My first newspaper job out of college was in Little Rock, Arkansas. I was hired as a general assignment reporter, meaning I covered everything from business news to county fairs. Mostly I wrote fun stories, nothing too heavy. And then, one day, the paper’s old crime reporter quit. An editor took me aside and told me the beat was now mine. Murders. Robberies. Car crashes. Fires. This would be my world.

The guy who preceded me in the job, an old newshound named Jim, gave me a bit of parting advice.

“Anyone who sticks in this job for long enough becomes one of three things,” Jim said. “A cynic. An alcoholic. Or a reformer.”

My new daily schedule was this: Wake up. Go to the office. Call the coroner to see if anyone had been murdered overnight, a story to begin to work. Then turn on the police scanner and wait for new mayhem.

When a call came over the radio, I quickly realized that I was hearing about incidents at the same time as the police. So, when I ran to my car and raced to crime scenes, sometimes I arrived as violence was still unfolding. One day, I hurried to a Popeyes, where there had been a report of a shooting. The cops hadn’t arrived. There was one man sitting on a curb in the parking lot. I asked if he’d seen what happened. “Oh, hell yeah,” he said. It was then I saw the blood running down from a gaping wound on the man’s leg.

That was one of the easier days. I saw bodies maimed. The dead lying in pools of blood. I saw relatives screaming in grief. And I forced myself to approach them. To ask in that moment for a quote for my story. I was just doing my job.

As I came to find out, Little Rock was a violent city, with gangs so fierce in the 1990s they’d been featured in an HBO documentary. But I also discovered that the cycles of violence stretched back much farther.

There were the stories of police shootouts with organized criminals in the streets. Stories of racial violence so extreme and ugly they hurt the soul to even tell. Because Little Rock was a frontline in the war of racists and the Klan against African-Americans. A city that started as a frontier outpost and never quite left that wildness and lawlessness behind.

One story stuck with me. It was by chance that I learned of it. An incident from the mid 1940s. On New Year’s Day, two police officers went off into the woods. Hunters heard shots fired, then found bodies on the ground. To say more than this would be to reveal the end of the story, but it was a crime that was horrifically shocking at the time, one with a long trail of violence stretching across the city, touching politicians, journalists, mobs and militias. And discovering it in the present, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. In quiet hours, I found myself going down to the newspaper’s archives, sorting through the stacks, scouring microfiche for stories about the crime and the details and characters around it.

As I read, I saw that this crime’s tendrils spread into everything. Into the horrors of racial violence and segregation. Into organized crime.As I read, I saw that this crime’s tendrils spread into everything. Into the horrors of racial violence and segregation. Into organized crime. And, above all, into the failures of the police. It isn’t a story about corruption in the institutional sense. There were no cops on the take. It was a story about police who fall to corruption of another kind. Corruption of the soul.

At the center of it all was the head of Little Rock’s police at the time, a man who saw demons encircling his city—literally. But it wasn’t the schizophrenia that ruined him. It was his choice to pursue his goals with whatever force he could muster. To enlist violence in the name of peace. To meet imagined demons with brutality.

* * *

A couple of years later, my wife and I decided to move, and I left the crime beat behind. Better than to become an alcoholic or a cynic, I thought. And I didn’t feel like I had it in me to be a reformer.

As we moved to our new home, I brought that research with me. Copies of files and old articles. I kept returning to them. This was a story, one I felt I had to tell. At the same time, I began to write comic books and graphic novels, and I decided this story needed to be told in that medium. A noir comic inspired by true events.

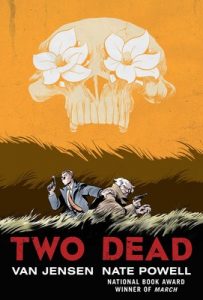

Later, I teamed with Nate Powell, artist of the National Book Award-winning March trilogy, to complete the book. I couldn’t imagine it in any other artist’s hands. Nate is a phenomenal talent who covers the page with rich, dark ink, painting with shadows. He’s also a native of North Little Rock. He knows the region and its ghosts as well as anyone.

As we worked, our book—Two Dead—took on the mantle and trappings of noir. Part of it was the time period; imagine L.A. Confidential but set in the southeast. Most of it was the story itself. Hardened cops. Deep mysteries. Double crosses. Shadowy meetings with informants. Justice meted out with a gun.

Our work on the book began around 2013 in earnest. And then, in real time before our eyes, this seventy-year-old crime that served as the basis of our story became ever more relevant. Michael Brown. Eric Garner. Philando Castille. Seemingly countless others.

Young black men whose lives were ended at the hands of police. As the #blacklivesmatter movement grew, Nate and I understood: This is what our book is about. The way that the power of police, when corrupted, destroys lives.

I saw it firsthand, back in my newspaper days. One day, a cop took me on a ride along. He showed me how he’d tailgate African-American men, growing more aggressive until they committed some minor infraction. Then he would pull them over and search their vehicle, unless they knew they could refuse. To that cop, this was just how the job is done.

Two Dead—published last year by Gallery 13—is set long ago, but it shows above all else how little has changed. Violence, perpetuating.

And that’s the thing I found myself thinking about the most, considering where our book fits into the tradition of noir. Now, I love crime fiction. But these stories so consistently show the power of violence. Violence as solution. Violence as the vehicle of justice. The hard-boiled detective, shooting dead the villain.

But this, I think, is false. Violence is never final. It lingers in the grief of the victims. It returns in the form of revenge. It destroys even the aggressors. It leaves no hands clean.

And so while I hope that our book is a good, tense read, I know that it criticizes noir as much as it celebrates it.

I don’t know. Maybe I became a reformer after all.