There’s something alluring about safecrackers. The image of a black-clothed figure sneaking stealthily into a dark bank or mansion, turning the dial until the safe opens to reveal its treasures, is exciting and glamorous, despite its inherent illegality. There is a mystique, a level of advanced skill and polished competence to this particular crime that isn’t part of the common criminal’s repertoire. Perhaps that is what has long intrigued us about safecrackers. They abound in fiction, dating back at least to the early twentieth century, but there are also historical counterparts whose exploits are every bit as entertaining as those in the books and movies. Here’s a brief look at a few key safecrackers, both in fiction and in real life.

In keeping with their flashy reputation, several of the early fictional safecrackers were gentlemen thieves. E. W. Hornung’s Arthur J. Raffles is a man who moves about easily in society but is also a master of clandestine skills, including safecracking and the art of disguise. Known as the Amateur Cracksman (“cracksman” being an old slang term for a safecracker), Raffles, in between society events and cricket matches, still finds time to commit the odd safebreak or jewel theft. Charming, urbane, and kind at heart, Raffles is an early example of a criminal we are meant to root for.

Similarly, 1907’s Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar by French author Maurice Leblanc follows the unlawful undertakings of another cultured safecracker. Lupin (whose feats inspire the main character in the new, eponymous Netflix show) is an elegant man of the world who steals more for amusement than out of necessity. He’s a criminal, but he’s a dapper one, so all’s forgiven!

On the historical side of things was Adam Worth, who just might have been the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes’s archnemesis, Professor Moriarty. Worth, who was born in Germany and spent most of his early life in the eastern United States, moved back to Europe after things got too hot for him in America following several illegal enterprises. Worth eventually infiltrated Victorian London’s high society while creating his own crime syndicate. Over the course of his criminal career, he was involved in not only safecracking, but also bank robberies, art and jewel thefts, forgeries, and a host of other crimes. The larger-than-life Worth lived a life most criminals—even the fictional ones—could only aspire to. For a more detailed list of his daring deeds, I recommend The Napoleon of Crime by Ben Macintyre.

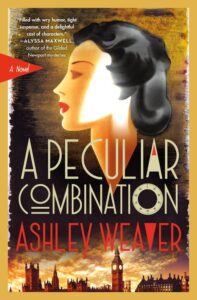

Perhaps even more compelling than elegant gentleman thieves, however, are safecrackers who use their illicit skills for good. My new book, A Peculiar Combination, features safecracker Electra “Ellie” McDonnell retrieving weapons plans from a safe before they can be turned over to Nazi spies. Ellie is safecracking for a cause, and there are others who have done so before her.

In O. Henry’s 1903 short story “A Retrieved Reformation,” milk-drinking ex-con Jimmy Valentine decides to open a safe that a child is accidentally locked inside, even though a detective is hot on his trail after several bank jobs. Because Valentine, who has used his abilities exclusively for robberies, is the only one who can save the child, it makes the moment all the more rewarding when he chooses to do the right thing.

Author Jack Boyle had something of a life of crime himself before embarking on a writing career. He reportedly started his first “Boston Blackie” story while serving a term in San Quentin. Boston Blackie, an honorable thief and safecracker, went on to have several adventures, practicing his safecracking art while making sure the really bad criminals went to prison. Never completely reformed yet using his skills mostly for good, Boston Blackie even made the jump from thief to private detective on radio and television.

Just as the gentleman thief is not purely an authors’ invention, the idea of using illicit skills for good is not confined to fiction. Perhaps the most impressive example is real-life safe-blower Johnny Ramensky. Ramensky had already developed something of a reputation for himself as a master criminal before World War II broke out, but, when his country was in danger, he set aside a life of crime. Ramensky, who used explosives in his safebreaking activities, decided to put these unique skills to use serving with the British Commandos. He worked with and trained others in the handling of explosives on several missions during the war, proving that sometimes it does, indeed, take a thief. Gentle Johnny Ramensky by Robert Jeffrey details Ramensky’s life and exploits, as both a thief and in service to his country.

Safecrackers, it would seem, are always good for a story. Whether they are gentlemen thieves stealing to maintain an elegant lifestyle or reformed criminals using their talents on the side of justice, the skill, stealth, and daring required for the task can’t help but win them admirers. Always calm and imminently capable, when a safecracker sets to work, we know the job will get done. And a part of us will always cheer knowing the story is in safe hands.

***