Humankind is predisposed to the hyperbolic. It was a true in the Titanic’s day as it is today. We love anything that smells of success. We want it huge, we crave it grand: the biggest, the fastest, the most opulent, the richest. We are drawn to such claims like moths to flame.

As much as we love hyperbole, however, it invariably leads to disappointment. This world is not meant for absolutes. Every title has an asterisk or footnote, explaining why any claims must be qualified. The problem is that we love our absolutes and have no patience for the fine print.

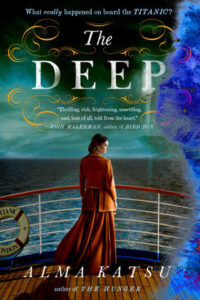

It is no mystery why we’re drawn to the Titanic. In writing my novel The Deep, a reimagining of the sinking of RMS Titanic and its sister ship, HMHS Britannic, I studied the events surrounding two ships in painstaking detail. While these events provide a wealth of things to capture the imagination—the glamorous passengers, the political and social moment in time—it was the parallel between those events and the current day that I found most striking. As The Deep explores, it was an age in which women faced considerable oppression and little legal recourse to improve their situation. It was also a time of great economic disparity: the rich were getting obscenely richer thanks to improvements in manufacturing and trade, while the lower classes sank further into poverty. Colossal tragedy was right around the corner: the Spanish Flu epidemic was a few years off, as was the Great War. There was a sense of giddy optimism but, at the same time, a creeping realization that maybe we were only pretending that things were great.

RMS Titanic captured the popular imagination when it was launched in late March 1912. It was born into grandeur, the largest passenger ship of its day (though, given the arms race among the world’s shipbuilders, it would be eclipsed by the SS Imperator less than a year later). A key selling point was safety. Passengers were right to worry: sinkings were more common than airplane crashes are today. A White Star vice-president went so far as to claim the ship was unsinkable. As boasts go, it was clever: every day the ship doesn’t sink, you look like a genius. Too bad for White Star Lines, the ship sank on the fourth day of the voyage.

This ridiculous boast made the Titanic forever synonymous with hubris. The ship’s funnel tops sank under the waves in three hours once it struck the iceberg. Common sense would tell you that no ship is unsinkable, and certainly not one weighing over 50,000 tons. Imagine if modern airplane manufacturers promised that a particular model of aircraft would never fall out of the sky. Yet much of the public chose to embrace this threadbare claim.

Did White Star Lines suffer any consequences for its bald-faced lying? J. Bruce Ismay, CEO of White Star Lines, was a passenger aboard the Titanic for its maiden voyage. Ismay managed to escape on one of the lifeboats, though he was widely criticized for his cowardice. Still, he managed to live with this shame to a ripe old age, something you can’t say about John Jacob Astor, the richest man in America, or the other 1,500 people who drowned in the freezing cold Atlantic waters.

As the Titanic goes to show, it is easy for humans to cling to denial when faced with existential threats like spiraling poverty and consolidation of power by elites. How does one prepare for doomsday? Is it so unexpected that many would prefer to believe the lies and would refuse to see the iceberg until chunks of it came crashing onto the deck?

In real life, Titanic’s sinking provided a wake-up call. A review of the incident informed industry-wide improvements in both design and safety procedures. The launch of Britannic, the last ship in the line, was delayed so that improvements could be made to the hull design, changes that probably accounted for the far lower loss of life when the Britannic, now a hospital ship, struck a sea mine and sank on November 21, 1916 (approximately 1500 people were killed when the Titanic sank, only 30 on the Britannic).

What lessons can we take away from the sinking of the Titanic? It reminds us that massive self-deception can’t be sustained, that after every disaster there’s going to be a reckoning, an attempt to set things right. I think that’s one reason so many people remain fascinated with the Titanic: because even though we know its sad ending, we know that come the dawn, there’s going to be a rescue ship on the horizon.

*