Refugees are a global scandal. Let me explain. Over the past five hundred years or so, successive political regimes in Europe and the European settler colonies have conjured up the illusion that the world is divided into discrete territorial units governed by a central authority. One of the most pernicious results of this illusion is the notion that every human being must belong to one of these territorial units, be it by birth or blood.

Refugees blow that illusion to smithereens. That’s why they are a scandal. The world’s governments try their best to contain that scandal, sometimes in a benevolent fashion, often not. And still, they keep coming because the very governments complaining about refugees do their level best to create more.

According to the latest count of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there are 68.5 million forcibly displaced worldwide. Of those, some 40 million are internally displaced, that is, they aren’t even qualified for refugee status. Then there are the 25.4 million who are refugees and under the mandate of the UNHCR or UNRWA. Finally, there are 3.1 million who are seeking asylum in other countries.

In my pre-fiction career, I’ve worked as a professor of International and African studies. During those decades, I’ve always been occupied by the clash between the territorial state and the non-territorial forces. The centrifugal dynamics of human relations, of course, predate the modern state by millennia. Being human means being mobile. Human history is a history of movement. The centripetal force of the territorial state is a much more recent phenomenon, and quite artificial to boot. It requires constant reminders (national anthems, flags, tombs of unknown soldiers), but it also demands force because the territorial state instills inside vs. outside thinking. The inside is safe, predictable, maybe even democratic, whereas the outside is wild, foreign and dangerous.

In such a world, the refugee is a destabilizing factor, one to be controlled, excluded, marginalized, even criminalized. And here, finally is the link to crime fiction. Much, though not all, of crime fiction tells stories from the margins of society. Its characters, either overtly or psychologically, aren’t part of the regular society. They live, act and commit their crimes outside of the dull everyday lives of the majority. Or they investigate and solve crimes in equally marginal milieus. Given this state of affairs, you’d think there’d be a fair number of books including refugees. There are some, but not a lot. What follows below are books that may or may not be strictly crime novels. But then, the very act of crossing a border without proper authorization constitutes a crime in much of the world, so any novel including refugees is by definition also a crime novel. Here then, in no particular order, are some novels dealing with refugees.

A Most Wanted Man, John le Carré

Issa Karpov is the poster child for everything people fear about refugees. He’s a Muslim, albeit a strange one, according to the Turkish family, which, practicing Muslim charity, ends up giving him a bed. He’s illegal, showing up in Hamburg, Germany without papers after having paid traffickers to get him there from Chechnya. He may be a terrorist, at least that’s what the Russians claim. And to top it off, he’s looking for an obscure private bank, that’s known to have laundered shady Russian cash in the past? No wonder intelligence services from various parts of the world are interested in his sudden appearance. But there’s also Annabel Richter, a lawyer and human rights advocate, who wants to help Issa. The plot unfolds in sadly predictable ways as the competing intelligence services aim to use Issa for their respective goals, while Ms. Richter tries her level best to protect Issa. Her role here is one of the few examples in crime fiction of the uphill struggles that charitable organizations who fight for refugees face. It’s not much of a spoiler alert to say that in this novel, like in so many of John Le Carré’s later novels, the good guys don’t win. The apt line from the book is no surprise, “Justice has been rendered, man. American justice.”

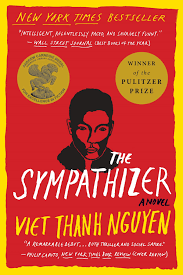

The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen

This story starts in a reeducation camp in North Vietnam where the unnamed protagonist is writing his confession. He’s a walking contraction. He’s a North Vietnamese mole, who worked for a general in 1975 South Vietnam. He’s the son of a French priest and a Vietnamese mother. He went to college in the US, but was brought up in Vietnam. After Saigon is taken over by North Vietnamese forces in 1975, the protagonist becomes a refugee. First in a miserable camp in Thailand, then in Los Angeles. He navigates the complicated terrain of being a refugee and a spy with the crazy notions of a twenty-something guy. Along the way, he acts as a consultant for an American film director making a movie about the Vietnam War. Those passages are probably the best of the book. The refugees are bitter about the betrayal of the United States and harbor foolish dreams of reconquering their home. The protagonist doesn’t quite fit that mold. As a cultural hybrid, he seems like a floating signifier on which any given context inscribes new meaning. One of the best lines in the book is: “And I was thankful, truly! But I was also one of those unfortunate cases who could not help but wonder whether my need for American charity was due to my having first been the recipient of American aid.”

Exit West, Mohsin Hamid

Not really a crime novel, Exit West explores what happens to the lives of those who flee. Nadia and Saeed meet each other in an unnamed city in an unnamed country, although the similarities with Syria or Afghanistan are unmistakable. As they fall in love, the city around them falls into chaos. Militants take over and make life there impossible. In a magical realist twist, the two hear of secret doors that allow for escape. They find one and end up in Mykonos, Greece, amidst a host of other refugees who lack the bare necessities for living and wait for onward passage anywhere. With the help of a compassionate Greek woman they find another door that leads to London where they experience the full force of anti-refugee sentiment similar to that we’ve seen associated with the aftermath of Brexit. One more door leads to Marin County in the US. By that time, each is no longer the person with whom the other fell in love. Home becomes merely a distant memory. They rebuild their lives in a new environment. There is a quiet sadness to this novel, as their falling out of love mirrors their losing the link to what used to be home. The pertinent quote here is, “All over the world, people were slipping away from where they had been, from once fertile plains cracking with dryness, from seaside villages gasping beneath tidal surges, from overcrowded cities and murderous battlefields, and slipping away from other people too, people they had in some cases loved, as Nadia was slipping away from Saeed, and Saeed from Nadia.”

Havana Libre, Robert Arellano

Pediatrician Mano Rodriguez, first introduced in Havana Lunar, lives in the attic of the house his family owned before the revolution. He runs a neighborhood clinic on the ground floor and also works at the pediatric hospital. It’s 1997, el Período Especial en Tiempo de Paz has been in effect for seven years, he still only earns two-hundred pesos, and even the prostitutes on the Malecón tell him to buy some pants that fit. It’s also a time when bombs go off in the tourist hotels, set by exiles who want to cripple Cuba’s emerging tourist economy. He comes across one such attack and is unable to save a victim. His old nemesis Colonel Pérez recruits him to infiltrate the refugee community in the most dangerous city in Latin America, Miami. Like The Sympathizer, these refugees have been in Miami almost three decades. They’ve created new lives, yet they still dream of overthrowing Castro, of going back home. They pursue their jobs during the week and spend their free time planning terrorist attacks. And they include someone Mano hasn’t seen in decades. This quote captures Mano’s first impression of Miami. “I see a real Maserati. It peels around corner with a shriek. There goes one hundred Cuban doctors’ lifetime fortunes on four wheels. I see men walking in under a great, lighted marquee for a strip club that announces, NUDE! NUDE! NUDE! and I cannot believe the pictures they show on the street.”

The Constant Gardener, John le Carré

At first glance, The Constant Gardener doesn’t seem to involve refugees. It’s a tragic love story wrapped in a spy story. The outward story is about Justin Quayle, mid-level diplomate at the British High Commission in Nairobi, sorting out who killed his wife Tessa. But only a little digging below the surface reveals refugees in various places. Wanza, the displaced woman who appears posthumously throughout the novel, is driven by poverty to Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum. Like many others there, she’s vulnerable to all kinds of predations, instigated by a global corporation and facilitated by local powers. Wanza is a placeholder for millions like her, whose livelihood in the countryside has been eliminated, condemning her to eke out a living in the slum. In the last chapters of the book, when Justin is about to put the final puzzle pieces into place, the story takes us to Camp Seven in South Sudan. There, Justin learns of the intricacies of food aid in the context of a civil war and meets some of the victims of that war. Even though the refugees in Camp Seven are considered a means of atonement for one of the crooks, they do highlight how elusive the concept of home is for millions of people in this world. The quote that stands out in this novel is, “With corporations it is always nobody. The big boss calls in the sub-boss, the sub-boss calls in his lieutenant, the lieutenant speaks to the chef of corporate security who speaks to the sub-chef who speaks to his friends who speak to their friends. And so it is done. Not by the boss or the sub-boss or the lieutenant or the sub-chef. Not by the corporation. Not by anybody at all, actually. But still it is done. There are no papers, no checks, no contracts. Nobody knows anything. Nobody was there. But it is done.”

The Foreign Correspondent, Alan Furst

Refugees aren’t just a recent global phenomenon. Historically, every war has generated streams of refugees. It’s not an accident that the original Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was adopted in 1951, to address the complicated refugee situation left by World War II. Alan Furst has made a career of writing spy novels that all take place at the threshold of World War II. But the seeds for all his novels were sown with World War I and the failure to settle the question of global hegemony in 1919. The twenty years of crisis that followed produced its own refugee crisis, and Furst captures the essence of it in 1938 Paris. This novel revolves around Italian refugees who fled the Mussolini regime to Paris and are publishing an underground newspaper that’s smuggled into Italy to give Italians the real news. Carlo Weisz, the new editor, after the Italian secret police agents assassinate the previous one, finds himself the target of pretty much every intelligence agency that’s active in Paris. The refugees in this novel have a professional background, lawyers, journalists, businessmen. They find themselves reduced to working menial jobs to make ends meet. Only Weisz is lucky enough to work in his chosen profession. The secret police agents after them, but the French authorities aren’t yet interested in protecting the refugees because Italy hasn’t officially thrown in its lot with Germany. In a way, this novel represents the flip side of Havana Libre. There’s the same desire to put undermine a regime from the relative safety of exile, although the existence of the Italian refugees in pre-war France seems more precarious than that of the Cuban emigres in Miami. But the story of having one’s life disrupted, of having to take jobs well below one’s qualifications are similar. A quote that stuck with me was “…spies and journalists were fated to go through life together, and it was sometimes hard to tell one from the other. Their jobs weren’t all that different: they talked to politicians, developed sources in government bureaux, and dug around for secrets.”

The Collaborator of Bethlehem, Matt Rees

The single largest refugee population lives in Palestine. According to the UNHCR, 5.4 million Palestinian refugees are registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Administration for Palestine Refugees (UNWRA). The origin of this population has been hotly debated for decades. For years, the official Israeli position was that the Palestinians fled because they were told by Arab governments that they could go back as soon as the Israeli forces were defeated. Historical research after the opening of British and Israeli archives now show that the use of violence, including strategic massacres, and the fear of that violence propelled the vast majority to flee their homes. Matt Reese situates his first Omar Yussef novel in the Dehaisha refugee camp near Bethlehem. Yussef teaches history at an UNWRA school and appalled by the absence of nuance brought about by the morbid effects of decades of occupation. Resistance fighters squeeze off rounds at Israeli positions during the night, the Israeli army responds by destroying roads, buildings and targeted killings. One such killing leads to the arrest of Yussef’s good friend and former student as a collaborator. The evidence gathered by Yussef points into a different direction, but the battle lines have hardened so much that the collaborator is given the death penalty without even a hint of a fair trial. Yussef has but two days to prove his friend’s innocence in a climate where revenge is the popular emotion. Rees draws out the ignominy of Israeli occupation but also highlights the power of Palestinian militias and their not so clean business undertakings. The novel shows what happens when the refugee status becomes permanent without a resolution in sight. It’s a sad combination of resignation and anger. After a bomb goes off in the wee hours in the morning at his school, Yussef, leading a policeman past the destroyed classroom, spells this out, “He’s seen this kind of destruction many times. It doesn’t even concern him that this is his own daughter’s classroom.”

Legitimate Business, Michael Niemann

When people fleeing violence or persecution don’t cross an international border, they aren’t refugees according to the international definition, they are called internally displaced people or IDPs. As the statistics at the beginning point out, they constitute the largest number of displaced people. The civil war in Darfur has displaced a massive number of Dafuris. The IDPs are caught between the Sudanese army and various rebel groups fighting each other over autonomy or even independence for Darfur. The IDP camp Zam Zam a few miles south of El Fasher, Sudan, is large, with some 50,000 people living there. Attacks on camps like Zam Zam are common. Like any city of that size, Zam Zam needs administration, services and police. Much of that is provided by UN contractors and aid organizations. The UN has learned the hard way that it needs police officers rather than military troops to keep the peace in such situations. So the all-female Bangladeshi police contingent—women make for better cops in camps, another insight learned the hard way—is the foundation of order in the camp. When one of these officers is shot dead, the official explanation is mob violence, but her best friend knows something else is afoot. Valentin Vermeulen, an investigator with the UN, listens to her and before long finds that there is something foul going on, and it’s bigger than anyone expected. The quote from this novel comes from the Nigerian commander of the UN forces in Darfur and highlights the weakness of UN peacekeeping. “I’m commanding a cobbled-together mission with a cowardly mandate only the UN Security Council could conceive. I’m responsible for the lives of twenty-five thousand soldiers and police whose countries and families expect them to come back alive…Do I wish I had a more robust mandate? Of course I do. That and a couple battalions of well-trained troops and I’d make sure nobody so much as farted in Darfur without my permission.”