When I agreed to write a magazine article on past-life regression therapy, I had no idea that my research would inspire my first thriller. The assignment did not get off to a promising start.

Picture this: A damp, chilly church basement on New York’s Upper West Side where forty people hankering to get in touch with their previous incarnations lay on rubber mats spread across the floor and, with eyes closed, were sinking into a hypnotic trance. “Feel your muscles melt into the floor. Focus on your breathing. In. Out. In. Out,” the workshop leader intoned, his voice so melodic he was practically singing. “Now visualize yourself in a hallway with closed doors on either side. I’m going to count backwards from ten, and when I say one, open the door closest to you and say hello to your former self.”

From every corner of the room I heard a chorus of deep breathing, then sighing, then “ohs” and “ahs,” and when I opened my eyes to peek, it appeared that all the other past-life voyagers had landed in a former lifetime, while I remained stuck in the present, feeling like a total flop at the whole enterprise.

Still, I’d signed a contract and needed some kind of experience for my story, so I booked a private session with the psychologist who’d led the workshop. As soon as he opened his front door, I warned him that I was preternaturally resistant to hypnosis and would be a tough nut to crack. “We’ll see,” he said, his blue eyes twinkling as he led me into his office and motioned for me to lie down on the couch.

I have no memory of what he said next, but suddenly I was gasping for air as I witnessed myself being murdered. The experience left me reeling. Although it felt cathartic, was it for real? I was a journalist. I needed proof that what I saw wasn’t simply the product of an overactive imagination that veers toward the dark side.

The proof came a week later when I described the experience to my shrink. Fully expecting him to encourage me to explore the symbolism of being killed, I was surprised when he pulled a book off his shelf and handed me Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation by Ian Stevenson, M.D. Dr Stevenson was a professor of psychiatry at the University of Virginia who for decades had been studying children with spontaneous recall of a previous life. I took the book home and devoured it.

Though Stevenson dismissed cases of hypnotic regression as too vague to be verifiable, he believed that the 2,500-plus children he’d studied who typically began speaking about a past life between the ages of two and four did present credible evidence for reincarnation. The specifics these kids recalled—documented by Stevenson and his team—blew me away. Most of them correctly identified the names of people and places they had no earthly way of knowing, and many insisted that their present-day parents were not their “real” parents. What’s more, much of what the children seemed to know occurred late in the life of the person they remembered. Fully seventy-five percent described suffering a sudden, violent death, and a significant percentage exhibited phobias, such as a terror of drowning or guns, related to the manner of death. And many of the kids had been born with birthmarks that corresponded directly to wounds sustained by the deceased.

I’ll never know whether my own “memories” retrieved under hypnosis were authentic, but I was grateful for the magazine assignment. Without it, I probably never would have come across Dr. Stevenson’s research, which seized my imagination and wouldn’t let it go. How would I react, I wondered, if one day my toddler suddenly announced that she had another mom and or that our home wasn’t her real home? Would I believe her or chalk her claims up to a wildly creative mind? Would I question her to find out more about what she said she remembered, or be so undone by jealousy at the very thought of her having another mom that I’d stifle the conversation? And what if she said she’d been murdered? How would I deal with that?

Ever since having a child in my early 20’s, I’d written about motherhood in many different forms—plays, poetry, essays, memoir. I’d never written a novel, but I knew immediately that the story of a child who believes he’d been murdered in a previous life was ripe for a thriller. So many intriguing questions to consider: How would the child’s parents react to statements that their little darling had lived before? How would the family of the deceased handle the news that some pipsqueak was running around claiming to be their dearly departed? Most thrilling of all for a thriller, what if the murderer who’d never been caught was lurking in the shadows nearby?

Motherhood and murder came together in my mind as two essential threads of my story, but I soon realized that there was no way to write about the possibility of reincarnation without taking a deep dive into the metaphysics of it. Was rebirth real or just the wishful thinking of humans terrified of death? In another stroke of serendipity, around the time I was researching the article I’d also been dipping into meditation and attending talks by Tibetan Buddhist lamas, including the Dalai Lama, who were acknowledged reincarnations of the late masters for whom they were named. These teachers spoke as casually about past and future lives as they might about last Thanksgiving or next Fourth of July. And suddenly, exploring the question of whether consciousness survives the death of the body became the third—and by far, the juiciest—thread of my thriller-to-be.

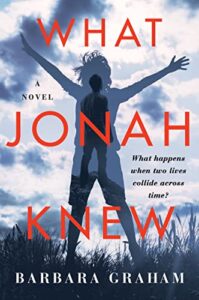

Then one spring day while walking down the street in New York City, the story of What Jonah Knew came to me as a sort of download, whole and unbidden. I knew in that moment exactly where the novel should begin and where it needed to end. I even sensed some key turning points along the way. But most of all I understood that I simply had to write it. That contract was non-negotiable. Ironically, however, the magazine article that got the whole thing started was killed before the issue went to press.

***