You’ve Got Mail is a many splendored thing: a fascinating, variegated film that braids together themes of hope and despair, friendship and heartbreak, love and hatred, preservation and destruction, resistance and surrender, technology and analogs. It is a depressed capitalist critique, a doting literary pastiche, a valentine to New York City, a paean to mom-and-pop-shops, a tortured love story, a nervous prognostication about the digital world to come. It is everything, except maybe a murder mystery. It is not a murder mystery. Except it almost was, a little bit.

This undeveloped twist elaborates on one of (I think) the most relatable moments in You’ve Got Mail—or, really, any Nora Ephron film. Our heroine, Kathleen Kelly (Meg Ryan), arrives to work at the Upper West Side children’s bookshop she owns and her employees are eager to hear about the blind date she went on the prior evening—to meet her anonymous e-mail pen pal. But Kathleen has been stood up, and her friends Christina (Heather Burns) and George (Steve Zahn) are eager to help her pinpoint a viable reason.

“Maybe there was a subway accident,” Kathleen says, and Christina agrees, adding that he probably got sucked onto the tracks. “Maybe he had a car accident,” Kathleen says. “Those cab drivers are maniacs.” Christina agrees again: “They hit something and you slam right into that plastic partition!” They keep finishing each other’s sentences, building a tragic story that might explain his absence. But George has seen today’s copy of The New York Post and is desperate to get their attention—sputtering as he tries to get a word in edgewise.

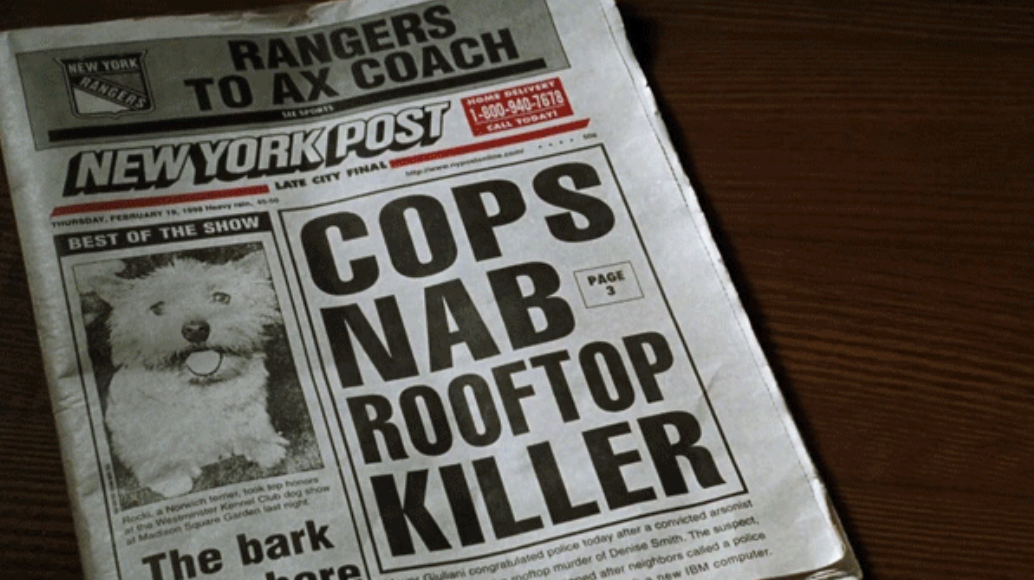

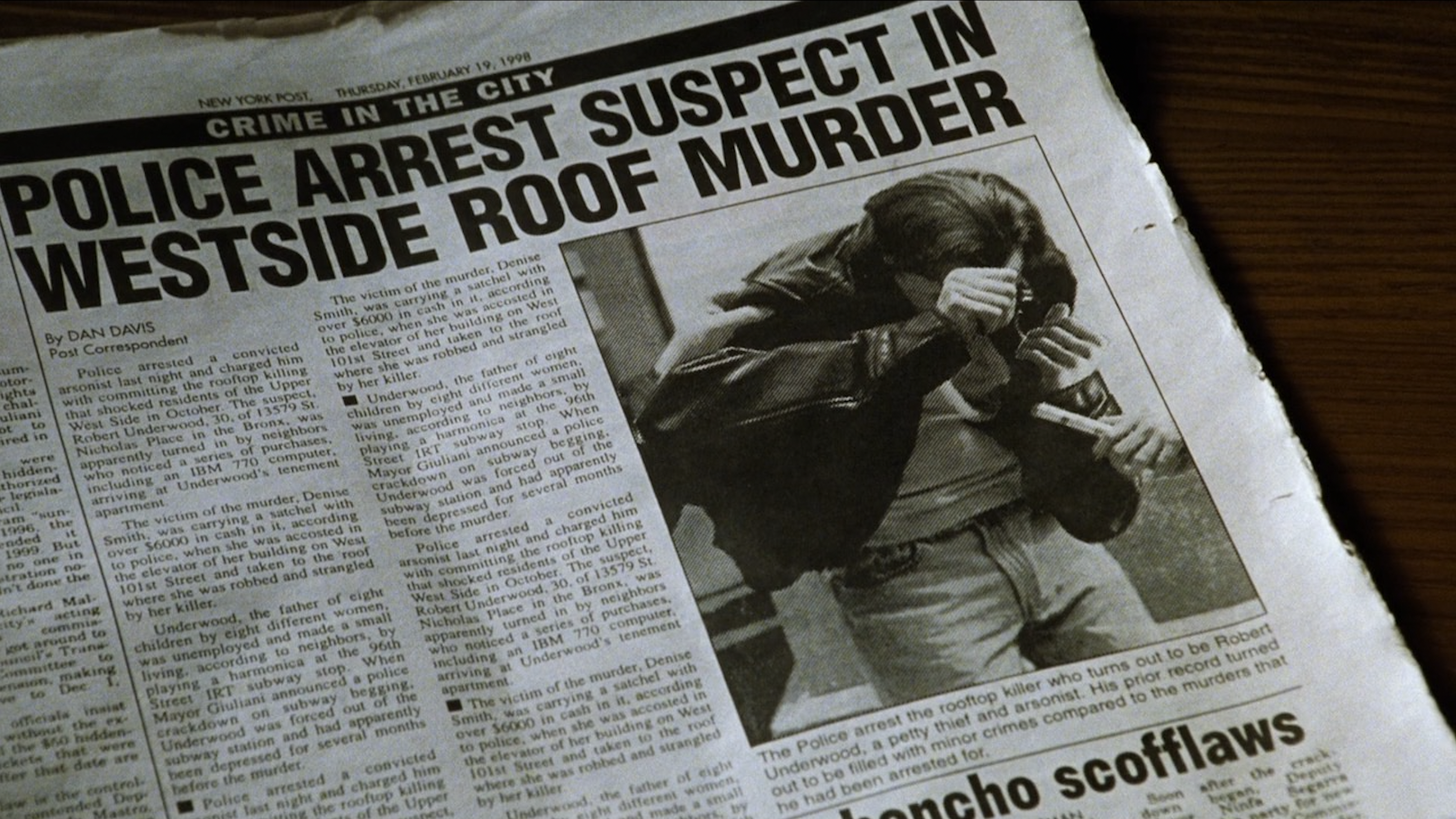

“What?” Kathleen finally asks him, but George can’t answer. He can only throw the newspaper down on the countertop. The camera cuts to the front page long enough for the boldface headline to sink in: COPS NAB ROOFTOP KILLER.

“What are you saying?” Kathleen asks George, slightly defensively.

“It could be,” George answers. “He was arrested two blocks from the cafe.”

They frantically flip through the paper, looking for a photo. There isn’t much of one, but it satisfies Christina. “So that explains it,” she says. “He was in jail!” finishes George. “You are so lucky,” says Christina. “You,” adds George, “could be dead.”

Still, Kathleen remains unconvinced. “He couldn’t be the Rooftop Killer!” she hisses. Veritably, he is not; the real identity of Kathleen’s secret anonymous pen pal is her nemesis, bookstore magnate Joe Fox (Tom Hanks). Joe, who had arrived at their meeting place at the appropriate time, has seen Kathleen and realized that she is the unknown woman with whom he has fallen in love, online. He approaches her, as Joe Fox, but she does not want to talk to him, so he pretends that they have bumped into one another coincidentally, leading her to conclude that her real date has simply not shown up.

Although Joe and the audience know the truth, any option is a viable one to Kathleen and her friends. Even though Kathleen doesn’t believe that her blind date could be the murderer who has apparently been terrorizing New York City, the circumstances do line up, somewhat. This is the first time in the film that the online, anonymous relationship she has with a stranger (whom she has previously met in a chat room) is presented in a non-rosy light. She doesn’t really know who he is, she realizes now. She has no clue. He might be a creep. He might be a lunatic. He might be a danger to her.

In the film, this is a throwaway moment, a brief, anxious acknowledgement of plausible treacherousness in an otherwise romantic film. It’s also a symbolic moment; Joe Fox is not out to murder Kathleen (or any woman), but he is out to wreck her business, her historic children’s bookstore. Although he doesn’t kill her, when he causes her to close the store, he does kill a part of her. It had been her late mother’s store, before it was hers. Joe has quashed her livelihood and taken away the place where she grew up.

As it stands, You’ve Got Mail allows this glimmer of danger to be a thoughtful thematic harbinger about Joe’s effect on Kathleen’s life. But an earlier version of the script features an entire subplot dedicated to the pursuit of the Rooftop Killer, and related imperilments at the hands of men.

You’ve Got Mail, co-written by Nora Ephron and her playwright sister Delia Ephron, is based on Ernst Lubitsch’s 1940 film The Shop Around the Corner as well as that film’s source material, the 1937 Hungarian play Parfumerie by Miklós László. The inclusion of the Rooftop Killer in the modern retelling, which premiered in 1998, certainly gives it a world-wise cynicism befitting a culture that had spent the previous six years watching Dateline.

But the earlier version of the script blows this up; the investigation into the identity of the Rooftop Killer pervades the narrative. The Rooftop Killer has committed a murder on the rooftop of George’s apartment building, and he falls passionately in love with the detective on the case, Meredith Carter of the 23rd Precinct. She interrogates him about suspicious activity in his building, but her questioning is derailed by George’s (welcome) advances. The scene proceeds as follows:

INT. COFFEE SHOP – DAY

George and Meredith are sitting in a booth.

MEREDITH

Mr. Pappas, I’m investigating the murder

of the woman found on the roof of your

building. Do you live alone there?

GEORGE

Do I live alone? Yes I do. Do you live

alone?

MEREDITH

Yes.

George takes her hand in his and looks at it as if it were

the eighth wonder of the world. He starts stroking it,

caressing it…

Meredith pulls it away. A beat. Then she gives it right

back to him. He continues stroking. They stare at each

other. He puts her fingers into his mouth.

MEREDITH

(overwhelmed)

What are you doing?

GEORGE

I don’t know. I have no idea.

MEREDITH

You have to stop.

GEORGE

I can’t.

She utters a little moan.

INT. GEORGE’S APARTMENT – A SHORT WHILE LATER

They come into the apartment. She throws herself into his

arms.

The rest of the serial killer plot is virtually immaterial; Meredith and George fall passionately in love and the Rooftop Killer is caught, later. But it reveals a greater interest in “serial killers” more than the film’s final iteration. In the film, this scene merely provides a realistic reaction. It makes sense for a modern woman speaking to an unknown man online to wonder if he poses a threat, more than it does for this interaction to intertwine with an actual serial killer manhunt, as in the first version of the screenplay.

But, see, You’ve Got Mail is not the first Ephron comedy to include an unexpected serial killer in the background. The 1994 film Mixed Nuts, directed by Nora Ephron and once again co-written with her sister Delia, is a Christmastime-set, ensemble-esque romantic comedy with its own murderer: “the Seaside Strangler.” This film, which is based on a 1984 French film called Le Père Noël est une ordure, takes place in the office of a nearly out-of-business suicide hotline on Christmas Eve. Their small California town is terrorized by a serial killer. But the organization has bigger problems.

Steve Martin plays its hapless leader, Philip, trying to save the hotline from eviction while also finally coming to terms with his feelings for his kindly coworker Catherine (Rita Wilson). Throughout the course of the evening, they, along with neighbors and colleagues (played by Madeline Kahn, Juliette Lewis, Robert Klein, Adam Sandler, Anthony LaPaglia, and Liev Schreiber), fall in love, try to save their business, work out their own issues, and learn to accept themselves. It’s an odd film, perhaps a little too madcap but big-hearted and full of genuine laughs.

But it is also tinged with danger; the film acknowledges many times the potential jeopardy of having in-depth conversations with strangers over the phone. People call the hotline terrified that the Seaside Strangler will kill them, even if they bear no resemblance to his victims. Creeps call the suicide hotline, including one particularly sexually aggressive lunatic who always wants to speak to women. The operators are told never to reveal the business’s address or their own personal information, and the one time Philip does, to a weeping-sounding Liev Schrieber, it seems inevitable that Philip has given their location to the Strangler. (Actually, Schreiber’s character is a lonely transgender woman named Chris, who winds up being loved and accepted for who she is by the group, by the film’s end.)

Similarly, the original script of You’ve Got Mail acknowledges the precariousness of its heroine more than the final cut. In one respect, the original script of You’ve Got Mail participates in a more ensemble-focused version of the story—as in Mixed Nuts, the film gives almost every member of the community their own personal story. In this script, not only does George get to fall in love, but Christina also looks for a boyfriend, Joe’s girlfriend Patricia Eden (the great Parker Posey) finds her own kind of self-fulfillment through a new interest in Judaism, and Kathleen’s boyfriend Frank Navasky (Greg Kinnear) semi-stalks one of his literary idols, a reclusive writer named William Spungeon (a character cut totally from the final film but played by Michael Palin).

But this first version of the script is also more dangerous on the whole; when Patricia is on a ride home from a book event, a man insists on riding in her cab with her and doesn’t take no for an answer. We learn that Christina is a runner and Kathleen advises her to meet a man while she’s on a run, but later, it’s revealed that the victim of the Rooftop Killer was found in running clothes. And William Spungeon, the reclusive writer Frank idolizes (and follows around New York), offers to help save the Shop Around the Corner, but has ulterior motives. Kathleen leaves the store one night and finds him outside, where he grabs her and attempts to kiss her against her wishes. She kicks him in the shins in order to free herself. The scene reads as follows.

EXT. SHOP AROUND THE CORNER – NIGHT

It’s starting to rain. Kathleen lowers the grate over the

store. As she turns to walk away, William Spungeon steps in

her path out of the shadows.

KATHLEEN

Oh my goodness, hello. What are you

doing here.

SPUNGEON

Loitering. Lurking. Skulking.

Stalking.

He laughs. So does she. Dramatically, he whips out an

umbrella and opens it over the two of them.

SPUNGEON (cont’d)

You look very beautiful.

KATHLEEN

Thank you. But I’m a wreck.

He touches her cheek suddenly. Kathleen starts. Then he

blows on his hand.

SPUNGEON

An eyelash. It’s gone.

Kathleen relaxes. They start walking.

KATHLEEN

Are you writing another book?

SPUNGEON

I’m in the home stretch. I’ll be done in

approximately six more years.

KATHLEEN

Should I discount?

SPUNGEON

It’s about a man on a quest for knowledge

who meets a woman he cannot resist.

KATHLEEN

If I discount I have to fire someone

because I can’t discount with this

overhead but whom could I fire? I

couldn’t fire anyone.

Spungeon suddenly puts his hand through Kathleen’s hair. She

stops, frozen in place.

SPUNGEON

You have your mother’s hair. Thick,

wild, the color of Nebraska wheat.

He grabs her and tries to kiss her.

KATHLEEN

What are you doing? Let me go.

He backs her into a wall.

KATHLEEN

Stop it. Are you crazy?

She kicks him in the shins, wiggles free and runs away.

SPUNGEON

(calling after her)

If you change your mind, you can E-mail

me. Hermit@AOL.com.

In this version, most of the women in the film find themselves in a different New York than the famously charming cityscape of the film’s final cut. In this New York, men are menacing and forceful. It’s unclear, when a woman is approached by a man, if the encounter will turn out to be sinister—exemplified by the looming threat of the Rooftop Killer, much like Mixed Nuts’ Seaside Strangler. It’s only by luck that Patricia’s cab-mate turns out to be an obnoxious rabbi, or that the men Christina encounters on her runs are inaccessible.

In a version underscoring the duplicity and nefariousness of men, Joe does not fare so well, as a character. Even though he is one of the script’s least physically-threatening men by comparison, he is also colored by the script’s revelations about men on the whole. In both iterations, Joe is the villain of the story as much as he is the love interest. By the end of the real film, even though his destructive act comes to fruition, he is humanized by his love and admiration for Kathleen and everything she represents. Kathleen finds good in Joe, and so the film finds good in Joe, even though, in a way, he does end Kathleen’s life.

But in the script, Joe is accused of being a killer—by the children he loves. He has an aunt (his grandfather’s daughter) and a brother (his father’s son) who are both under the age of ten. In the beginning of the film, he takes them to the Shop Around the Corner for storytime and to buy books. They listen to Kathleen read from a Roald Dahl book. They adore her. And after the Shop Around the Corner shutters for good, the children are livid. “She’s gone forever,” little Anabel shrieks. “And now we’ll never get another book from her as long as we ever live.” “You killed the Storybook Lady,” she adds, as she and Matt burst into tears.

Just as the script emphasizes that most men represent the potential for violence, the script insists on holding Joe accountable for his acts of destruction to the fabric of the homey Upper West Side as well as to the literary world. Here, he must confront his own brutality and overcome it, somehow.

In the film, though, the script’s pervasive themes of male violence and ruination are virtually eliminated. Joe is not represented as part of the eternal, existential threat to women. He’s represented as part of the neighborhood, someone whose love for its goodness makes up for his dismantling of it. He does try to make it up to Kathleen, that he has put her out of business. He helps her heal. She ultimately accepts her circumstances because now she has the chance to write children’s books, which she realizes she never would have otherwise done. In the final film version, Joe is not a threat to her being, on a fundamental level. He’s just a force of change. Neutralized.

You’ve Got Mail is about the Upper West Side and the book industry, two small, personal worlds that are threatened by the impersonal, automated capitalistic world represented by both Fox Books and the internet itself. But in the film, the sweetness, the local character of the neighborhood persists. Though Kathleen’s business closes by the film’s end, the West Side does cling to its senses of community and familiarity. The film sentimentalizes, essentializes the denizens of the Upper West Side as part of a like-minded collective, a group of fellows bound together by some unseen force. This neighborhood is comfortable, safe. It’s home. The film’s tagline stresses this: “someone you pass on the street might already be the love of your life.”

But the original film script reverberates with the notion that this formula might also go the other way. Just as much, someone you pass on the street might be a killer. Of your business. Or of you.