiful young woman found stabbed through the heart in a car at the “Thrills in the Dark” scenic railway ride at Woodlawn Park. The author based the scene of his crime on a popular real life amusement attraction, a roller coaster built inside an artificial mountain, located north of Philadelphia at Willow Grove Park. The previous year Milton had serialized his novel, which he had completed in just two months during the summer of 1927, when he was merely twenty years old, to great publicity and acclaim in Pictorial Review.

Having commenced reading mysteries around the beginning of the 1920s at the tender age of fourteen, Milton soon became addicted to the tantalizing stuff. By decade’s end he estimated that he had read some six hundred and fifty detective novels, at the rate of about sixty-five a year, or more than five a month. Thus writing mysteries seemed to him a natural next step. “I decided I could write better ones [than many of the ones I was reading],” he told an Akron, Ohio interviewer in 1930. He actually preceded into print with a detective novel, by a single year, his similarly precocious contemporary John Dickson Carr.

The proud young author dedicated The Strange Disappearance of Mary Young “To MOTHER who is largely responsible for this book,” just as the following year he would dedicate his second novel, The Ticker Tape Murder, “To my sister MADELYN whose interest and encouragement have been invaluable.” Helen and Madelyn were the only family members whom Milton ever so honored, although he also dedicated books to Cass Canfield, president and chairman of Harper (“My Most Friendly Critic”) and Walter Yust, as well as, collectively, the entire Penn Law School Class of ’29 and his brothers at Sigma Lambda Pi, lately merged into Phi Epsilon Pi, which Milton acknowledged too for good measure. With not only large book sales—publisher Harper & Brothers’ advance printing numbered a hefty ten thousand copies—but a film version of Mary Young in the offing as well (though in the event the film failed to materialize), Milton seemingly had ample reason to believe that a gilded career as an author of detective fiction lay ahead of him, as it certainly did, we know in retrospect, for John Dickson Carr. “Writing detective stories is so fascinating and lucrative,” his Akron interviewer explained, “that [Propper] won’t practice law, at least for the time being.”

This was, after all, 1929, the year when highbrow detective novelist S. S. Van Dine, having successively placed three mysteries on the American bestseller lists, had published yet another, The Bishop Murder Case, which became the most successful and eagerly discussed of them all. All four of Van Dine’s detective novels were as well made into hit films, wherein the author’s suave amateur sleuth Philo Vance was swankily played by, respectively, matinee idols William Powell and Basil Rathbone. The success of the Van Dine novels also famously inspired two other clever young Jewish males in the northeastern United States, themselves just a year older than Propper, Daniel Nathan and Emanual Benjamin Lepofsky (aka Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee), to write mysteries under the joint nom de plume Ellery Queen, the first of which, The Roman Hat Mystery, also appeared in 1929. The field of mystery writing, like the American economy generally, was booming. What could go wrong?

Milton Propper may have been inspired by the heady American success of S. S. Van Dine, but when it came to mystery writing the young man admitted to being something of an Anglophile, decidedly impressed with the skill which British authors evinced at the complex fair play puzzle plotting that he so admired. Doubtless a 1929 trip to England he made with his parents and sister augmented the young author’s literary Anglophilia. Yet he also singled out for praise another American detective writer, Isabel Ostrander, who has languished in obscurity for nearly a century now, since her premature death in 1924.

“I am in complete agreement with you as to the general superiority of English detective stories,” he confided in correspondence with noted American mystery fan Percival Mason Stone in 1931, “especially those of Lynn Brock and [Freeman Wills] Croft[s], who also happen to be my favorite authors, though I would exclude [J. S.] Fletcher’s third-rate tales of the past five years. But in defense of America, I would suggest the late Isabel Ostrander, who ingenuity and plotting were unsurpassed.” As a neophyte mystery reader, Milton explained to his Akron interviewer in 1930, “[m]y favorite mystery story writers then were Anna Katherine Green and Isabel Ostrander”—American women authors whom, along with Carolyn Wells, John Dickson Carr as a youngster had greatly admired as well, although several decades later Carr referred to them dismissively as “lost ladies now well lost.”

To a Reading, Pennsylvania journalist in 1929 Milton, sounding a great deal like John Dickson Carr, propounded his belief in the fair play puzzle as the raison d’être of the detective novel. “The peculiar fascination in a murder mystery is the direct challenge it offers to the mind of the reader,” he explained. “It is as though the author says to him, ‘I’m cleverer than you and I intend to fool you; and the reader accepts the gauntlet. A royal battle is on, at once, with the solution as the prize and the reader determined to reach it ahead of the detective.”

Reviewers roundly praised The Strange Disappearance of Mary Young for its author’s deft playing of the murder game according to the fair play rules which had been laid down by S. S. Van Dine in the United States and Father Ronald Knox in the United Kingdom. “The writing might be smoother and the characters more clearly drawn,” allowed a crime fiction critic in the Camden, New Jersey Courier-Post, who contended nevertheless that the novel “has the one outstanding merit of playing fair with the reader and fooling him at the same time. When the grand climax arrives—there is real surprise, not disappointment.”

Reviewers roundly praised The Strange Disappearance of Mary Young for its author’s deft playing of the murder game according to the fair play rules which had been laid down by S. S. Van Dine in the United States and Father Ronald Knox in the United Kingdom. “The writing might be smoother and the characters more clearly drawn,” allowed a crime fiction critic in the Camden, New Jersey Courier-Post, who contended nevertheless that the novel “has the one outstanding merit of playing fair with the reader and fooling him at the same time. When the grand climax arrives—there is real surprise, not disappointment.”

Yet another reviewer raved of the novel: “Of all the detective stories I have read recently (over one hundred and twenty-five of them), this book stands out as one of the very finest….Mr. Propper…displays due regard for the rules of detective fiction and….knows how to create suspense, atmosphere and ingenious situations….” Even New York City Police Commissioner Grover Whalen added his voice to the chorus of praise for the novel, in a highly touted blurb avowing: “The shrewdest detectives will be interested in unraveling the plot.” Unfortunately Whalen’s words largely lost their persuasive appeal the next year when he ordered his police brutally to suppress a March 6 labor demonstration, an action which compelled his resignation.

Part of the attraction as well of Mary Young surely was that, when it was published on April 3, 1929, it became the fifth novel in publisher Harper & Brothers’ enticing, if admittedly gimmicky, “Sealed Mystery” series, wherein readers were boldly promised that if they could bring themselves to return the novel to the bookseller with the seal around the final chapters unbroken, leaving the case “unsolved,” as it were, they would receive their money back. The man behind this clever sales gimmick, Eugene St. Rose Reynal, who later founded the firm of Reynal & Hitchcock and published such admirably original works as Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince (1943), Lillian Smith’s Strange Fruit (1944), Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano (1947) (though he would become notorious for turning down J. D. Salinger’ 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye), boasted a few weeks after the publication of Mary Young that to date only three copies of Harper sealed mysteries had been returned, seals unbroken.

Immediately preceding Mary Young into print in March 1929 in the Sealed Mystery series was Lynn Brock’s The Stoke Silver Case (in the UK The Dagwort Coombe Murder), while following it into print later that year were Brock’s Murder at the Inn (in the UK The Mendip Mystery) and Freeman Wills Crofts’ The Purple Sickle Murders (in the UK The Box Office Murders). John Dickson Carr’s own debut mystery, It Walks by Night, would appear in the series the next year, along with Lynn Brock’s Murder on the Bridge (in the UK Q.E.D) and Freeman Wills Crofts’ Sir John Magill’s Last Journey. It was an impressive criminal company indeed. Between 1929 and 1943 Harper would publish all fourteen of the Milton Propper detective novels (as they did, over a much longer period, the John Dickson Carr novels).

Immediately preceding Mary Young into print in March 1929 in the Sealed Mystery series was Lynn Brock’s The Stoke Silver Case (in the UK The Dagwort Coombe Murder), while following it into print later that year were Brock’s Murder at the Inn (in the UK The Mendip Mystery) and Freeman Wills Crofts’ The Purple Sickle Murders (in the UK The Box Office Murders). John Dickson Carr’s own debut mystery, It Walks by Night, would appear in the series the next year, along with Lynn Brock’s Murder on the Bridge (in the UK Q.E.D) and Freeman Wills Crofts’ Sir John Magill’s Last Journey. It was an impressive criminal company indeed. Between 1929 and 1943 Harper would publish all fourteen of the Milton Propper detective novels (as they did, over a much longer period, the John Dickson Carr novels).

Although Milton Propper never attained the fame of S. S. Van Dine, let alone his fellow youngsters John Dickson Carr and Ellery Queen (whose own writing careers, the Great Depression notwithstanding, blossomed like black roses in the Thirties), his novels were published not only in the US but in the UK and they received generally good notices in both countries, although reviewers of the later books, reflecting changing tastes, carped with increasing frequently of slow pace and flat characterizations. His earlier novels also were serialized in American newspapers. “You can always expect a substantial and workmanlike detective story when Milton Propper sits down at his typewriter,” approvingly observed future Pulitzer Prize winning historian Bruce Catton in his 1935 review of Milton’s One Murdered, Two Dead in his nationally syndicated book review column.

An anonymous notice of Milton’s The Ticker Tape Murder in the Saturday Review of Literature from five years earlier judiciously laid out the author’s considerable virtues as a “fair play” detective novelist: “One of the main functions of a murder story is to mystify. This novel certainly does so and coupled with this is a very readable if plain prose….Mr. Propper has undoubtedly done a very good job. He has played the game with the reader according to all the…rules….the murderer is introduced early and all the clues that are available to the detective are available to the reader at the same time.”

Over the years, however, Milton Propper’s pace proved insufficient for him to maintain a viable independent mystery writing career. At this time, before the launching of the paperback revolution, crime writers did well to sell three thousand hardcover copies of any given title, mostly to rental libraries, thrifty Depression era readers preferring to borrow mysteries rather than purchase them. The pleasing prospect of a Mary Young did not come along every day. For about a decade Milton derived his primary income not from crime writing but from drudging it in federal government offices in Philadelphia and, during World War Two, Atlanta. With the publication in 1943 of his final detective novel, The Blood Transfusion Murders (which was possibly inspired by the death the previous year, following an abdominal operation, of his Uncle Julius at Roxborough Memorial Hospital), Milton gamely told the Atlanta Constitution that, while this would be his last mystery for the duration of the war, he would be back in print afterward. Sadly the novel, which received the poorest reviews of Milton’s career as a crime writer, instead became the last one he would ever publish.

When Milton returned to Philadelphia from Atlanta after the death of his parents the next year and attempted to rekindle his crime writing career, he found that Harper’s dynamic and influential new mysteries editor, Joan Kahn, had no interest in his now old-fashioned style of deliberate detective novel, ambitiously determined as she was to give crime fiction a major makeover in the sexy new style of fast-paced “suspense.” The initial brightly glowing promise of Milton’s mystery writing career swiftly guttered, with what proved, as we have seen, dreadful personal consequences. Outside of a 1944 digest paperback reprint by Crestwood of Milton’s 1940 detective novel The Station Wagon Murder and British editions of his detective novels The Blood Transfusion Murders and The Handwriting on the Wall (1941), published belatedly in 1947 and 1949 under the titles Murder in Sequence and You Can’t Gag the Dead, there were no further appearances of the author’s books in print over what remained of his life. Between 1956 and 1962, Milton methodically renewed the copyrights for his first six mysteries as they became eligible for such. The last of these delusive, last-ditch renewals, prophetically for The Family Burial Murders (1934), took place less than two months before Milton emptied a bottle of sleeping pills down his throat, putting an end for once and all to his earthly privations.

The World of Milton Propper

Some of the above biographical detail is drawn from “The World of Milton Propper,” an article which author Francis Nevinspublished nearly forty-five years ago in the July 1977 edition of The Armchair Detective, which in turn drew heavily on communications between Nevins and the late author’s sister Madelyn. The article has always been an odd piece to my mind, in the way it veers wildly from something less than half praising Milton Propper to rather more than half damning him, both as a writer and a person, in the weirdly schizophrenic manner of Nevins’ Edgar Award winning biography of Cornell Woolrich, First You Dream, Then You Die (1988).

Like his Woolrich biography, Francis Nevins’ Milton Propper article is composed of a little biography and a lot of plot analysis. Concerning Milton Propper as a detective novelist Nevins derides him for dull writing and characters crafted of “something less than one dimension,” while seemingly paradoxically allowing that “the man knew his craft well” and that his books “hold something of the intellectual excitement of the early Ellery Queen novels.” According to Nevins:

[Propper] likes to begin with the discovery of a body under bizarre circumstances, to scatter suspicion among several characters each of whom has a great deal to hide, to juggle clues and counterplots with dazzling dexterity. As a special attraction, Propper arranges his stories so that as often as possible he can introduce either some form of mass transportation, or some complex problem of succession to a large estate, and occasionally both in the same book. His delight in these subjects somehow penetrates even through his flat and stately style.

Milton Propper, in other words (mine, not Nevins’), was simply a Golden Age “Humdrum” detective novelist, this term having been coined by noted Silver Age British mystery writer and critic Julian Symons to describe detection-focused Golden Age mystery writers who, in his view, fatally neglected the loftier literary graces. I discuss three of the most successful British Humdrums, John Street, Freeman Wills Crofts and J. J. Connington, in my 2012 book Masters of the “Humdrum” Mystery; yet there were as well other, lesser-known Humdrums, British and American, many of them now forgotten with the passing of time. While Milton Propper has not disappeared completely down the memory hole, he nevertheless remains obscure to the vast majority of vintage mystery fans.

For fans of the workmanlike fair play Golden Age detective novel epitomized by Crofts, which puts a premium on the methodical investigation of a murder problem, Milton Propper still holds appeal…By his own admission, as we have seen, Milton Propper was a great admirer of Twenties British detective fiction, specifically referencing as one of his very favorite mystery authors Freeman Wills Crofts. Indeed, Propper’s detective fiction to me is quite obviously modeled heavily on Freeman Crofts. For fans of the workmanlike fair play Golden Age detective novel epitomized by Crofts, which puts a premium on the methodical investigation of a murder problem, Milton Propper still holds appeal—although Nevins’ Ellery Queen comparison is ill-advised, in my view, Propper, like other Humdrums, lacking Fredric Dannay’s higher flights of baroque detective fancy.

Over the last decade I and a few others have written about Milton Propper’s mysteries on the internet, but my effort to get his books reprinted has not been successful, my attempts to reach out to his family having to date proved futile. Did Milton Propper’s relations feel burned by Francis Nevins’ unkind article? If they did, I do not think it was so much because of Nevins’ handling of his subject’s sexual life—although this is bad enough, it seems to me, as Nevins frames the life of Milton Propper (“a poor, drab, haunted soul” to quote him) as that of a crudely stereotypical tragic homosexual with a mother fixation, just as he does with Cornell Woolrich, at much greater length, in his doorstop Woolrich biography. On the whole the subject of Propper’s sexuality remains an afterthought in Nevins’ article, leaving room for further exploration.

Rather I imagine that any Propper family chagrin might have been provoked over the way Nevins handles Milton Propper’s politics. Nevins in his article repeatedly bashes Milton Propper for what he deems the author’s retrograde social and political views. Here follow a few scathing excerpts from Nevins’ article:

He…flaunts like a medal of honor his belief that the rich and powerful can do no wrong, casually justifies all sorts of criminal conduct when perpetrated by the police….

Whenever a suspicion against someone crystallizes in [the mind of Propper’s sleuth, police detective Tommy Rankin], he himself or a subordinate proceeds to burglarize the person’s house for confirmatory evidence….Even when Rankin has no specific suspicions he still indulges in illegal searches….I leave it to historians to determine how many of the Watergate gang read these novels in their formative years.

This was the man who celebrated the perquisites of being born with money and justified the illegal acts of anyone with a badge on his chest.

After witheringly referring to what he terms the author’s “contempt for everyone who lacks money or power saturating every page” of his mystery The Election Booth Murder, Nevins allows that Milton’s sister Madelyn asserted to the contrary “that Propper’s social views were much more enlightened than his novels suggest—which shows once again how damnably difficult it was for an author to express any but the most reactionary sentiments in the classic detective novel.” Yet Nevins then repeatedly damns Milton Propper anyway for holding what he deems unpardonably reactionary views concerning the prerogatives of privileged members of the upper crust and their biddable minions in blue.

At the opening of his article Nevins thanks Madelyn for her “generous cooperation” which made it possible for him to attempt a sketch of the author’s life. But the sister whom Nevins thanked herself wrote a letter (printed, at least partially, in the next issue of The Armchair Detective, with no response from Nevins), in which she complained that Nevins had gotten her beloved brother’s politics all wrong: “My only comment is that you omitted a reference to my opinion that Milton was not hopelessly conservative. My immediate family, like the rest of our neighborhood and friends, were rock-ribbed Republicans, and Milton scandalized all by becoming an ardent Roosevelt supporter. He had a very great influence on me in those early, happier days, and my thinking by the time I went to college was slightly to the left of his.”

What Nevins seems not to have appreciated is how the things which so scandalized him about Milton Propper’s mysteries all characterize the writing of the author’s mentor of sorts from across the pond, Freeman Wills Crofts, especially in the 1920s, with the significant exception of Crofts’ occasional unattractive outbursts of antisemitism, which Propper for an obvious reason omitted to replicate in his own crime fiction. In Masters I wrote at length of the procedurally (and morally) improper behavior of Crofts’ police detectives—their illegal searches, their outright lies to suspects (or “bluffs” as Crofts euphemistically terms them) and their abuse of witnesses—as well as Crofts’ patronizing treatment of the working class and his regrettable penchant for heavily rendered dialect speech. In all of these failings I think Milton Propper was merely imitating his model Freeman Crofts—though of course neither man was exceptional among authors of Golden Age detective fiction in committing these particular transgressions. Nor, I might add, were real policemen. It seems unfair to single out Milton Propper for such intense and unrelenting critical flagellation.

Interestingly the prominent British crime fiction reviewer and fiendish crossword deviser who was wryly known as “Torquemada,” Edward Powys Mathers, came to precisely the opposite conclusion from the hectoring Nevins concerning Propper’s alleged authoritarian tendencies, approvingly declaring in his review of the author’s The Election Booth Murder (Murder at the Polls in the UK): “[Fictional] Philadelphia, I am glad to note, boasts a police force which is neither corrupt nor composed of blustering half-wits. This is, I suspect, due to the influence of Tommy Rankin, a quiet, decent fellow and a capable detective.” When he delivered this positive judgment upon Propper’s policemen, Torquemada doubtless had in mind the American hard-boiled school of mystery, which he like many other fastidious British reviewers of the time, tended to view with squeamish distaste.

We can fault Milton Propper for too slavish devotion to his literary master, to be sure, but to attribute to the author himself all of the retrograde views which Nevins so scornfully enumerates (some of them perhaps not so retrograde as we like to think) strikes me as unjust, especially given Madelyn’s claims about her brother’s politics, which seem to have been true. We can get a better picture of the politics of Milton Propper by taking a closer look at the detective novel which Torquemada mentions above: The Election Booth Murder, published by Harper shortly before Election Day in October 1935, amid the depths of the Great Depression.

III. Milton Propper and The Election Booth Murder

In 1926 wealthy Republican building contractor and machine politician William Scott Vare, dubbed the “boss of Philadelphia,” was elected to the United States Senate, in a contest mired in a nasty murk of accusations of voter fraud and civic shenanigans. The losing Democrat dramatically charged that there had been “massive corruption” on Vare’s side, with the venal boss and his crooked supporters having shamelessly “padded registration lists, misused campaign expenditures, counted votes from persons who were dead or never existed and engaged in intimidation and discouragement of prospective voters.” In one particularly outrageous example of political chicanery, Philadelphia Sheriff Thomas “Big Tom” Cunningham managed miraculously to make a $50,000 donation to the Vare campaign on his annual salary of $8000. (See Ken Finkel’s November 27, 2017 article “The Never-Seated U. S. Senator from Philadelphia,” at The PhillyHistory Blog.)

The state’s governor, progressive patrician Republican Gifford Pinchot, who that year had lost to William Vare in the GOP senate primary, refused to certify Vare as the winner, leading to a three-year Senate investigation of the contest. Having barely survived a stroke in 1928, the partially paralyzed Vare was summoned to the Senate the next year and sternly informed that he would not be seated. “The fraud pervading the actual count by the division election officers is appalling,” the investigating Senate committee concluded. “The average Philadelphia voter had a one-in-eight chance of having his ballot recorded accurately on Election Day.”

In 1930 an enraged William Vare spitefully endorsed the Democratic gubernatorial candidate over Governor Pinchot, who was running for reelection, but to no avail. Three years later, on Election Day, November 7, 1933, Philadelphia Democrats, who had been eclipsed from power in the city for more than eight decades, won the municipal election, following several years of the Depression and the promise of a “New Deal” from newly-inaugurated US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Vare saw himself ousted as head of the Republican Central Campaign Committee of Philadelphia in June 1934, just a couple of months before his death at age sixty-seven on August 7, a day after the twenty-eighth birthday of the politically engaged Milton Propper, an ardent devotee of FDR and the New Deal who, writes Nevins, was prone to “prowl” (Nevins’ word) late-night diners and automats, “taking soundings” of patrons.

The political brouhaha in Pennsylvania obviously inspired the writing of Milton Propper’s seventh detective novel, The Election Booth Murder, which concerns the fatal shooting of a reform political candidate on Election Day in Philadelphia. The murder victim, Sidney Reade, is running for city District Attorney not as a Democrat but as a member of the “Popular Party,” while his opponent, venal Sheriff Leon Connell, is of the “Regulars,” not the Republicans; yet despite this obfuscation I imagine the implications were clear to mystery readers at the time—at least if they lived in Pennsylvania. When Propper writes that “[t]o Philadelphians, for the last quarter of the century, there was only one boss—Harvey Warren, erstwhile national senator, party leader of the Regulars, and the unchallenged czar of politics in eastern Pennsylvania,” people perusing the book surely would have recognized the allusion to William S. Vare.

In his article Francis Nevins castigates Milton Propper as a snobbish, bootlicking authoritarian, yet Madelyn insisted to the contrary that her brother was a political idealist full of admiration, as were so many young people at the time, for the sweeping New Deal reforms proffered by the first administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. I think that surely Propper’s sister had a better grasp in the facts than Nevins, who never knew the Milton Propper and was writing about him at second hand fifteen years after his death in 1962. In fact correspondence which Propper wrote to Time magazine in the Thirties shows him praising FDR and condemning Philadelphia’s machine politics. A loathing of political corruption pervades The Election Booth Murder. Certainly Propper does not have the visceral quality of Dashiell Hammett (his formal, deliberate prose is far more redolent of Freeman Wills Crofts), but in its modest way The Election Booth Murder paints a strong picture of urban malfeasance.

Today of course we would be more likely to see Republicans criticizing urban Democratic “machines” and screeching about rigged elections, but in the Philadelphia of Propper’s day it was Republicans who were running the show and long had been, although their machine was facing terminal breakdown. (The GOP elected its last mayor in Philadelphia in 1947.) In 1935, the year of Propper’s publication of The Election Booth Murder, Republicans faced a strong challenge in the mayoral race that year, the Democratic nominee being popular John B. “Handsome Jack” Kelly, Sr., brother of playwright George Kelly, father of future Hollywood actress and European royal princess Grace Kelly and himself a wealthy building contractor (though one, in contrast with William Vare, of Irish Catholic descent).

A Great War veteran and Olympic rowing champion, “Handsome Jack” Kelly lost the election by some 45,000 votes, vastly less than the usual losing margin for Democrats of 300,000. (Four years earlier the Democratic mayoral candidate in Philadelphia had received only 10% of the total vote.) The Kellys, incidentally, resided in a handsome colonial house built by Handsome Jack in 1929, the same year his daughter Grace was born, located about a mile from the colonial house where the Proppers lived in Roxborough. It was recently purchased by Princess Grace’s son, Prince Albert II, with the plan of turning it into a house museum. The Propper home, incidentally, is now a Forever Friends daycare center.

This historical background gives resonance to Milton Propper’s mystery. Like his model Freeman Wills Crofts, Propper may not have been strong on characterization, but he was always pleasingly precise with his settings. When Detective Tommy Rankin of the Philadelphia police force is sent to help monitor voting at the 52nd Ward station in South Philly (trouble is expected from gangs of toughs at the polls), this is how Propper describes the scene:

Like many houses in that vicinity, [the voting station] was untenanted and dilapidated, in temporary use only, for the elections. On the corner, it fronted Mifflin Street, with a weathered porch of sagging boards, unpainted for years. It was two stories high, of faded red brick; the windows were dirty and many panes were missing. A thin line of patiently good-natured people trickled into its murky interior. Outside, the walls and convenient posts held their usual placards, pictures of respective candidates, instructions for balloting, and assessors’ lists. Little groups gathered on the pavement: neighbors passing the time of day; loungers inevitably attracted to the polls; and politicians, embryo or otherwise, pressing their special interests on bewildered voters.

Shortly afterward the Popular Party’s DA candidate is shot through a window as he votes and all hell promptly breaks loose. Is dogged Tommy Rankin up to solving a dastardly political hit job? No fear, readers! You can be certain that Propper’s Detective Rankin, like Crofts’ Inspector French, will ultimately catch the cunning killer. While I concur with Francis Nevins that The Election Booth Murder is not Milton Propper’s best detective novel, I find it an enjoyable example of the formal investigative detective novel, composed along Croftsian lines.

New York Times Book Review columnist Robert Van Gelder carped, to be sure, that in The Election Booth Murder Propper placed too much emphasis on “reportorial exactness.” Yet Booth is a proto-police procedural sort of crime story; and that is something a reader either will like, or not. For its part the Minneapolis Journal praised Propper for providing “much lore about rackets and other vice, together with a scholarly review of the political situation, all in readable vein” with “Tommy Rankin…working at top form.” In my case The Election Booth Murder affords pleasing cogitative diversion while affording an intriguing faded snapshot of a place in time, one perhaps of some relevance today.

POSTSCRIPT: “Any borrower who retains a book beyond the allowed time shall pay….”

Until the more venturous vintage mystery bloggers began talking about the detective fiction of Milton Propper during the last dozen years, the author’s name last surfaced, so as far as I am aware, in an October 27, 1980 newspaper article in the Nashville Tennessean. On what was evidently a rather slow news day, the Nashville Tennessean reported—on the front page, no less—that a brittle black book, overdue at the Nashville Public Library for half a century, had been discovered in a partially-demolished garage in the city. This book was Milton Propper’s The Ticker Tape Murder. Queried about the matter, a local librarian estimated that in modern value fines for the book would amount to some $36,000. Tragically for library coffers no one knew anymore who actually had “borrowed” the book back in 1930, when it was hot off Harper’s press. The aforementioned librarian opined—a mite gratuitously, it seems to me—that “The Ticker Tape Murder may have been gripping reading back in 1930, but it’s doubtful that it would be popular today.” I believe this man spoke presumptuously, however. Today, over forty years later, we have within ourselves more respect, and indeed more genuine admiration, for our distinguished mystery writing forebears from the Golden Age of detective fiction.

Requiescat in pace, Milton Morris Propper. You may not have lived up to your early gilded promise, but you deserved much better, both from the past and from posterity. The latter we can still do something about, I hope.