“Louise Penny,” was, at first, the sum total of what I blurted out yesterday to the interviewer wanting to know what might have influenced my new novel A Bend of Light. So many more names I’d meant to list right away in a long, lyrical response that would show both my gratitude to some favorite writers and maybe also make me sound deeply wise and well read.

I’d planned to be eloquent and intellectually dazzling, of course, as one always plans, in addition to charming and funny and at least marginally coherent. I’d meant to speak compellingly about my novel’s setting, a fictional village on the coast of Maine—much like the small towns of Penny or William Kent Krueger—and its struggling female protagonist, a former photographic interpreter in WW2 who must start life over again in the hometown she fled years ago.

And I’d definitely meant to grunt out more than two words.

This, by the way, is why Daphne Du Maurier, author of Rebecca, insisted, “Writers should be read, but neither heard nor seen.” When asked to voice our thoughts on the spot, writers cannot be counted upon to be eloquent or sometimes even intelligible—and we may not have remembered to brush our hair before a public appearance. We are accustomed to channeling words through our fingers onto pages where, if worse comes to worse, they can be coaxed and corralled and made to make sense, if only by our beloved editors.

At the very least, I could’ve begun talking about A Bend of Light and mysteries in general by recalling that tattered copy of Agatha Christie’s Curtain left by some former occupants at a beach condo, that book pulling me so hard into its pages I could not make myself go back in the ocean again until I’d finished, despite my skin charbroiling in the summer South Florida sun. I could’ve talked about much later discovering that even more than the thrill of the whodunnit, I was drawn to authors who explored the backstories and psychological states and cultural struggles of the suspects, all the festering jealousies and resentments and abuses that could turn a person’s heart toward violence.

Because gradually, over the years, I discovered that what I really wanted to read and to write was a good whydunit.

Despite my remarkably unhelpful grunting response yesterday to the poor interviewer, I do love to talk about an ever-growing list of authors who do this brilliantly, and whose work I learn from in writing my own novels. I could no more rank order my favorite writers than I could my own children or friends. In fact, even in listing these, I’m in near physical pain to leave so many out. Still, here are five mysteries that include all the twists we expect of a good whodunit, while also diving deep into what it means to be human, and the ways in which the inequities, privations and privileges of our own cultures can shape us.

A Great Reckoning by Louise Penny

I realize there are people in this world who like to read book series in order, and I can respect that. I’m just not one of them. I read my first Louise Penny book at the suggestion of a friend, and it was love at first page for Penny’s protagonist Armand Gamache and me—although the devotion is admittedly one-sided. I was late to the party with the Canadian author Penny, who was already widely acclaimed and on her twelfth novel A Great Reckoning. It was my first of hers, and I became obnoxious in my attempts to convert every literate person I knew into a fan. So much of what she does is brilliant, not least of which is her insight into what makes people tick…and suffer. And heal from unspeakable loss. Or not heal. And therefore plot to kill.

Start at the beginning of the series if you’re one of those organized, sane sorts of readers, but the truth is, starting anywhere in the Three Pines series is so very worth the journey.

Ordinary Grace by William Kent Krueger

William Kent Krueger also sets his novels—at least the ones I’ve been privileged to read—in a small town, in his case the north woods of Minnesota. Probably best known for his gripping Cork O’Connor series, he is remarkable handling the intricacies of detective fiction and also character development. The protagonist Cork O’Connor himself wrangles with his own dual identity as both Irish and Ojibwe, and those cultural tensions enrich this series. But my favorite book of his remains Ordinary Grace, a gorgeously gentle story with poetic prose that somehow still hurtles the reader forward to uncover the layers of lies, deceit and murder that the young protagonist encounters.

Devil in a Blue Dress by Walter Mosley

Like Krueger, Mosley doesn’t shy away from cultural and racial tensions, and his fiction throbs with life for many reasons, but at least in part because of those very tensions. Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins is the WW2 veteran turned private investigator in late 1940s Los Angeles. The first in the bestselling series, Devil in a Blue Dress presents an array of complex characters. As in all the best storytelling, Rawlins’ allies may turn out to be enemies, and at least one would-be villain may have a past that could change everything about our perceptions of guilt. A National Book Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award winner, Mosely manages to keep the reader both extraordinarily entertained but also, without slowing the story’s pace, contemplating the great existential questions of the soul and of our common society.

Pardonable Lies by Jacqueline Winspear

Jacqueline Winspear, like Walter Mosley, features characters who’ve been shaped and often damaged by war. Winspear’s fictional investigator and psychologist Masie Dobbs is a veteran of the Great War—and later of WW2. She continues throughout the series to deal with trauma from what she has endured and all she has lost. A costermonger’s daughter who later attends Girton College at Cambridge, Maisie can navigate both impoverished London alleyways and lavish, aristocratic estates. Trained to see beyond mere events and actions, Maisie analyzes not just the lives cut short by the deranged or the last whereabouts of missing persons, she focuses even more on the unremarkable, everyday cause that might’ve driven the violence or the disappearances: the harm ordinary people cause one another. One character, for example, [spoiler alert] has been so destroyed by the rejection and disdain of his father when it became clear the character was attracted to men, he has allowed himself to be presumed dead since a WW1 plane crash and has since lived tragically alienated from his family.

Again, start with the first of the series if you must, but this third is one of my favorites.

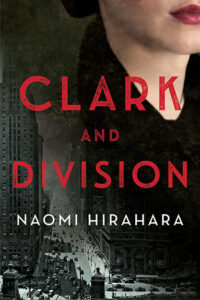

Clark and Division by Naomi Hirahara

Hirahara spent thirty years researching this novel, and it shows in all the best ways. A New York Times Best Mystery of the Year, Clark and Division refers to the area of Chicago where the Ito family is relocating after being released from Manzanar, the U.S. government’s detention camp for Japanese citizens during WW2. As twenty-year-old Aki Ito searches for answers about her revered older sister’s death, which authorities have labeled a suicide but Aki suspects was murder, the story unfolds in multiple layers. Hirahara’s own parents were survivors of the Hiroshima bombing, and perhaps partly because of her family’s story, the author explores history not as dusty old facts but as mystery, crevices of human experience we’ve not always explored fully or well. In Clark & Division, she has woven a story that is both captivating historical fiction and thriller

***