One of my favorite things, as an author, is to play with structure. My home genre is science fiction because it allows me to tip the natural world to the side to expose the interconnected tissue. But I also have a deep love for mystery as well. I love the twists and reveals. It turns out that these two genres play really well together.

I think that genres divide into two major types: structure-driven genres and aesthetic-driven genres. Structure-driven genres are things like mysteries, thrillers, and romances. Without a meet/cute and happily ever after, it’s not really a romance. Without red herrings and unveiling the murderer, it’s not a murder mystery.

Science fiction and fantasy, on the other hand, are driven by the aesthetic. They are about the look and feel. The sense of wonder. They don’t have an inherent plot structure.

This means that you can map Science Fiction onto a Mystery structure easily.

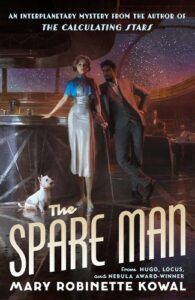

When I decided I wanted to do “The Thin Man in space,” I needed to understand the structure of the Nick and Nora movies specifically. So I began by watching all six of the films. This was a great hardship, as I’m sure you can imagine. Here are some of the beats that are in all of the films: A happily married couple and their small dog solve crime while engaging in banter and drinking too much. Interestingly, they also contain the element that Nick does not want to investigate and Nora really wants him to. Nick almost always gets along well with law enforcement. He has an uneasy relationship with the wealth of Nora’s family. There’s always a scene in which he goes off sleuthing on his own and carefully looks over a crime scene. More than one murder.

From there, I started building the world of the novel. THAT is the hallmark of science-fiction and fantasy. We engage in worldbuilding in which we think about how changing an element or introducing a technology has ripple effects. For this, I knew I wanted to be on a cruise ship in space. There’s a writing workshop that my podcast, Writing Excuses, runs every year on a cruise ship. I based my ship, the ISS Lindgren on the types of things that happen on those and extrapolated for the future.

3D printers exist now and pushing them forward 50 years gives us matter printers and printed clothing. Chronic pain would be managed by a Deep Brain Pain Suppressor. Constant connectivity transforms into new etiquette about privacy.

That gave me my setting and my structure.

Next, we have the characters. I wanted them to be as much like Nick and Nora as possible while also being their own people. So I turned to one of my other favorite tools — inversion. I really enjoy taking a piece of a story and turning it into its opposite. In the films, Nick is the detective and Nora is the spouse who wants to participate in sleuthing but isn’t allowed.

Sure, I could have gender-swapped the characters, but that still means the detective is doing the detecting. I’m more interested in stories in which a competent person is put in a situation where their competencies are irrelevant. That means that my Nora — Tesla Crane — is still an heiress. Her Nick — Shalmaneser Steward — is still a retired detective. My Asta — Gimlet — is still a dog.

But let’s invert some things. Shal is placed in a position where he can’t investigate, even though he’s a detective because he’s arrested as a suspect. Tesla has to investigate, but I strip her of her power — money — by having security cut off access to her accounts.

And in my novel, Gimlet, the most perfect of dogs is a service dog, so she has self-awareness and discipline that her inspiration lacks.

Then there are the suspects. A hallmark of murder mysteries is the existence of multiple suspects all of whom have motives, opportunities, and secrets. Setting this in the future doesn’t change the need for those; all it changes are the kinds of occupations they have and the ways in which murder can be committed.

Again, because a hallmark of SF is worldbuilding, I looked to science for methods that could only exist in the environment I created. In SF some of the major questions you ask when doing worldbuilding are Why, How, and With What Effect. “Why” is the past. “How” is the present. “With what effect” is the future or the ripple effects.

Warning: the next paragraph is spoilery about a murder.

For instance: Why… The spaceship needs to reduce the amount of material they bring on board. How… They reduce material by using closed-loop recycling and matter printers so that the overall mass on the ship remains close to the same. With what effect… Closed-loop recycling breaks down any solid matter into a slurry that is then stripped into component parts and reused. Put a human body into there, and it’s much better than burying a body in cement.

You can apply the same tools to any element of the original films, often by taking a “how” and switching the “why” to get a different “with what effect.”

For instance: In the original film, Nora is an heiress. Why: Her father was in sawmills. How: She’s very wealthy now. With what effect: She can do whatever she likes.

My main character, Tesla Crane is also an heiress, but let’s switch the “why.” Why: Her father was an inventor with Elon Musk levels of fame. How: She’s an heiress, yes, and also a famous inventor. With what effect: Her wealth means that she can afford to do anything but can’t go anywhere without being recognized.

That in itself is an inversion because Nick is well-known within the world of the films and Nora is not. My goal is to wind up with something that has the glittering banter and twists of The Thin Man movies with the gee-whiz factor of an interplanetary cruise liner.

Nick and Nora in space. The same, but different.

***