San Francisco, March 1907

Nora May French was two weeks late. She was twenty-five years old and had never been late—not without a reason. She knew she was pregnant again. This time, she would need to act quickly; she could not afford a “therapeutic” abortion in a hospital even if she could convince a doctor to give her one. She would have to do this on her own.

She bought the pills on Friday night, easy to secure even though it had been not quite a year since the earthquake of 1906 leveled most of San Francisco. Her local drugstore boasted an array of cheerfully colored boxes on its shelves, advertised cannily as bringing on “suppressed menstruation,” “regulation,” or “the cure”: Dr. Conte’s Female Pills, Chichester’s English Pennyroyal Pills, and Dr. Trousseau’s Celebrated Female Cure. Chichester’s, sold in small metallic boxes of red and gold, were advertised in the newspapers as safe, devoid of dangerous substances, and “always reliable.”

She knew—everyone knew—these compounds were not only unreliable, they were far from safe, containing undeclared noxious chemicals like turpentine. Even their advertised ingredients, tansy and pennyroyal, could kill a woman. Pennyroyal, a form of mint, could bring on the desired abdominal pains but could also deliver cardiovascular collapse, liver failure, and death. Tansy, with its deceptively benign yellow bloom, could induce convulsions and shortly dispatch her along with her fetus.

Nora paid for the pills, buried them deep in her bag, and walked back to her house. Her address, at 415 Lombard Street, was as good a one as any to have if your life was in shambles. Telegraph Hill shook regularly from blasts from the quarry on its eastern slope. She and her neighbors experienced unusual weather: a rain of rocks one day, a haze of smoke the next. Residents had complained, charging the quarry waving bats and brooms, and had even brought lawsuits against the owners, but to no avail. The city, needing boulders to rebuild the seawall, looked the other way, even as entire houses toppled. Nora had now grown accustomed to being covered in dust by the time she reached her door. Mingled in with that dust were the ashes of those who had died in the great fire that followed the earthquake. Though she tried not to think about it, Nora could sometimes feel herself breathing in death with every step.

She got to her home and kicked off her shoes once she was inside the door. She loved this house. Her boyfriend, Harry, had constructed it from the quake’s wreckage to lure her from Los Angeles to San Francisco. They were both poets who needed very little in the way of creature comforts to live. Together they decided there would be nothing artificial about this house. No wood would be painted or finished. It would be as close to nature as one could get in a city. They had been passionately in love with each other and with life then. She wasn’t sure where she stood with him now.

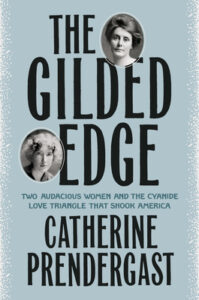

The poet, Nora May French.

The poet, Nora May French.

She saw that a letter from Harry had arrived that morning. Nora looked around to make sure her sister, Helen, was not at home before she opened it. Helen had grown to hate Harry. Months before, Nora had implored her sister to leave a well-paid clerical job in Los Angeles and move north with her. Although Nora and Helen had weathered every step of their childhood of sorrows together, at first Helen flatly refused. How would moving to an earthquake-ravaged city to join its merry band of Bohemians and poets improve their lives? Because, Nora had responded, San Francisco was the seat of the cultural West, not a backwater farm town like Los Angeles. Harry was an editor of a literary journal and knew everybody. And all she had ever wanted to do was write. She needed to write.

So in September of 1906, Nora gathered up her few possessions, put on one of her rare suits without holes, and caught her train. She secured a room in a boardinghouse at 886 Chestnut Street on Russian Hill, not far from where the poet Ina Coolbrith lived and hosted her famous salons of Bay Area writers. But Nora had barely had time to unpack and explore her surroundings when she developed a cold that went straight to her chest. She wound up in Mount Zion Hospital for two days before being released by a condescending doctor who gave her a lecture about going out too much in the evenings.

Helen had immediately blamed San Francisco’s clammy climate for Nora’s ill health and used it as an excuse to delay joining her. More months passed. In the meantime, Nora had won The San Francisco Call’s contest for a poem celebrating the new year and had been featured on a full broadsheet of the city’s paper. She had a new publication almost every month in literary journals. She was accomplishing what she had come to San Francisco to do. And yet she realized she could not live without her sister another day. When by mid-January her sister had still not arrived, Nora boarded a train for Los Angeles, determined to drag Helen back north with her—by the hair and shrieking if necessary.

It hadn’t come to that. Helen, no longer able to keep living without Nora, admitted defeat and joined her. But as much as creative, wild Nora loved chaotic San Francisco, calm, practical Helen hated it. And she had seen far too much of Harry’s harsh words toward Nora and was beginning to worry about her sister. If Helen discovered Nora had gotten pregnant by him, she would pack her bags. The French sisters were the grandnieces of the great Henry Wells, who founded Wells Fargo and American Express, and on the other side of their family, they were granddaughters of the ninth governor of Illinois. They had their families’ reputations to uphold. Nora’s disgrace would be a stain on them all.

Her parcel of pills still unopened, Nora sat in the kitchen and read the letter from Harry. It was everything she had hoped it would be, sweet and passionate. She felt her will, so resolute earlier that evening, begin to falter. She tried to imagine a life with Harry and a child: Harry, walking their unfinished floor at 3:00 a.m., rocking their baby to sleep in his arms as she dozed. A beautiful baby perhaps with Harry’s dark wavy hair but her own spooky eyes. She and Harry could be like Dante and Elizabeth Rossetti, living for beauty and art, while their child rambled happily around the house.

It didn’t take long for this fantasy to collapse. Harry Lafler was still a married man, and despite his promises, Nora did not believe his separation from his wife would ever progress to divorce. In truth, she wasn’t even sure if she wanted it to. She and Harry were bound by passion and recklessness, not responsibility and reality. She was his carefree muse, something ethereal and magical, not an ordinary woman who could get in ordinary trouble. He would recoil from the sight of a swollen belly and bolt from the rigors of fatherhood. She would be left raising a baby on her own—a complete disaster. Even if in 1907 women worked outside the home, rode bicycles, and published poetry, nobody looked favorably on an unwed mother and her bastard. Her child would be seen not as the product of love but rather as the punishment for sin.

She swallowed the pills on Saturday morning. Waiting for the cramps, she distracted herself by sweeping the floors and washing the dishes. After a flurry of activity, she still felt nothing. She tried to will a contraction, but her body showed no interest in complying. Her mind searched for a metaphor for her situation: She was like a rider astride a horse, fiercely spurring it to gallop while it refused to move to any impulse but its own.

Finally, early Sunday morning, a contraction deep in her lower abdomen woke her from sleep. Spasms soon came in waves. Nausea followed. As the pain intensified, she felt like screaming but clenched her teeth—she didn’t want to alarm the neighbors— and let out a low moan.

So this is what it feels like, she thought. It was time to tell him.

Between contractions she went to her desk and took out a piece of Bohemian Club stationery she had filched from Harry (he belonged to one of the more exclusive businessmen’s clubs in San Francisco). Returning to the commode, she placed it on a book balanced on her knee and began to write.

“Very dear,” Nora wrote, “I have been through deep waters, and proved myself cowardly after all.” She was never late, she explained, so she had gone to the druggist. His sweet letter had made her pause, she admitted, but in the end, she did not see another way. “I have gone through every shade of emotion. . . . It was as if we were walking together and my feet were struggling with some pulling quicksand under the grass. I would come near screaming very often.”

A contraction interrupted her writing. She tried to moan only softly in case Helen, who was waking up, heard her. Too late. Helen was knocking at the door. She yelled back to Helen that she was just having one of her moods and desired only peace. It was a ready and believable excuse: Helen knew her sister’s emotional turmoil all too well.

Nora continued writing. “Motherhood! What an unspeakably huge thing for all my fluttering butterflies to drown in! A still pool, holding the sky.” The cramps increased. Her hands shook, but she continued the letter, her script uneven as she worked to steady the pencil. “I looked into it day after day, and sometimes I could see the sky, and sometimes only my drowned butterflies. Oh—”

* * *

Oh. Oh, what?

I’m sitting at one of the broad tables in the manuscripts room of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, turning over Nora May French’s letter, looking for a continuation, but there is none. Nora’s letter ends mid-sentence. I have no idea what Nora wrote next, nor do I know what Harry had to say for himself, if anything.

There must be another page that fell astray, I think, rifling through the file, but nothing related is there. I search through more files of correspondence. Nothing to be found anywhere in the collection—which, I am annoyed to note, is named not after Nora May French but after her feckless boyfriend, Henry Anderson Lafler. Despite having been nationally known in her day for her poetry, her beauty, and her shocking death at the age of twenty-six, Nora May French doesn’t have archives devoted to her papers under her own name. Lafler does—even though his main publications consist of an edited collection of Nora’s poems (published after her death and against her family’s wishes) and a real estate brochure showcasing residential lots in Alameda County.

Allow me to correct the record. It was Nora, not Harry, who was the sensation in her time. Less than a year after she wrote her letter about her abortion, French died from cyanide poisoning at the home of George and Carrie Sterling, whose bungalow was the center of the writing colony at Carmel‑by‑the-Sea on the Monterey Peninsula. Founded in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Carmel colony would become famous for hosting Jack London, Upton Sinclair, and Sinclair Lewis. The death of Nora May French—a beautiful, talented young poet of then national reputation—at the colony’s height would make the news from Los Angeles, Chicago, St. Louis, and Boston to the Twice‑a‑Week Plain Dealer of Cresco, Iowa. Tabloid-style headlines such as “Midnight Lure of Death Leads Poetess to the Grave” and “Girl Writer Tires of Life” capped articles puzzling over the reasons why Nora, who left no note, might have killed herself.

After her death, it was said her friends in her Bohemian literary circle formed a suicide pact, some even carrying vials of cyanide on their person so as to dispatch themselves the moment the thrill of life had faded. Think of it as similar to 1960s California, a more recent period of youthful sexual experimentation, which devolved into violence (the lurid Sharon Tate murder). At the center of the Carmel group was a love triangle in which all three members— Nora and her Carmel hosts, George and Carrie—died of cyanide poisoning. If that weren’t morbid enough, a number of their friends also came to grisly ends, including one through decapitation and another via self-defenestration. Random strangers in New York died with Nora’s poems in their pocket or under their pillow. Historically, Nora has been blamed as the pebble that started these ripples of death. With movie star eyes even before there were movie stars, Nora became history’s most literary femme fatale, her most heralded legacy not poems but corpses.

When I first learned about these bizarre events, I felt drawn to Nora almost immediately. It takes some kind of woman to write a letter about an abortion to her boyfriend while she’s administering it. But I soon became equally fascinated with the woman in whose arms she died, the hostess of the Carmel writing colony, Carrie Sterling. Carrie was born a go‑getter. She left her mother’s boardinghouse for a secretarial job in a Bay Area realty firm, becoming one of the first women in the West to work in an office instead of in a factory or a home. There she met George Sterling, a handsome young man whose connections within San Francisco’s cultural, business, and political elite were surpassed only by his pedigree: A Yankee blueblood whose ancestors had founded several of the East Coast’s early settlements. Riding his uncle’s coattails, George was becoming rich selling East Bay realty, but he lived a double life as the “King of Bohemia,” the head of a group of writers and artists who met regularly at an Italian restaurant on the fringe of the red-light district, reading poetry aloud and sketching the clientele till the wee hours. This group would soon move to Carmel, where Carrie would find herself tasked with feeding them nightly in her own house—hardly the life she had imagined for herself when she married George.

The popular legend of Carmel has it that George Sterling and his friends stumbled upon a landscape of unparalleled beauty, poked around for a few days, and decided that only there could they make great art. In truth, George was a seasoned land developer being cut in on an unusual deal: He had been hired by the Carmel Development Company as their resident Bohemian to lure his artistic friends down to Carmel, creating buzz about what was then only a square mile of nearly barren dirt next to a bay. Carmel thus became the first town to consciously use artists as the leading edge of gentrification of California’s new frontier. The Sterlings were forerunners of what we call “influencers” today. Their jobs were to be seen and be written about.

And they certainly made Carmel seem like a lot of fun at first. The town captured the nation’s attention as a place where women and men spent their evenings in literary salons discussing poetry and philosophy before heading down to the beach for bonfires and swilling beer from tomato cans. Despite the appearance of gender equity, behind the scenes, Carmel was a roiling pot of exploitation. Women’s horizons were limited by the identities the men assigned them, namely scorned wife and elusive muse. Carrie was obliged to host her husband’s endless guests while he ran around sleeping with the most attractive of them. “He bays in iambic pentameter,” Jack London once remarked admiringly of his best friend Sterling’s womanizing.

Let’s be clear: Carmel is just as much Carrie’s legacy as it is George’s—it would not have happened without her labor—but with the exception of a “thanks to my wife for typing” form of acknowledgment, she got none of the credit. Meanwhile, Nora May French, whose reputation was used to bolster the colony’s image, was passed along a line of Bohemian men who treated her as a perpetual ingenue, co‑opting her talent in an attempt to claim her as their personal discovery; they plied her with unwanted editorial advice while maneuvering her toward the bedroom.

Neither Carrie nor Nora went to Carmel anticipating such poor treatment. Quite to the contrary: Both women had every right to expect that life for them would be better than it had been for their mothers. They were both New Women, a name for women on the trailing edge of the Gilded Age who sought to enjoy the spoils of economic expansion. Factories needed their cheap labor. Magazines, then proliferating, needed their image. Novels of their day captured their experience through new heroines: the gambling Lily Bart of The House of Mirth, the lovestruck Edna Pontellier of The Awakening, the fallen Tess of Tess of the D’Urbervilles. These novels dangled the possibility of fulfilling lives outside the bounds of marriage and children before doling out hefty punishments for women who dared to dream. Carrie’s and Nora’s real lives followed these plots, illuminating all the dilemmas of turn‑of‑the-century womanhood. Treated as mere accessories to male ambition, Carrie and Nora were set on a crash course against each other, one that resulted in their mutual destruction.

Considering this history, I began to wonder about the term “New Woman,” so in vogue at the time, so evocative of freedom and limitless possibility. When in history, really, are women not “new”? When are they not enjoined to remold themselves to a world that has never bothered to change much for them? The truth is that when New Women emerged at the edge of the Gilded Age, there were no “New Men” to greet them. The phrase “New Men” didn’t even exist—that’s how entirely not “new” men were. As a result, despite all the progress on the labor or political front, the relationships between the genders remained largely unchanged. Women could strive to be suffragettes, Bohemians, or Gibson Girls (named after the glamorous but independent women sketched by popular illustrator Charles Gibson), but to men they were still only potential conquests or crones, a Madonna–whore complex on a national scale. Even when men claimed to want women who were more sexually liberated or allowed to work outside the home, all the negative consequences of the flowering of liberation were women’s alone to bear.

I look back at Nora’s letter with this in mind. As I hold it in my hands, I’m aware that it is one of very few early-twentieth- century first-person accounts of abortion, and it won’t be around forever. It is already over one hundred years old. Wouldn’t it be nice, I think, to see it amid a collection of other letters testifying to the length of women’s struggle for reproductive freedom, rather than among the papers of an abusive ex‑boyfriend?

But that’s not the way archives generally work. Unlike libraries, archives are organized by the life of a person or organization, not by subject. Someone decided that Harry Lafler’s life was significant, so his papers were preserved. I realize how lucky I am to be holding Nora’s letter at all, considering its unlikely journey. It had traveled from her hands to Lafler’s, subsequently landing in the closet of a friend or family member before being traded through collectors, to arrive in the 1950s at the marbled wing of the Bancroft Library at the center of Berkeley’s campus, just ten miles as the crow flies from the Telegraph Hill flat where Nora, in agony, wrote it.

That particular flight path made Harry Lafler the de facto protagonist of his and Nora’s joint history. But I want to push back on the archival logic that has elevated Lafler and many of his literary male compatriots beyond their rightful place in history. I was often asked in the latter stages of this project, Why are you writing about unknown women? This question rattled around in my head as I looked at Carrie’s and Nora’s faces splayed out on the front pages of century-old newspapers, as I read article after article that breathlessly followed their lives, their deeds, and their deaths. Neither of them was unknown at the time they lived.

Yet in the archives, I encountered a trail to their lives that had been deliberately wrecked. Letters written by them or about them had the top or bottom ripped off. Names or other incriminating information had been scratched out with pen and rendered illegible. Or—in the case of Nora’s letter to Harry—pages had been deliberately held back. Carrie and Nora were not buried in the archives because they were dull women whose lives were of no consequence. They were buried because their personal histories exposed events and insights far too revealing of the flaws of the men who surrounded them.

Archives can resemble graveyards, with marked tombs for men that also contain the scattered bones of various women. You have to do a lot of searching to reconstruct women’s lives. I traveled from New York to California to small towns in the interior of the country to find the documents that would connect the dots of Nora’s and Carrie’s stories. I found through these artifacts a very different story than the idyllic tales of Bohemian California featuring altruistic patrons and open-minded, progressive men. In this book, I take you with me as I read against the grain of archives, resisting the protagonists that the file headings offer, and instead look for the silences that have been carefully constructed around women. What I learned ultimately about Carrie and Nora is true of all women, potentially: One doesn’t die but becomes an unknown woman, one mutilated sheet of paper at a time. I offer here a story within a story—on the one hand, the tale of the remarkable women in a Bohemian experiment that ended in disaster; on the other, the concerted efforts to make sure you would never hear about it.

___________________________________