“I’ve never played a hero in the cinema.”

– Orson Welles in a Cahiers du Cinema interview

Did anyone ever play a villain as well as Orson Welles?

He was perfect as the charming black marketeer Harry Lime in The Third Man, the clock-obsessed Nazi fugitive Franz Kindler in The Stranger and the corrupt border-town detective Hank Quinlan in Touch of Evil.

But have you seen his performance as the strangest villain of all, the title character in the 1955 crime film Mr. Arkadin?

Most people have not, and until recently that unenlightened group included me. Then, during a one-month trial of a popular streaming service, I spotted Mr. Arkadin among their selections so I queued it up for viewing.

An hour and 45 minutes later, as the credits rolled, my jaw was on the floor. A lot happens in this movie. At one point, Welles dresses up as a crazy-eyed Santa Claus. There’s a scene involving a flea circus—yes, actual fleas. And at a crucial point in the plot, the hero gets into a tug of war with a man with no pants. I loved it!

The cast was chock full of old pros and a couple of newbies, and they all appeared to be enjoying themselves. Some scenes feature funhouse close-ups of grotesque faces. Others provide a vast spectacle, including a Goya-themed masquerade ball in an ancient castle and a march of hundreds of hooded Catholic penitents.

And, as with The Third Man, this movie features a devilish little monologue by Welles. In offering a toast at the ball, he tells a circle of admirers the fable of the scorpion and the frog. Welles didn’t invent the story, as some have suggested, but he appears to be the one who popularized it.

I wanted to know more about this seldom-seen gem, so I typed in a query to Google—and, like the protagonist in Mr. Arkadin, I soon realized I was in way, way over my head.

Some accounts say there are five different versions of Mr. Arkadin (pronounced ar-KAH-din). Others counted seven. There may be eight by now.

The movie, sometimes known as Confidential Report, is based on a novel that Welles wrote—except he said he didn’t write it, even though his name is on the cover. Instead, the book and the movie derive from a screenplay Welles did write—except that maybe the screenplay is based on a radio script, which he may or may not have written.

And I haven’t even mentioned the Soviet spy who was behind it all, or the stolen hotel furniture, or the lingering mystery about the origin of one version of the film.

Confusing? Oh yes. Delving into the backstory of Mr. Arkadin is like wandering into the hall of mirrors at the end of his film The Lady from Shanghai. Finding the exit sign is so frustrating you feel like breaking things.

Director Joe Dante (best known for Gremlns) has a series on YouTube called “Trailers from Hell.” In the entry on Mr. Arkadin, Dante calls it Welles’ “most mysterious movie.” This is an apt description.

“It was the best popular story I ever thought up for a movie,” Welles told fellow director Peter Bogdanovich, “and it should have been a roaring success…It was blown, blown, blown by the cutting.”

* * *

In outline, the plot sounds like a spoof of Welles’ earliest masterpiece, Citizen Kane: An investigator reconstructs the life of a wealthy man, trying to find out his biggest secret.

In Kane, as everyone knows, the secret is the meaning of his last word, “Rosebud.” In Mr. Arkadin, it’s something far more important: How elusive billionaire Gregory Arkadin first acquired his fortune.

In both films, the title character is played by a heavily made-up Welles. In Kane, the subject is dead when the investigation begins. In Mr. Arkadin, he’s very much alive, but claims he can’t remember anything prior to 1927.

But there are differences. Kane begins with a “NO TRESPASSING” sign outside Kane’s Florida estate, Xanadu, and slowly zooms in to show off the main character dropping a snow globe as he dies. Mr. Arkadin—or, at least, the so-called “Corinth version,” which is the one I saw—begins with an unoccupied airplane soaring over Europe on Christmas Day. A voice-over by Welles promises that this is a true story and that the film will explain how the plane came to be empty.

In Kane the investigator is a mild-mannered, faceless newsreel reporter. In Mr. Arkadin, the investigator is Guy Van Stratten, a small-time American smuggler who’s just gotten out of jail. He’s a hustler who thinks he sees a way to glom onto some of Arkadin’s millions.

Van Stratten is aided by his sometime girlfriend, a bubble dancer named Milli, played by English actress Patricia Medina (who later married Welles’ Kane co-star. Joseph Cotton). Their quest begins when they see a man killed by a knife in the back. As he dies in front of them, he gives them a clue to Arkadin’s past.

Van Stratten is played by Robert Arden, a little-known American actor whose experience mostly involved stage and radio work. As an actor his greatest asset was his voice. It reminded me of Howard Duff, who starred in the radio show “Sam Spade, Detective.” Like Duff, Arden always sounds like he’s got a chunk of irony caught in his throat.

Arden’s down-at-the heels character tries to seduce Arkadin’s dark-haired daughter Raina, played by an Italian actress named Paola Mori. Her real name was Contessa di Gerfalco—yes, that’s right, she was a real countess.

During filming of this movie, Mori was involved in a passionate affair with the actor playing her “dad” and wound up becoming Welles’ third (and final) wife. You can deduce the way he felt about her from the fact that he cast her as his leading lady even though her dialogue had to be dubbed by the English actress Billie Whitelaw.

Arkadin is trying to protect his daughter Raina from getting involved with such an unsavory character, so he dispatches his minions to compile a dossier on Van Stratten. But when Arkadin confronts him with the file, Van Stratten isn’t embarrassed. Instead, he scoffs that he could easily compile an equally damaging report on Arkadin.

The billionaire calls his bluff, hiring Van Stratten to dig into his past. Arkadin says his goal is to make sure there’s nothing there that would hurt his chance at getting a big Army contract for building some military bases. He offers Van Stratten $15,000 (a princely sum at the time—today it would be worth nearly $150,000) to find out where he came from and how he first became wealthy.

Van Stratten then hops around the globe on Arkadin’s dime, tracking down clues to his former life by questioning a variety of outrageous characters.

For instance, Sir Michael Redgrave, whose film career began in 1938 with Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, plays a seedy Polish antiques dealer who’s constantly trying to get Van Stratten to buy something he keeps calling a “teleo-scope.”

Then there’s a bowler-hatted Akim Tamiroff—so good as the villainous Joe Grandi in Touch of Evil—as a wheedling ex-con who won’t do what Van Stratten wants until he gets a Christmas goose. (Yes, just like Die Hard, Mr. Arkadin is a Christmas movie.)

Best of all is Katina Paxinou, a Greek actress who won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her debut film, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943). She plays the woman who holds the key to the Arkadin mystery.

These folks have such a grand time hamming it up that while watching them you almost forget about the dark undercurrent running through the narrative—namely the malevolent force that is Arkadin himself.

* * *

“Mr. Arkadin is not Welles’s dark night of the soul,” Lars Trodson, author of the book About Orson, wrote in a blog post on the film. “This is a lark, a jig of a film; it’s a bright little moment under the Spanish sun.”

But that’s not how Welles felt about it—at least, not his own character, whom he describes in very dark terms.

“Arkadin is a profiteer, an opportunist, a genial parasite who nourishes himself on corruption—and who doesn’t look for ways to justify himself,” he told Bogdanovich.

According to Welles biographer Simon Callow, Welles based the character on a real-life munitions salesman, Sir Basil Zaharoff, who had earned the nickname “The Merchant of Death.” Zaharoff was described by a 2012 Smithsonian magazine profile as “a brothel tout, bigamist and arsonist, a benefactor of great universities and an intimate of royalty” who so routinely sold arms to both sides in a conflict that the practice came to bear his name.

Another Arkadin inspiration, according to Callow: arms manufacturer Fritz Mandl, Hedy Lamarr’s first husband. He befriended Mussolini and sold munitions to Hitler, despite his own Jewish heritage. Mandl was so powerful in his native Austria that it was said, “He could break a prime minister faster than he could snap a toothpick in half.”

In Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles: A Biography, she cited a letter from Welles claiming a different inspiration—a pair of millionaires he’d met in Italy, one Latvian, one Hungarian: “One of them loved to buy out all the whores from some nightclub in Rome and bring them up to his villa, and the other…had the biggest expensively bound pornography collection in Europe.”

The rest of it, though—the story of the tough-guy investigator who makes a bad bargain with a wealthy man and falls for the wrong woman—comes straight from Welles’ own lifelong obsession with pulp fiction.

“Welles loved the genre,” Callow explains in his third volume about Welles’ life, One Man Band. “All his life he traveled with a suitcase full of pulp fiction, thrillers, gangster stories, crime stories, which he consumed at a rate of two or three a day. He claimed to have written these kinds of stories for cheap magazines as a teenager in Spain.”

What he loved about them, Callow said, was their narrative drive, their ability to grab readers right from the start and drag them along to the slam-bang finale. An interviewer once asked Welles what was most important to him as a filmmaker, he replied, “Story, story, story.”

But where this particular story came from is, like Arkadin’s own origin, something of a mystery—one that starts with Harry Lime.

* * *

If you haven’t seen The Third Man, first, what’s wrong with you? It’s a great movie! And second, skip this next paragraph because it contains a major plot spoiler.

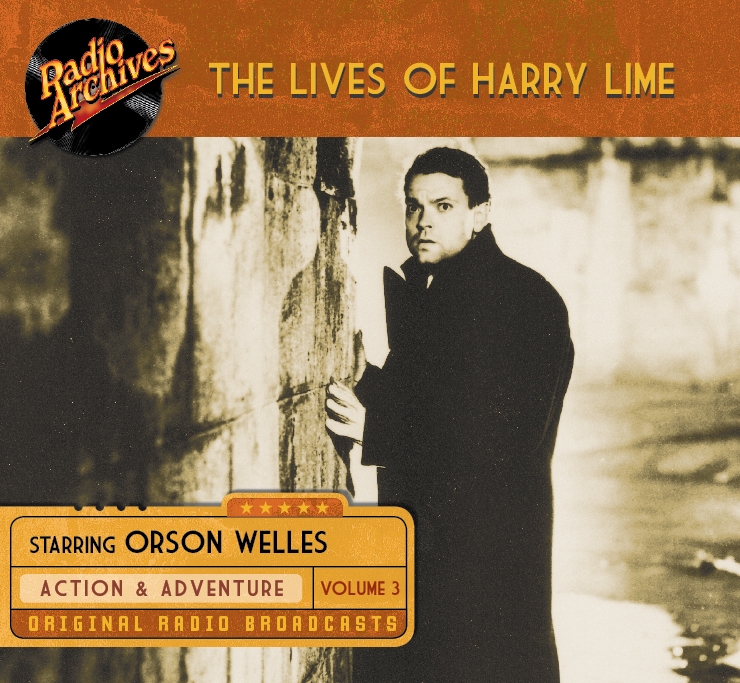

At the end of that movie, directed by Carol Reed, Welles’ genial but callous war profiteer is gunned down in the sewer tunnels beneath Vienna. Yet, because of the movie’s popularity, Harry Lime lived again via a BBC radio show that ran for 52 episodes between 1951 and 1952. Given that the character was onscreen in the movie for a mere five minutes, Harry Lime lived longer on radio than he did in film.

The Lives of Harry Lime focused on all the shady shenanigans Lime concocted prior to his appearance in The Third Man—dabbling in art forgery one week, a little light espionage the next. The producer paid Welles himself to voice the character.

Hiring the movie Harry Lime to give voice to the radio Harry Lime helped attract an audience to the show, but it also caused problems. If Welles wasn’t in charge, he could be difficult to work with. He frequently complained about the quality of the scripts for the show, and at one point said he could easily write better ones if he got paid for them. Fine, the producer said, you do that.

“A few weeks later, six scripts arrived and I paid him,” the producer later told Callow. “And the shows were, I wouldn’t say that much better, but Orson was happy and I was happy, until I had a ring at my doorbell one morning.”

The caller was another writer, who said Welles had hired him to write six scripts for the show but never paid him. He showed the producer carbon copies of the scripts that Welles had submitted as his own.

The producer was in a fix. He didn’t want to offend his star but he knew he had to say something. The next time he saw Welles, he told him about the other writer demanding money.

“Orson looked me straight in the eye,” the producer told Callow, “and said, ‘Don’t pay him. They were very bad scripts.’”

One radio script attributed to Welles (rightfully or not) was titled “Man of Mystery.” The show, which aired in 1952, concerned Harry Lime being hired by the amnesiac millionaire “Mr. Arkadian”—note the extra “I”—to trace his history prior to 1927. In this version, Welles himself plays the investigator, not the subject of the investigation.

Here’s how Welles described the radio-to-screen transition to Bogdanovich: “I wrote about seven of those scripts in a couple of days. One of the plots I thought up in a rush suddenly was that plot—and I realized that the gimmick was super. It came from just throwing together a lot of bad radio scripts.”

The radio version is lighter in tone than any of the movie versions, which offer bits of slapstick comedy but an abundance of menace and murder. In the radio show, Raina mocks perpetual con man Lime for falling for someone else’s con: “Oh Harry, you should’ve known better than to believe that one.”

Speaking of cons, some people—including biographer Leaming—believed that the movie was based on the novel by the same name, written by Welles. It was in fact an adaptation of the movie script that was written by Welles’ friend and sometime publicist Maurice Bessy. When Bogdanovich inquired about the book, Welles set him straight.

“When you wrote the novel of Mr. Arkadin…” the young director began.

“Peter,” Welles said, “I didn’t write one word of that novel. Nor have I ever read it.”

Bogdanovich pointed that some people “talk about the ‘beautiful’ style of your writing in that novel.”

At which point Welles joked, “Maybe I did write it, at that.”

* * *

At this stage in his career, Welles’ grand plans constantly stumbled over the question of how to pay for it. As a result, he often shot his pictures piecemeal, later putting everything together in the editing room.

Patricia Medina, playing Mily, shot all her scenes in 10 days, including a remarkable one that takes place aboard Arkadian’s mega-yacht, rocking violently in heavy winds. When she first looked at the set for that scene, she was startled to find it completely bare.

The next morning, when they were ready to shoot it, the set had been furnished with expensive furniture—all of which, she learned, Welles had liberated from the lobby of the Madrid Hilton. According to Welles scholar Jonathan Rosenbaum, “He announced that they had time for only two takes because the furniture had to be returned before it was missed.”

Welles contributed more than just purloined furniture to the film’s look. He told Bogdanovich that he “had to paint by hand everything in Michael Redgrave’s antique shop…Night after night—all night long, by myself, when the day’s shooting was over. God, the work that went into that.”

* * *

The man keeping this shoestring production afloat was a magazine editor with zero prior experience with moviemaking. A Frenchman named Louis Dolivet, he supposedly found financing in Switzerland for the Spanish production of what was at first titled “Masquerade.”

Welles and Dolivet became friends when they were both married to actresses—Welles to Rita Hayworth and Dolivet to Beatrice Straight (who would later win an Oscar for Network). The cosmopolitan Dolivet became Welles’ mentor on global issues, encouraging him to write essays and give speeches and consider a political career (Welles did the first two, but refused the third). According to the Washington Post, he “was an extremely handsome man, a gifted writer and an eloquent orator.”

He was also not what he appeared to be—in other words, a man of mystery.

His real name was Ludovici Udeanu. He originally hailed from Austria-Hungary, not France. And at the height of the McCarthy era, several congressmen denounced him on the House floor as “a very dangerous Stalinist agent.”

He denied the charges, but the accusation he was a spy dogged him to his dying day. It didn’t help that his brother-in-law, New Republic editor Michael Straight, was long rumored to be the “fifth man” in the Cambridge University club that included the spies Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Kim Philby and Anthony Blunt. A 2008 book, The Last of the Cold War Spies by journalist Roland Perry, identifies both Dolivet and Straight as bona fide KGB agents.

Why would a KGB agent line up financing for an Orson Welles film? I don’t know, but there is one version of the Dolivet story that suggests the phony Frenchman stole money from his Soviet masters. Perhaps this was a way to launder it—which would be a nice irony.

“His intriguing web of shadowy social and political connections is straight out of a Welles film,” the artist and critic Brian O’Doherty pointed out in a piece on Mr. Arkadin in ArtForum.

* * *

Welles shot Mr. Arkadin in five months in 1954, mainly in Spain, with some scenes filmed in France and Germany. He worked with a virtual United Nations of a crew: “I had a French cameraman, an Italian editor, an English sound engineer, an Irish script girl, a Spanish assistant,” Welles told one interviewer.

Welles spent eight months editing the footage, redubbing some of the other actors’ lines himself, getting so drawn into manipulating the images and plot that by one report he was progressing at the rate of two minutes a week.

Welles gave his friend Dolivet a brief cameo in the film, where he’s seen giving Van Stratten information about a witness. Once the shooting was done, their friendship grew strained as Dolivet became increasingly frustrated at Welles’ post-production pace. Welles blamed Dolivet’s inexperience.

“Louis had never been near an editing table!” he told Barbara Leaming. “And I’d made quite a lot of pictures by then, and I knew exactly how long it takes to edit a picture.”

Ironically, for a movie about a smuggler, Welles’ other nemesis proved to be French customs. Inspectors insisted on searching for and stamping the ends of each reel of film shot in Spain and subsequently shipped to the director, which added hours to each editing session.

Dolivet kept setting deadlines that Welles kept missing. Welles even withdrew the Spanish-language version—filmed at the same time as the English version, but with two scenes re-shot with Spanish actresses—from competition at Cannes because he didn’t think it was ready.

For explanation of this director-producer dynamic, Parker Tyler, in a 1963 essay in Film Culture, points to Welles’ own story of the scorpion and the frog: “The scorpion must cross a stream (that is, Welles must make a film), but, to do so, he must enlist the help of a frog”—i.e., a producer—whom he stings, “at his own expense.”

Dolivet the Frog gave Welles the Scorpion one last chance to make it across the river, setting a Christmas deadline. Welles missed it. Ho ho ho.

At that point, Dolivet took charge of editing Welles’ copious footage, which launched the making of multiple versions of the movie. Meanwhile the producer sued Welles, and the case dragged on for three years before Dolivet at last let it drop.

“They took it away from me!” Welles told Leaming. “And they completely destroyed the movie, more than any other picture of mine has been hurt by anybody.” Fans of The Magnificent Ambersons may find that hard to believe, but it’s true.

Welles moved on from the Arkadin disaster, making Touch of Evil, The Trial, Chimes at Midnight and F for Fake before he died in 1985 at the age of 70.

But the pain of seeing Mr. Arkadin butchered remained with Welles for decades. In a 1982 magazine interview, he said of his loss of control over Mr. Arkadin: “It’s as if they’d kidnapped my child!”

* * *

Dolivet the secret agent effectively sabotaged Welles’ design for the film, eliminating much of the flashback structure that gave the movie its resemblance to Kane.

Meanwhile Warner Brothers, which had agreed to distribute the film, requested a new title, which Welles supplied, turning Mr. Arkadin into Confidential Report—the first version to make it to a screen..

The world premiere took place in London, in August 1955. Neither Welles nor his wife and co-star the countess showed up, so they could avoid seeing the hated Dolivet.. The British press found the movie too puzzling to take seriously. Punch declared it “an exciting film to see, provided you don’t let yourself get mad at it.”

The Spanish-language version opened in Madrid around the same time. Then came the Paris premiere in June 1956. The influential French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema swooned. Two years later its editors declared it to be Welles’s greatest film and included it on their list of the 12 greatest films ever made.

Nevertheless, the public stayed away in droves.

“Whatever may have been done to the movie in the cutting room,” notes Charles Higham in Orson Welles: The Rise and Fall of an American Genius, “it was simply too grotesque, too bizarre, too specialized, and too unpopular in its theme to attract the mass public Welles needed.”

Perhaps because of its poor foreign box office and Welles’ own faded reputation in the U.S., his new film didn’t make it to an American theater until seven years after its European premieres.

* * *

This is the point where the detectives take over the story.

At some point in the late 1950s, Bogdanovich—then a writer, not a director, not yet—became enamored of Welles’ work. In 1961 he helped organize a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art. He also penned a pamphlet for the show, “The Cinema of Orson Welles,” in which he lamented the poor editing of Confidential Report but also called it “perhaps his most ambitious film to date.”

Around this time, Bogdanovich discovered, in the vaults of Hollywood film distributor, another version of the film, one that still had its flashback structure mostly intact. This is the “Corinth” version, which film scholar Jonathan Rosenbaum has declared to be “the version of the film closest to Welles’ conception.”

How did it get there? Why was it sitting in the vault waiting for someone to discover it? I contacted a number of Welles experts asking how a different version of a movie shot in Spain and released in Europe wound up in Hollywood. No one knew the answer. I guess we should just be happy it turned up.

Bogdanovich persuaded New Yorker Films to premiere this version at a New York City theater in 1962. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther declared it to be “in turn, baffling, exciting, infuriating, original and obscure. It is also, from start to finish, the work of a man with an unmistakable genius for the film medium. In other words, it is typically Orson Welles.” As for Welles villainous turn, he called him “flamboyant as ever…His Arkadin is less a performance than a presence.”

Ever since Bogdanovich’s successful spelunking expedition uncovered the Corinth version, film sleuths have spent decades searching for other pieces of the lost Welles masterpiece. Their digging has unearthed Welles’ editing notes, Dolivet’s correspondence and other tantalizing clues to what might have been. Rosenbaum in particular has been diligent in his search, at one point even penning a 1992 piece for Film Comment magazine titled “The Seven Arkadins.”

This cinephile scavenger hunt reached its apotheosis in 2016 when Criterion produced what it called The Complete Mr. Arkadin. The title is a lie, because of course Mr. Arkadin can never be complete. In each version there are pieces missing.

But the Criterion release comes close, offering three episodes of the radio show The Lives of Harry Lime, the book Welles didn’t write, interviews with Callow and Alden, commentary by Rosenbaum, and three versions of the film: Confidential Report, the Corinth version, and a new, slightly longer cut, created just for this release, which they call the “Comprehensive” version.

I borrowed a copy of the Criterion release and watched the other two versions of the movie. Confidential Report seemed somewhat boring without the flashbacks, like watching a Kane that starts with his childhood and ends with him dropping the snow globe.

Meanwhile the “Comprehensive” version reminded me of the empty airplane—it moves along at a good clip, but the person who’s supposed to be piloting it is nowhere to be seen. Perhaps most telling is the fact that this is the only version that shows the plane at last crashing into the ground, much like Welles’ own hopes for a big box office success. Ah well, at least we all got a good story out of it.