An assassination. A hanging. An axe murder.

How much of the way I tackle these topics in YA true crime caters to teens themselves, and how much is presenting ugly realities in such a way that adults (aka: gatekeepers) won’t balk at handing these books to a kid? In the current political climate, that’s a very big question.

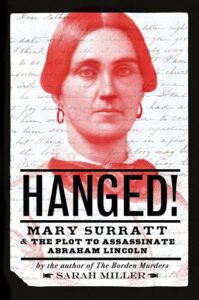

Hanged! Mary Surratt and the Plot to Assassinate Abraham Lincoln and The Borden Murders make almost no concessions to gatekeepers — especially the current breed. I agree with Laurie Halse Anderson’s assessment that the folks who are bent on censoring books are mostly concerned with “protecting” kids from conversations adults don’t want to have. Here’s an example that suggests Anderson is correct: the teacher who changed their mind about using The Borden Murders in the classroom due to a mention of Lizzie’s bloodied menstrual cloths. A double axe murder is no problem, but menstruation is a deal-breaker? In situations like that, I’m 100% ok with making grown-ups squirm a little.

For the most part, though, once you’ve gotten past the gatekeeper hurdle, writing for a young adult audience is not terribly different from writing for adults. Teens might need a little more historical context here and there, but in a society where Google is at nearly everyone’s fingertips, even that isn’t as pressing a need as it used to be. That said, here are four things I do keep in mind when writing YA true crime:

Let the horror be implicit

How about the matter of plain old gore? That’s the first thing folks are inclined to wince over when they realize I’m chronicling murder for teens. With stories like these, it’s inevitable. When someone is shot point blank or bludgeoned to death, there’s no neat way around it. My policy is to describe the scene as it is — no more, no less. Gore (or violence or sex) solely for the sake of shock value has no place in literature for the under-18 set.

Shift the focus

I’m not in the business of delving into the criminal mind, or of solving cold cases. Despite the verdicts, Mary Surratt’s and Lizzie Borden’s roles in the crimes they were accused of remains unknown. The truth is — and probably will forever be — inaccessible. That leaves me with what I like best: the impact of the crime on the community, and in particular how the media and the public’s response to affects the pursuit of justice. This also happens to be the point of greatest potential resonance with teens. There’s a striking parallel between newspaper coverage of the accused in the 1800s, and the way social media skews our perceptions of one another today. The majority of kids know exactly how it feels to be plagued by a rumor, or to have one small facet of their personality pushed under a microscope for public dissection. From there it’s easy to get readers thinking about how issues like sexism, racism, and other biases impact who gets arrested, accused, and tried, and why.

Stay in the moment

Anyone who picks up Hanged! Mary Surratt and the Plot to Assassinate Abraham Lincoln knows what happens to Mary Surratt before they even open the book — it’s right there in the title. The suspense depends entirely on narrowing the reader’s field of vision so that they have access to no more information than anyone else did during the night of April 14, 1865. How did it feel to be in Washington, D.C., that night as the news raced from street to street? We’re so accustomed to the fact of Lincoln’s assassination that it’s easy to overlook how unthinkable the murder of a president was in the nineteenth century. Suspense isn’t solely about what happens in the end — it’s also about how it happens, and the emotional roller-coaster ride in between the first and last chapters.

Streamline

To my way of thinking, the most dangerous poison in YA nonfiction is detail overload. Some folks might raise a skeptical eyebrow to hear me say that. Hanged! and The Borden Murders are admittedly not short on minutiae. The trick is in recognizing which morsels of information fuel curiosity and intrigue, and which tug a reader off the main path of the story. If you’ve ever opened a biography only to find that you have to wade through a chapter (or two or three) on someone’s parents and grandparents before you get down to the person you’re actually interested in, you already have a sense of what I mean. In true crime, paring down the background info on peripheral figures like investigators, lawyers, and judges helps a lot, as does keeping the social and economic history of the community to a minimum.

This is often the hardest part for me. In Hanged! there was a piece of testimony I desperately wanted to cram into the story. Two soldiers swore under oath that they had been walking down H Street on the night of the president’s assassination when a woman thrust her head out of a window and asked them “what was wrong down town.”1 It seemed an odd question, since the clamor over Lincoln’s murder had not yet reached that neighborhood. The soldiers subsequently concluded that the woman must have been Mary Surratt, and further that she must have known about the murder plot — otherwise why would she have been calling out for news before anyone else in that district? However, when Mrs. Frederick Lambert read the men’s testimony in the newspaper, she knew at once that they were wrong. She was the woman who had shouted out her window on the night of April 14, 1865. The soldiers had indeed been walking down H Street, but mistook the Lamberts’ house (no. 587) for Mary Surratt’s home at no. 541, less than two blocks away. Mrs. Lambert promptly alerted the authorities and testified in court to correct the error.

It’s one of the finest examples I’ve ever encountered of how even the most well-intentioned witnesses can be mistaken and/or misled by their own assumptions. The trouble was, that information didn’t come out until 1867, at Mary Surratt’s son’s trial. Including it would have meant doubling back over ground that had already been covered. As much as it pained me, I had to let that detail go. Thankfully articles like these let me resurrect some of the extras I had to part with!

***