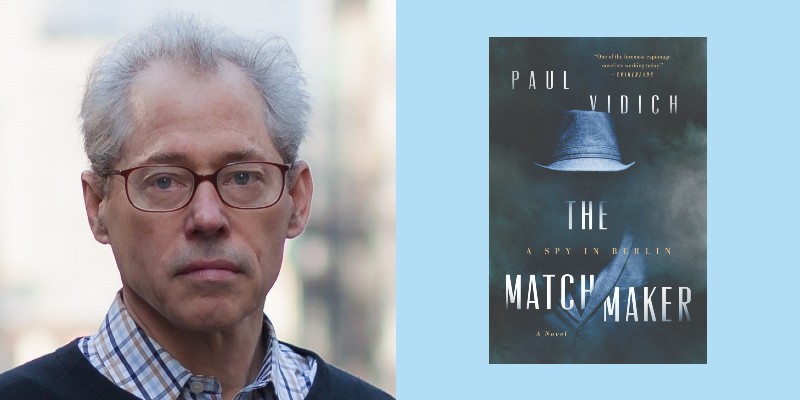

The novels of Paul Vidich are far removed from the sheen and opulence of James Bond, and feel more at home with the wry wit and stuff air of John le Carré’s George Smiley. In Vidich’s world, few can be trusted and the double-crosses often become triples, creating a gray, murky world of uncertainty and intrigue that propels his lush prose. Vidich’s latest, The Matchmaker (available February 1, from Pegasus), could very well be his best yet—and it features some unexpected influences. I had the chance to discuss the new novel, Vidich’s views on the spy genre, and what role—if any—comic books play in his literary DNA.

ALEX SEGURA: Paul, your latest, THE MATCHMAKER, feels like an intentional gear shift for you—in terms of structure and protagonist. Can you tell us a bit about it and the inspiration behind it?

PAUL VIDICH: Anne Simpson, a young American woman who works as a translator in West Berlin, is notified that her East German husband has disappeared. She begins her own investigation and discovers that he lived a double life as a Stasi spy. Her marriage was arranged by an East German spymaster—the Matchmaker—who identifies vulnerable women living in West Berlin and arranges for them to meet his agents and become unwitting accomplices in their husband’s espionage.

Nikita Khrushchev once called Berlin “a swampland of spies,” and that alone was enough of an endorsement for setting the novel in this storied city. During my research, I came across the autobiography of Markus Wolf, the legendary chief of East German counterintelligence, and I was fascinated to read how he used the human need for affection to create a network of “Romeos,” men who married innocent women as a cover for their spying. Essentially, Wolf turned love into tradecraft. I have always been interested in the trope of the falsely accused person who must find the criminal to prove her innocence. I was fascinated by the idea of a vulnerable American woman living overseas in love with a husband, only to discover everything she had come to know about him was false, everything was a lie. How do you recover from that?

I’d guess you don’t. That’s an intense premise. Your novels always feel very lived-in, for lack of a better term. How research-heavy is your writing process? Can you talk about what went into THE MATCHMAKER and how does it compare to some of your other novels?

I do six months of extensive research before I sit down and write a novel. Research allows me to inhabit a unique place in a particular time, acquiring the details needed to build a convincing world. I placed this novel in 1989 as the Berlin Wall falls. While the historical context is accurate, and the setting hopefully convincing, the characters and their world sprang from my imagination. I need to know a city well before I can set a story there and that requires a great deal of research.

For The Matchmaker, I read autobiographies of Stasi agents and I read accounts of the victims of Stasi surveillance. I was able to understand the hopes and fears of the men and women who were caught up in East Germany’s authoritarian system, and once I inhabited their world, I created Stephan Kohler, the Romeo who married to Anne Simpson while he carried on a double life with a family in East Berlin.

Dialogue is key for me: it’s a bit like wine. Great wine has a terroir, the uniqueness of the land, and characters also carry with them the uniqueness of their place of birth. I love that you can reveal a person’s whole personality with just a few lines of dialogue.

It truly is the hidden framework for the best novels—that’s what you remember. The zingers, or the witty exchanges. Now, when I was thinking about this interview I asked your publicist about comics—and whether you were a fan— mainly because your writing style is engaging but not overwhelming, if that makes sense. What I mean is your words filter through the mind in a way that allows the reader to form the images on their own, as opposed to, say, a barrage of detail. Could you talk a bit about comics and graphic novels, and how you engaged with the medium?

I suspect graphic novels played a part in how I visualize stories, but a greater influence on my style came from an early love of movies. A movie’s production design sweeps the viewer into the story almost effortlessly, and the hard work of storytelling falls to the script writer and the actors. Good production design delivers to the viewer the images needed to believe the story.

Writing has a different challenge. The images created in the reader’s imagination must be provoked by words on the page. Too many words destroy the wanted effect and too few, or words that are too unadorned, don’t allow the reader to complete the picture. I strive to invite the reader into the story with descriptions that create a memorable sense of place. My writing tends to be scene driven, so the curtain opens and the reader is in the casino, or at the border, of on top of the Berlin Wall. Sometimes, the world is seen through the eyes of the protagonist and at other times with the distance of the narrator.

Yes, exactly. The onus is on us to create the visuals—or at least enough of them to allow the reader to finish the job. Speaking of comics, who are some of your favorite comic book characters and creators?

The trio of men—Superman, Batman, Spider-Man—were the characters that I was drawn to as a young teenager. After college I joined Warner Communications, owner of Warner Bros., which was the parent of DC Comics and publisher of the early super hero comics. DC Comics was across the street from my Rockefeller Center office and the proximity of my work to the place of super-hero creation gave me a special allegiance. The comics had moral clarity about good and evil, which made them satisfying, and set them apart from the ambiguous ethics of the Cold War.

I was drawn to your work after spending a good stretch of time reading the Smiley novels, and while I bristle at calling anyone an “heir apparent,” because I think it waters down your own efforts, you do share many of the strengths that draw me to le Carré’s work. Which leads to my next question: what makes a good spy novel, in your estimation? What are some of your favorites?

The spy genre is a tall tent poll that encompasses straight-forward thrillers and literary novels. The only thing the spy subgenres have in common is that one or more characters is a current or former spy. But then the similarities fade. I prefer the literary work—language matters to me. The literary spy novel tends to deal with identity, duplicity, and betrayal. Plot is important, but the novels are character driven. They adhere to the basic principle of storytelling: setting establishes character and from character emerges plot.

Spies are ideal subjects because they operate at the limits of civilized behavior and their work requires that they betray acquaintances, suborn friends, and operate as legally sanctioned criminals. Murder is an art form. I am fascinated by this world. We all lie a little in our lives, but the spy’s life is all about deception and betrayal, and usually it is done for a higher purpose, although at the end of the Cold War spies often operated in the ruins of abstract ideologies and failed promises. Spy novels set in the later Cold War period often feature protagonists looking to save themselves from a decaying political system.

Literary spy novelists I admire include Graham Greene, John le Carré, Eric Ambler, Ian McEwan, Joseph Kanon, Len Deighton, Kate Atkinson, and Phillip Kerr. Any of their books is worth picking up. I don’t include Ian Fleming in this group. He writes well, but there is a superficial gloss to his characters. I prefer his book of essays, Ian Fleming’s Thrilling Cities, an account of cities he visited in a 1959 round-the-world trip paid for by London’s Sunday Times. His description of New York City is quite brilliant. He begins the chapter, “I enjoyed myself least of all in New York.” The essay ranks up there with other masterful essays of the city, including E. B. White’s “Here is New York,” and Joan Didion’s “Goodbye To All That.”

For me, I often find that protagonists…show up. Appear in your mind almost full formed, and those are the ones that really stick. Anne Simpson is a compelling and fleshed-out character. How did she first appear in your mind? What made her the ideal protagonist for this story?

I first saw her as ‘the innocent abroad.’ I developed a dossier on her that never appears in the novel, but to create a story for her, I had to know her intimately—where she was born, her early childhood, divorced parents, failed first marriage, gift for languages. All that happens off stage in the book’s pre-history. As the novel opens, she is at a vulnerable point in her life, frightened by the loneliness of her divorce and open to the affection of a handsome stranger. It is this vulnerability that allows her to become empathetic, trapped in a web spun by powerful and indifferent intelligence bureaucracies.

Her male counterpart might be Roger Thornhill (played by Carey Grant) in North By Northwest, a New York ad executive who is mistaken for a Soviet spy and is a target for murder. Unable to convince the police of his plight, Thornhill has to expose the spy network to reclaim his innocence. Anne Simpson, my protagonist, goes on a similar journey.

Can you share what you’re working on next?

My next novel is The Good Shepherd. It is set in Beirut in 2006 during the 34-day Israeli invasion of Lebanon. I’m leaving behind the Cold War and taking up the War on Terror.

___________________________________

The Matchmaker, by Paul Vidich, will be released by Pegasus Books on February 1, 2022.