Books adapted from movies don’t have a sterling reputation. They’re often viewed as slapdash cash-grabs by writers-for-hire, despite some notable examples to the contrary—for example, Arthur C. Clarke’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” (written concurrently with the screenplay) and Alan Dean Foster’s “Alien.”

Now Quentin Tarantino is providing his own twist on this odd genre with the novelization of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” the 2019 movie he wrote and directed. The story follows fading Western-movie star Rick Dalton (played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the movie) and his stuntman/assistant Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) as they navigate Hollywood in 1969, drinking and talking and lurking around movie sets. Various stars, including Sharon Tate and Bruce Lee, drift around the edges; Charles Manson and his band of murderous hippies lurk in the darkness, readying to do something terrible.

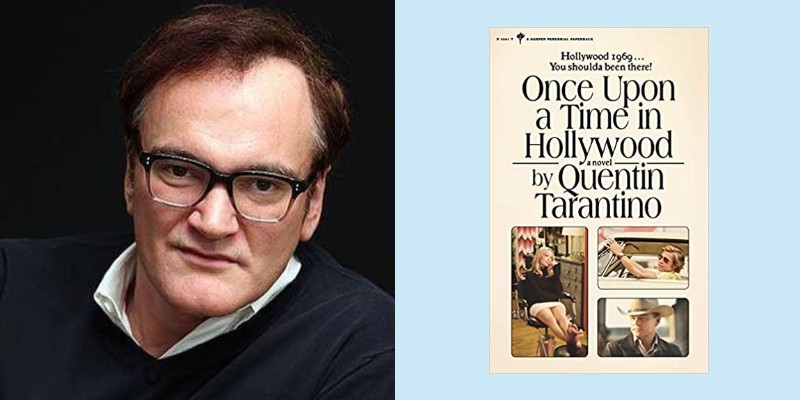

At almost 400 pages, the book is quite long, and formatted like one of the pocket paperbacks of yesteryear. It’s also written in a very colloquial style that’ll be instantly familiar to anyone who’s ever read one of Tarantino’s screenplays; but unlike a screenplay (usually limited to somewhere between 120 and 180 pages), the novelistic format allows him to take long digressions into everything from the drinking habits of Golden Age movie stars to the thoughts drifting through Manson’s head.

If you pick up the book with the expectation that it’ll reproduce the movie’s beats, however, be prepared: This is a very different animal. Tarantino made some core changes to the narrative that makes the novelization of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” slower, weirder, and far more melancholy than its celluloid counterpart. Some spoilers ahead…

The Book Settles the Question of Cliff’s Wife

In the movie version of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” Cliff Booth is something of an enigma. Other characters repeat the rumor that Cliff killed his wife, but nothing in the narrative confirms it. There’s a brief flashback to him on a boat, contemplating a spear gun while his wife yells at him, but the film cuts away before he can potentially pull the trigger.

The book removes any such ambiguities. Cliff not only kills his wife on that boat, but the “shark gun” he utilizes for the deed blows her literally in half. In an especially Grand Guignol touch, the horrific injury doesn’t kill her instantly, leaving “hours” for the couple to lovingly reconnect about their relationship before she finally expires. It’s so surreal that you halfway wonder if Cliff, in his shock, hallucinated everything after he pulled the trigger; it’s either that, or Tarantino ignoring everything about human anatomy so he can indulge in a penchant for baroque gore.

Nor is the slaughter limited to Cliff’s wife. While the movie skims over Cliff’s service in World War II, the book goes into detail about all the countries he visited and the people he killed while in the Army. That’s in addition to shooting a couple of mobsters in Cleveland and murdering someone to save his beloved dog. Yes, the Cliff in the book is even more of a murder machine than the one in the movie, which is impressive when you consider the killing he does onscreen in the latter.

The Book’s Ending is Totally Different

The climax of the movie plays like the punchline to a sick joke: “What if, instead of invading the house rented by Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate, the Manson family hit the house next door—which was occupied by one of the most dangerous men in Los Angeles?” The answer, of course, involves a pit bull, a flamethrower, and various pieces of household furniture turned into weapons.

If you buy the novel expecting that home invasion described in loving detail, you’re going to be sorely disappointed. In fact, the fight is reduced to three-quarters of a page, and it occurs roughly a third of the way through the book. All the connections to the Manson family are dismissed with a shrug:

“The LAPD theorized the hippie intruders were frying on acid and out to perform a Satanic ritual. What isn’t a matter of theory is, those fucking hippies sure picked the wrong house.”

For a writer-director whose name is synonymous with bloody violence, this seems like a peculiar (and unexpected) choice, but it makes sense when you consider Tarantino’s larger aims for his story (both the film and novel versions).

By minimizing the movie’s climactic home invasion, the book forces you to focus on the Hollywood milieu and the characters’ place in it. Rick Dalton and Cliff Booth replaced an older generation of stars and stuntmen, and now they’re fading away, with their ultra-hip successors—as embodied by Polanski and Tate—taking over the limelight. It’s the Hollywood circle of life, and Rick struggles to accept that fact on a spiritual level. Without the mess and noise of a bunch of Manson acolytes getting burned up, the book makes you pay more attention to the quiet endpoint of Rick’s inner journey.

It’s Even Less of a Crime Story

By all-but-eliminating the movie’s climax from the book, along with one other violent incident at Spahn Ranch (where the Manson clan is holed up, and which Cliff visits late in both the book and the movie), Tarantino achieves what seems like the impossible for anyone familiar with his oeuvre: There’s virtually no crime, aside from the descriptions of Cliff’s past.

If you head into the book expecting it to be Tarantino’s take on crime fiction, in other words, you’ll be solely disappointed. If you approach it as a fictionalized take on Hollywood in 1969, sprinkled liberally with anecdotes about real-life actors and directors, you’ll be quite pleased. Maybe someday Tarantino will actually sit down and write a crime thriller that emulates the work of his heroes, including Elmore Leonard—but “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” is not that book.

Tarantino’s Very Personal Cameo

Tarantino has not one but two cameos in the book, both near the end. The first is a brief flash-forward of sorts for a precocious child actor who performs alongside Rick: “Frazer’s only nomination for the best-lead-actress Oscar was in Quentin Tarantino’s 1999 remake of the Jon Sayles script for the gangster epic The Lady in Red.” In reality (or our reality, at least) Tarantino never made that movie.

Later on, near the novel’s end, Rick and Cliff (with some pals in tow) drift into a bar where a piano player named Curt is playing the classics. They fall into conversation, and “Rick signs a Drinker’s Hall of Fame cocktail napkin to Curt’s son, Quentin, addressing it to ‘Private Quentin,’ making sure to check the spelling.” Curt discusses the movies he watches with Quentin, including one of their favorites, “The Fourteen Fists of McCluskey,” which Rick starred in.

If you listened to Marc Maron’s recent interview with Tarantino, you know that Curt—Curtis Zastoupil—was Tarantino’s stepfather in real life. Curtis was a nightclub musician, which freed up time during the daylight hours to watch movies with his stepson. By inserting Curt, the novel takes on an intensely personal dimension that the film version lacks; you sense how much of a passion project this was for Tarantino.