There’s an intriguing contradiction at the heart of Nicholas Meyer’s best work, a sort of chiaroscuro where the novelist, screenwriter and film director addresses dark topics in a disarmingly light manner. Even when he has addressed addiction (The Seven Percent Solution), climate change (Star Trek IV) or nuclear holocaust (The Day After), you never forget you’re in the presence of a great entertainer who delights in the stories he tells and the histories he unearths.

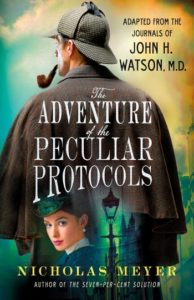

Meyer’s new novel, The Adventure of the Peculiar Protocols (Minotaur) his first in 26 years, finds the author in characteristically ebullient form as he sets Sherlock Holmes on the trail of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the origins of modern anti-Semitism. Writing during the Trump era in which purportedly outdated prejudices have once again risen to the fore, Meyer, 73, seems to feel a greater sense of moral responsibility than has been evident in his previous Holmes pastiches. And yet, there is an inescapable joy to the writing—jokey asides; clever footnotes; a scene which pays homage to the Hitchcock film The Lady Vanishes. His purpose may be grave, yet he seems to be having a great time pursuing it.

I grew up a Meyer fan (there was a Time After Time poster in my bedroom when I was an adolescent), but I first met the author in Bloomington, Indiana, where he was introducing a screening of the 1976 film adaptation of his novel The Seven Percent Solution (he wrote the screenplay and was nominated for an Oscar). Afterwards, walking through the college town with Meyer, I was struck by his sense of wonder and delight in everything around him. After we’d been walking a while, he suggested that we pop into a bookstore. While we were in there browsing, he picked out a classic mystery novel and suggested I read it. Seven odd years later, when Meyer spoke to me from his office in Santa Monica about Protocols, anti-Semitism, the Trump administration and the anxiety of being influenced, I reminded him of that moment. (This conversation has been edited for clarity and flow.)

Adam Langer: As you may recall, you and I met in Bloomington and we took a walk around the square and we went to a bookstore. Do you remember the book you told me I should read?

Nicholas Meyer: I don’t.

AL: As it turned out, I didn’t read it. I wound up giving it away and then I bought another copy about a couple of months ago. The book was The Daughter of Time, by Josephine Tey.

NM: Oh my God, you gave that book away? What a schmuck.

AL: Guilty. But what struck me was that there are a lot of through lines between that book and your work. When I think of the detective in that novel and how he tries to solve the historical mystery of the murders of Richard III’s nephews, it reminds me of how you’re bringing back Sherlock Holmes to solve a different kind of historical crime—namely, the origins of anti-Semitism.

NM: Well, the whole question of influences is a very tricky one. We may say we’ve been influenced by something, we may even think we’ve been influenced by something, we might like others to think we’ve been influenced by something. Bits and pieces of this might even be true. But sometimes we are influenced by things we that we don’t even know have influenced us. We’ve picked up memories and impressions that burrow so deeply into our psyches that we can no longer even trace their origins, yet they have profound effects on our thoughts and actions. It may be very chic to say I was influenced by Eisenstein or Proust, and maybe there are elements of truth in that, but I may have been equally influenced by Saturday morning serials. However, it is certainly true that The Daughter of Time made a tremendous impression on me. I was completely knocked out by it. It introduced me to a whole world of history and speculation. Whether and how and when that book leaked into all the elements that ultimately found expression in the Adventure of the Peculiar Protocols, I can’t say for sure. But to the degree that The Daughter of Time is one of those books that changed my life, it has to be said that there’s a trail.

AL: By that logic, though, we could say that the book could have influenced just about anything you’ve done to a greater or lesser degree.

NM: Yes, but I’m not the best judge of what I’ve done. To the degree that I’m entitled to have an opinion, I’d say that I see my book as actually a sort of stealth novel. While ostensibly about Sherlock Holmes, it’s really about something else entirely, possibly Donald Trump.

AL: But the idea of the story—sending Sherlock Holmes on the trail of the Protocols—that’s one you’ve been kicking around long before the Trump era began.

NM: This is certainly true. I was thinking about it even while you and I were walking around that square in Bloomington.

AL: What was the spark for finally writing it?

NM: The catalyst was Pogrom, a book by Steven Zipperstein about Kishinev and the pogrom there. I read it, and suddenly the last piece fell into place.

AL: Had you read The Protocols of the Elders of Zion before starting work on this book?

NM: No. I knew its reputation and I started to read it. The thing goes on forever. I would drop in on this or that page and I would say, “ok, I get it.” It is an endless repetition of the same thesis with a few odd, seemingly anomalous digressions onto things like interest rates. It’s just bizarre. Then I read Will Eisner’s graphic novel, which is a fancy word for comic book, about The Protocols. I never read all 300 pages of The Protocols. Life is too short, and I might add, so am I.

AL: What Holmes discovers about The Protocols—how it was translated from Russian to French, for example—is that all historically accurate?

NM: Yes. It’s not only a forgery; it’s a plagiarized forgery. Try to get your head around that one.

AL: And that’s part of what reminded me of Josephine Tey’s work—how excited her detective gets when he engages in historical detective work.

NM: You’re right. It’s what Holmes does too—you get hold of a thread and start tugging onto the thread, and then you’re bemused to discover that it leads to a string and you starts tugging on the string and it becomes a cord and the cord becomes a wire and the wire becomes a cable, and the next thing you know, you’re tugging at some enormous tapestry.

AL: So, this is your first Holmes book in 25 years.

NM: 26.

AL: How hard was it for you to get back into channeling Dr. Watson’s voice?

NM: On one level, it was very easy because I grew up infatuated with Victorian prose, whether it was Robert Louis Stevenson or Charles Dickens or H. Rider Haggard or Anthony Hope or George Eliot or Conan Doyle. I loved that writing and preferred it to the terseness of Hemingway, which was probably a reaction to all that. So, it was very easy. In another sense, since I wrote the book I’ve asked myself whether I wouldn’t have done better to reread some Watson. I’ve imitated Edwardian writing; I’m not sure I took enormous pains to copy Watson, and perhaps I can be faulted for that. I know other Sherlock imitators are very much at pains not to use words that Doyle never employed. They go to extraordinary lengths and I’ve never worried about that. By the same token, when I worked on Star Trek, I was really only glancingly familiar with the original television show. I just thought I would get the general idea of it, which allowed me to be freer and more spontaneous. I’m sure you could argue that there are writers who replicate Watson more precisely than I do, but I’m in the ballpark.

AL: You mentioned Star Trek, and I just have to ask you—when you were working on Wrath of Khan, which is generally thought to be the best of the Star Trek films, it wasn’t all that long after Leonard Nimoy had played Sherlock Holmes in a touring theatrical production I saw in Chicago. Did you and Nimoy ever talk about Sherlock Holmes on the set?

NM: I don’t remember discussing Sherlock with Leonard. What I do remember was noting the resemblance in a superficial sense between Spock and Sherlock. Later, when I was writing Star Trek VI with Denny Martin-Flinn, I threw in a line, which makes Holmes fans so happy, where Spock implicitly says that he’s descended from Sherlock Holmes.

AL: My memory of that Sherlock Holmes play is the reverse of yours. I remember Nimoy adding a line or ad-libbing a line about how love was not a logical thing, and the whole audience erupted into applause.

NM: Now that’s funny.

AL: Getting back to Protocols, though. When you described how others have approached channeling Watson’s voice, you used the term “at pains.” Yet one thing I admire about this book is that it is so far from being “at pains.” It seemed like you had an incredible amount of fun writing it.

NM: Oh, you’re right. You’re more right than you know. Even though I talk a lot, I don’t open my mouth unless I think I have something to say and, if I’ve kept my mouth shut on Sherlock Holmes for 26 years, it’s because I didn’t have an idea I could get really jazzed about. And there are two things that made me jazzed about writing this book: One is that I had an idea I really liked. The other was that, for a change, I was my own boss. In the business I’m in, I have to pay attention to a lot of other people and what they want and what they pay for. And a lot of times, I find that exceptionally frustrating. I’ve worked with some very bright and wonderful people, and I’ve also suffered idiots who make stupid requests or suggestions. Here, I was my own master. I was only limited by my abilities, whatever they might be, and I felt like I had been let out of prison.

AL: In addition to being very exuberant, the book’s also very timely with the global rise of anti-Semitism, which wasn’t necessarily the case when you started writing.

NM: Yeah, I was overtaken by events. And by the time I finished the book, even more so. For better or worse, I’m in the right place and the right time, which doesn’t make for a very cheerful topic.

AL: And yet it’s a very cheerful book about a not-very-cheerful topic.

NM: I know. That’s the thing I can’t quite get my head around. Because, as I was writing it, I knew I was tackling a serious subject. And it’s interesting that most people respond to it as something cheerful rather than something grim. The two things are sort of uneasily yoked in some kind of harness, and the cheerfulness seems to win out. Although, if you think about it longer, and you re-read it, you may find it more troubling.

AL: That same kind of duality is happening in your own mind, though; you’re having a splendid time writing about a grim topic.

NM: This is true. I can’t explain it. I’m extremely worried about the world I live in, and even more worried about the world that my children live in because they’ll live in it longer. That said, and maybe this is a flaw in the book, the exuberant part seems to outweigh the more troubling fundamental subject matter.

AL: If you had another shot at it, would you do something differently?

NM: That’s a very good question. Any answer I give would be superficial or problematic. Things come out the way they come out. It’s very hard to be someone other than yourself. Or at least it’s hard for me to be someone other than myself. I guess if you have a half-full glass sensibility then that’s what’s going to come out. Maybe a more gifted persona could assume a different personality more convincingly.

AL: It’s kind of hard to believe that when you’ve just spent two hundred some odd pages writing as Dr. Watson, who isn’t exactly you either.

I’m a sucker for magic tricks. I always believe. I always enjoy that moment when the houselights go down and the popcorn comes out.NM: You’re right, he isn’t. That’s certainly true, but he’s not entirely alien to me. He’s a good audience, and he’s a great audience for Holmes, and sometimes I wonder if I’m not a better audience than I am anything else. I’m a sucker for magic tricks. I always believe. I always enjoy that moment when the houselights go down and the popcorn comes out. It seems like a lot more fun than actually making the movie.

AL: What was your own experience with anti-Semitism?

NM: Virtually nil. When I was at (the University of) Iowa, I met a lot of people who had never met Jews before, but I didn’t experience anti-Semitism. When I moved to England, I had two experiences that I recall, and I had one experience in Los Angeles with a friend of mine who didn’t realize he was saying something anti-Semitic. But aside from those specific instances, never.

AL: A fairly charmed life.

NM: My life’s not over, and given the way things are drifting, I think I’m not wrong to be alarmed as I think many Jewish people are. In my life, with a couple of horrendous exceptions—the premature death of my mother at 45 and the still even more premature death of my wife at 36—I’ve been very lucky. There’s an anecdote I read somewhere. Someone recommended a general to Napoleon and said, “He’s a very good general.” And Napoleon said, “I know he’s good, but is he lucky?” I’ve been haunted by this exchange. I have lost friends, I have friends around me who are desperately ill, and I have survived my wife by some 25, 26 years, and you don’t know why you’re lucky. That’s the thing about luck. It’s a mysterious thing. Everything ends the same way; it just hasn’t ended that way yet for me. So, I try to enjoy every single breath I take. And I’m very conscious of the fact that I’m being allowed to take it.

AL: You mention how troubled you are by world events, and in the past, you’ve taken on troubling topics—The Day After springs immediately to mind. Is this the most troubled you’ve ever been?

NM: Absolutely. I think our country is in greater danger than any time since the Civil War. I am frightened that this man, who somebody referred to as the “Shakespeare of Shit,” simply destroys everything he comes near. And I think he has succeeded in dividing and conquering, polarizing the electorate, so we’re all at each other’s throats. And I tremble. I grew up loving this country. I became an autodidact about the American revolution. George Washington remains my hero. It began when I was very young with my father telling me stories about the Revolution and I thought, “This is the greatest thing I’ve ever heard—a nation founded by a bunch of philosophers who are trying to start anew.” It’s still amazing to me: One piece of paper holding the whole rickety thing together. Amazing. And yet, as we have forfeited our cultural memory to such an extent that we no longer know or care who we are or what we stand for, we have abandoned ourselves, we have allowed education to wither on the vine. We have forfeited the whole notion of education, and a democracy depends on education. So I’m terrified, yes.

NM: Do you have a fallback plan?

AL: Uruguay.

NM: Really, why?

How do you know when you’re living through history? How did some people in Germany know it was time to get out?AL: Well, I hear it’s the best place and the name of its capital can’t be said without being happy; Just say the name: Montevideo. It just sounds happy when you say it. I was there about two years ago. My girlfriend and I went to Argentina, and took the high-speed ferry there, and I thought, worst-case, I’ll come here. I didn’t want to leave America during the Vietnam War, I didn’t want to go to Canada; I stayed and toughed it out with the draft board and got a medical discharge. But I didn’t want to abandon my country. This is different. And one question haunts me: How do you know when you’re living through history? How did some people in Germany know it was time to get out? How do you know when it’s time to go to Uruguay? Or, in the words of Huck Finn, how do you know when it’s time to “light out for the territories?” How do you know?

NM: Can Sherlock Holmes solve our predicament? Are you done with him? Or are there other things out there you’d like him to confront?

NM: It’s weird that you say that because someone just gave me an idea for a milieu where Holmes could function and I thought, “Gee, that sounds kind of cool; that sounds like something that hasn’t been done.” So I’ve been mulling. I haven’t lifted a finger to do any research yet, but if Protocols becomes a success, I may have to scratch that itch again.

AL: Don’t wait 26 years for this one.

NM: I don’t think I can.