Am I a murderer?

Many Republican lawmakers would claim that I am. Since the U. S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, already 18 states have criminalized abortion and elected leaders in over half the states are attempting to do so. “Personhood” laws in Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas make an embryo eligible for child support and tax credits. Many in our government acknowledge no distinction between a human toddler and fetal matter, attached by an umbilical cord to someone else’s uterus. Abortion, these lawmakers insist, is homicide.

In the spring of 2010, I had an abortion eight weeks into an unwanted pregnancy. I was a healthy 25-year-old student working on my Ph.D. dissertation, with secure housing and plenty of financial support. I knew I wanted to become a parent eventually. And I knew, as clearly as I’d ever known anything, that I didn’t want to continue that pregnancy.

About one in four American women has had an abortion. Most of us have family members, friends, and doctors who helped us make that decision, drove us to appointments, and provided care. Fetal “personhood” laws make all of us murderers and accessories to murder. In this country, we punish convicted murderers. We put them in cages, locked away from their loved ones, ostensibly to deter other would-be murderers and protect the rest of us. Most states where abortion is a crime currently uphold the death penalty. Indeed, last year in Texas, five male lawmakers authored a bill that would have made getting an abortion punishable by death.

Should the government punish this enormous portion of our population? If so, to what end? Certainly not for the sake of community safety; abortion access is directly linked to a decrease in crime rates. Abortion-havers and abortion-seekers pose no threat to any other citizen’s existence.

Whose existence, then, is at stake when we dare to claim our reproductive power, to prioritize our educational and creative goals, to plan our families, to make health-related and economic decisions for ourselves? What do we threaten?

The answer could have been written by James Carville, if he’d been a feminist advising Hillary’s campaign instead of Bill’s: It’s the patriarchy, Stupid.

Patriarchal norms have long dictated what counts as homicide and how to punish offenders in this country. In colonial New England, an old British statute declaring all husbands to be “natural lords” over their wives meant that a woman who killed her husband was guilty of “treason” against the state. Many convicted women were burned to death rather than hanged based on this technicality. For much of this country’s history, an enslaved woman who self-managed an abortion was guilty, by law, of destroying someone else’s future “property.”

Abortion is freedom. Without authority over our own internal organs, we become the property of the state the moment we become pregnant. Reproductive Justice means our bodies belong to us, and it depends on abortion access for all.

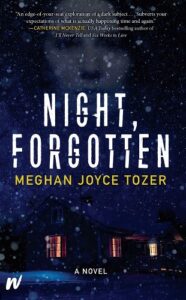

The fates of people who become parents against their will is a main theme in my novel, NIGHT, FORGOTTEN. My protagonist Julie marries a man whose Catholic mother-in-law believes abortion is murder and works for a so-called “crisis pregnancy center,” where she impersonates a medical professional and lies to people who are already scared and confused. This behavior is alarmingly typical at the over 2,530 real-life fake clinics around the country, many of which receive federal funds.

For me, the choice to have an abortion and the procedure itself were both straightforward. Other people face hurdles at every step, depending on their age, race, class, where they live, and the type of support they receive. In my research for NIGHT FORGOTTEN, I learned just how complicated the decision can be. My protagonist Julie was the victim of a rape that resulted in pregnancy, but she’s unable to prove the crime. Many anti-abortion advocates hold up “rape exceptions” as a compromise, without acknowledging the societal and bureaucratic barriers that prevent the vast majority of rapes from ever being prosecuted. The very concept of a rape exception implies a false dichotomy between victims of sexual violence who earn an “exception” to forced parenthood through their suffering, and women who deserve to be punished for enjoying non-procreative sex.

After the abortion, I finished my dissertation and founded a non-profit to help at-risk girls. I met the man who would become my husband, with whom I’m now raising two lovely children. I’m grateful for the circumstances that allowed me to build the family and life of my dreams, but those circumstances should not be rare. Abortion itself should not be “rare,” necessarily, given the frequency of unwanted pregnancies combined with the enormous health risks of giving birth.

Nearly two-thirds of people who get abortions in this country are already mothers with existing children to care for. Most are living in poverty. About a quarter identify as Catholic; some even return to the same clinic the next day to protest other people’s access to abortion. That last group might be hypocrites, but they are not murderers.

None of us is.

***