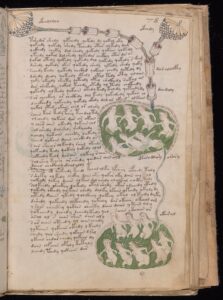

The most famous cryptic manuscript of the medieval period is—as far as we know—written in a unique language that to this day remains understood only by its author. It was found in 1912 by a Polish rare book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich, hidden among a pile of manuscripts in the Villa Mondragone, Italy. Voynich was immediately captivated by its unknown language and the strange illustrations of mostly non-existent plants and groups of nude bathers, and purchased it along with twenty-nine other items. (During more than thirty years Voynich sold the British Museum more than 3,800 books, many of which were so unusual that they were given their own ‘Voynich’ shelf mark.)

The cryptic text now known as the Voynich Manuscript has since been the obsessive focus of study around the world, and as yet none of the professional and amateur cryptographers—including American and British codebreakers of both World War I and World War II—has been able to crack it. Perhaps this is because it exhibits characteristics of both a complete, natural language and a complicated designed cipher, with letter-shapes tantalisingly similar to known shorthand symbols. It doesn’t follow the structural rules of the contemporary Renaissance polyalphabetic ciphers, yet it does show clear signs of having its own internal structure. And this, really, is its eternal attraction, the sense that the key to unlocking its secrets is within reach; that with enough patience and the right approach anyone, linguist or layman, can break it. Of course, this is assuming it’s not a sophisticated hoax, which is an entirely possible explanation. Over the years, the language of the Voynich Manuscript has been claimed confidently to be seventh-century Welsh/Old Cornish; an early German language; the Manchu language of the Qing dynasty (1636–1911) of China; and Hebrew enciphered by Roger Bacon, describing alien technology of the future for generating DNA with sound. Perhaps it’s the Nahuatl language of the Aztec written by Francisco Hernández de Toledo (1514–87), naturalist and court physician to the King of Spain; or it could be the language of the angels, linked to John Dee’s Book of Enoch, with the illustrations of unknown plants perhaps being the original species found in the Garden of Eden. It’s a recipe book; a diary; a guide to viewing galaxies using telescopes (by Roger Bacon again); a nonsense stage prop made by Francis Bacon; an early work by Leonardo da Vinci; a record of speaking in tongues; outsider art; and so on. Wilfrid Voynich, incidentally, referred to it with true dealer’s aplomb as ‘The Roger Bacon Manuscript’, and held the unfounded belief that John Dee had sold it to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (1552–1612).

So what exactly do we know about the possibly celestial, possibly nonsensical manuscript? In 2009, its vellum pages were radiocarbon-dated to between 1404 and 1438 with 95 per cent certainty, although there is no way yet to prove that its writing was added at this time. The smooth unhesitating handwriting of its right-handed author has been described as reminiscent of the Italian Quattrocento style of c.1400–1500. The spelling of some marginalia in the zodiac section suggests that the manuscript was at one time in south-west France, and the handwriting of two other owners/readers suggest it was likely already written before 1500. To add to the challenge, the evidence suggests that the pages were originally arranged in a different order, and that the written numbers of both the folios and quires were added later. By 1969, the manuscript was in the possession of the dealer Hans P. Kraus, who donated it to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Today, with endless patience, the librarians politely accommodate an unending flood of examination requests from enthusiasts around the world. Every year there is a new claim to having successfully unlocked its secret that ultimately proves unfounded. If indeed the Voynich Manuscript does have a story to tell, its secrets—alien, angelic or otherwise—remain its own for now.

Cryptic writing using a confusing medley of language and symbols, usually more distinguishable than that of the Voynich Manuscript, remained a popular feature of occult works for centuries, a literary equivalent of speaking in tongues.

_________________________